Thomas Hope’s Sculpture Galleries

Thomas Hope: An Overview

Thomas Hope (1769-1831) was born in Amsterdam, into a Dutch family of Scottish origins, who were the proprietors of Hope and Company—one of the most prosperous merchant banks of the era. In 1794, as French forces advanced on Holland, the impending political upheaval prompted the family to relocate to London, at that time the “largest and richest city in the world,” where they would continue their high-profile activities as distinguished collectors and patrons of the arts.1 In short order, Thomas Hope would become a celebrated designer, collector and writer of the Regency period in Britain.

London.

(Wikimedia Commons)

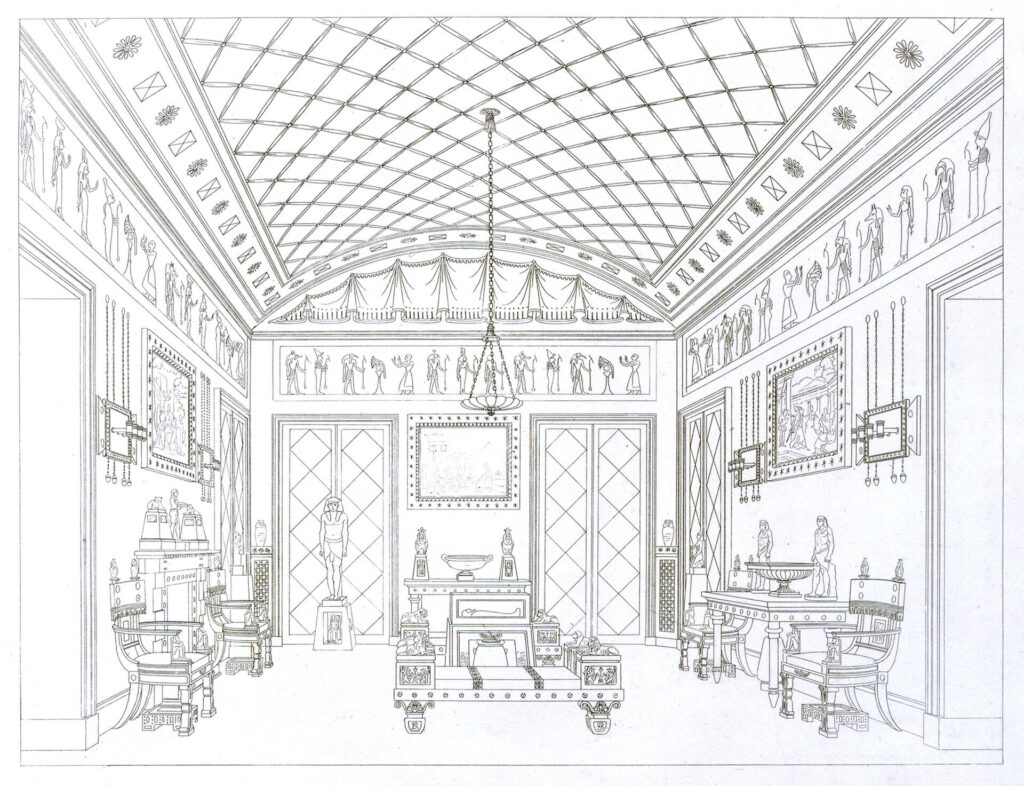

Hope travelled extensively in the 1790s, in Italy, Spain, Portugal, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, which formed his passionately neoclassical tastes and his interest in other cultures and civilizations, both past and present. He settled in London in 1798, purchasing (in 1799) the mansion in Duchess Street that would provide the setting and stage for his activities as an influential collector, and a gifted designer of furniture.2 Hope, who is responsible for first using the phrase “interior decoration,” published a book extolling the principles of design that informed many elements of the remodelled house, which featured reception rooms in a neoclassical style alongside themed spaces such as the Indian Room and the Egyptian Room, where decorative ornaments derived from papyrus scrolls and mummy cases supplied an imaginatively appropriate setting for the display of his collection of Egyptian antiquities.

In addition to writing extensively on architecture and design with the aim of reforming public taste, Hope published a well-received novel, Anastasius (1819), inspired by his early travels, that stoked interest in the Islamic world; two illustrated volumes on Costumes of the Ancients (1809) and Designs of Modern Costume (1812); and a proto-Darwinian philosophical treatise, An Essay on the Origin and Prospects of Man (1831).

Hope was, like many of his contemporaries—some of whom also created museum-like spaces in their homes—an avid collector of Old Master, classical, and contemporary artworks. David Watkin has claimed that Hope’s collection, which he accumulated mainly in Italy in the Napoleonic era, c.1795-1803, was second only to William Beckford’s, and “one of the most important and influential ever assembled in Britain.”3 His collections of classical sculpture included many distinguished, original works—some twenty six figures or groups, as well as busts (such as Lucius Verus and Faustina the Elder, both currently in the Royal Ontario Museum), heads, torsos, cineraria, and candelabrum. Among the most prized large figures were the Hygeia and the Athena (both second-century Roman recreations of lost Greek originals), an Apollo and a “finely modelled sculpture of Antinous” found at Hadrian’s villa, and a well-preserved Aphrodite in a similar pose to the famous Venus Medici.4

Hope purchased his sculptures through dealers, either from existing collections in Rome (these sculptures were generally restored, or re-restored), or directly from excavations then underway.5 In addition to his substantial investment in antiquities, Hope commissioned important new works from prominent contemporary sculptors, such as John Flaxman, Antonio Canova, and Bertel Thorvaldsen, who created a portrait bust of Hope (in 1816-17), and a large statue of Jason with the Golden Fleece (a commission begun in 1802 but not completed until 1828).

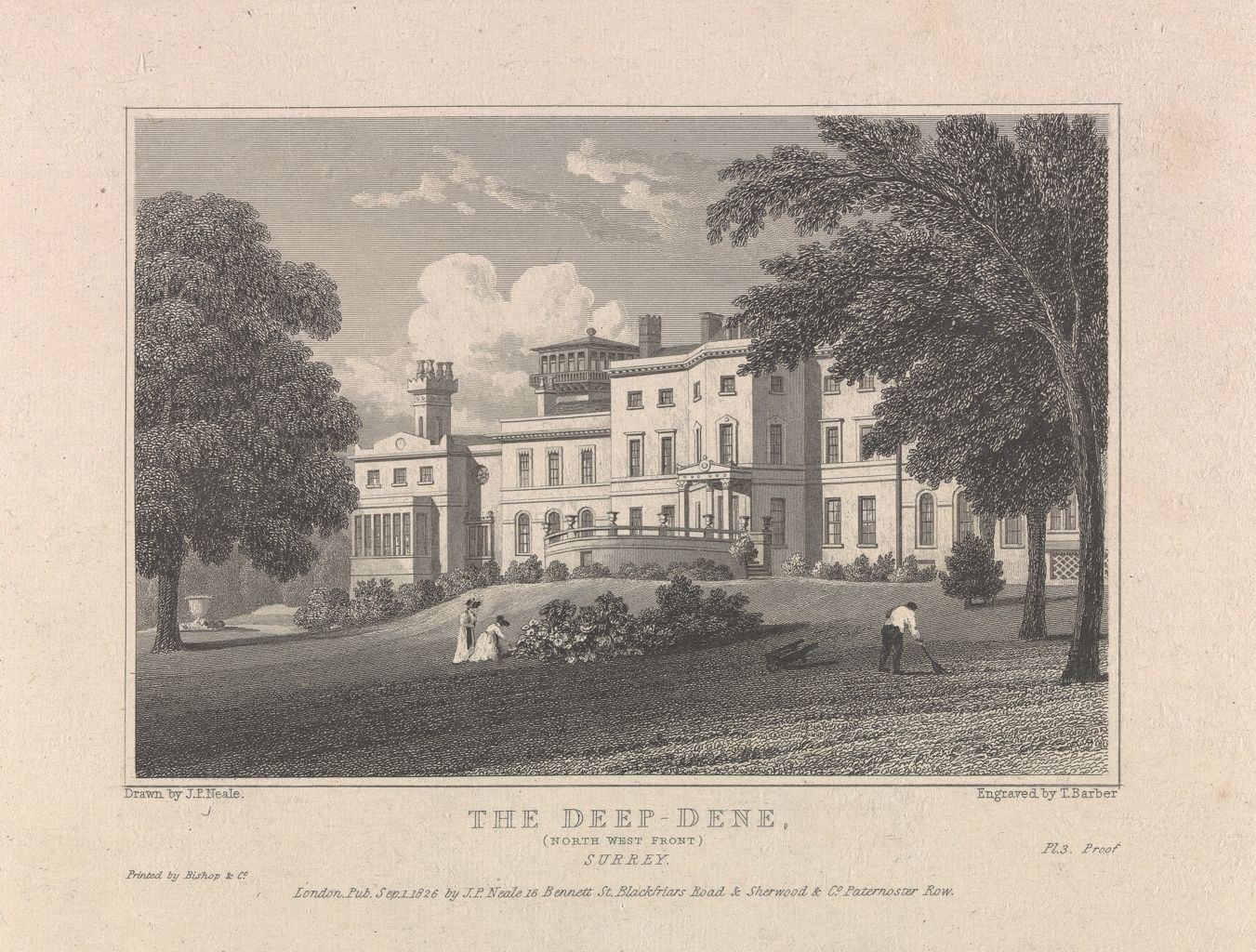

While Hope’s growing sculpture collection occupied pride of place in the arrangements at Duchess Street, many would be relocated (and others added) to Hope’s country house at Deepdene, which he purchased in 1807. The house, in a picturesque rural setting near Dorking, Surrey, was also substantially enlarged, redecorated, and furnished in accordance with Hope’s aesthetic priorities. After Hope’s death in 1831, his collections were preserved at Deepdene, where they remained through much of the nineteenth century, until they were sold at auction in 1917.

Duchess Street, London

Hope’s house in London’s Duchess Street, which he purchased from Lady Warwick, the sister of Sir William Hamilton, had been built by the fashionable architect Robert Adam in the late-eighteenth century. Hope’s extensive alterations, largely complete by 1801, involved the creation of a suite of reception rooms and museum-like gallery spaces on the first floor that (from 1804) were open to the public. Like Horace Walpole at Strawberry Hill, Hope issued admission tickets and compiled a descriptive catalogue of the house and its contents.

by Thomas Hope (1807).

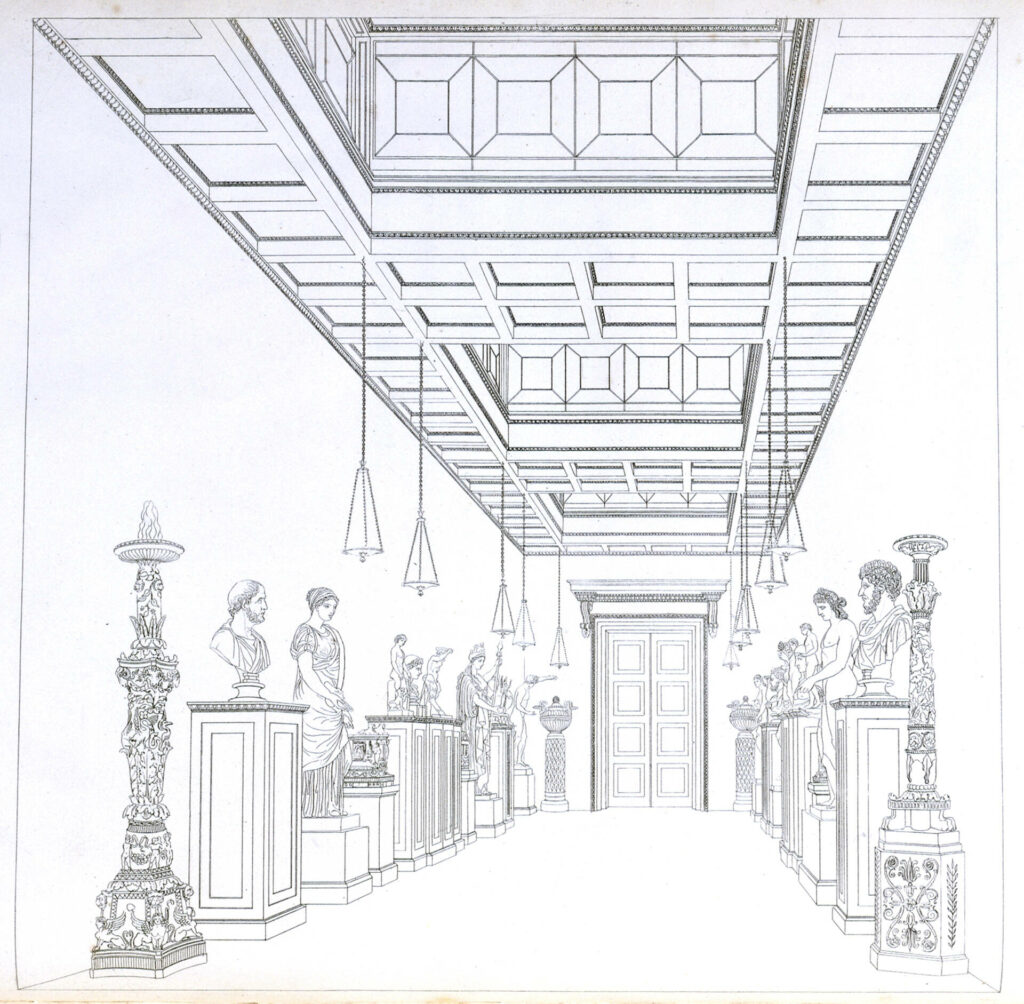

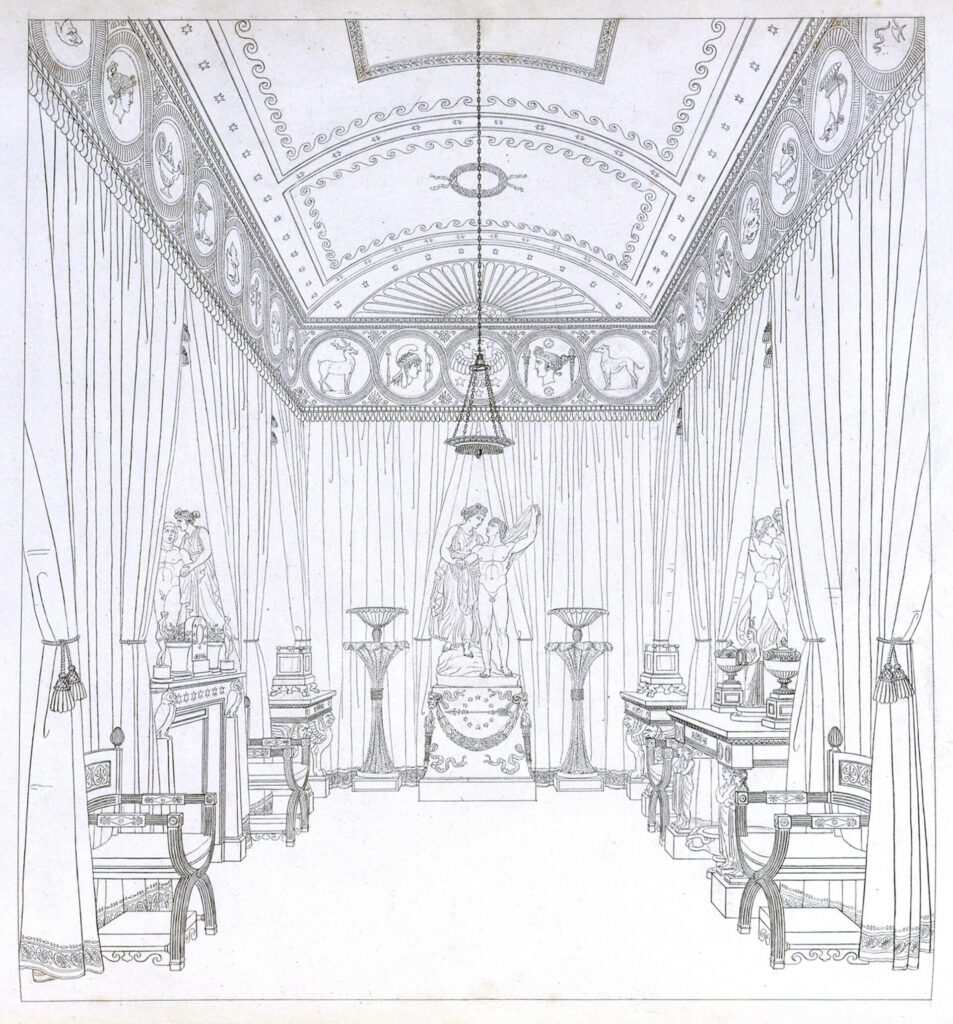

Visitors followed a prescribed route that began in the ‘staircase-hall’ on the ground floor, where they were greeted by William Beechey’s imposing portrait, Thomas Hope in Turkish Dress, which set the tone by signaling Hope’s cross-cultural outlook, and his Oriental as well as Greek Revival tastes. From there, they ascended to the first floor and into the Sculpture Gallery, where many of his classical statues were displayed to enhanced effect against deliberately plain walls, painted yellow (the Hygieia and the Athena are both visible on the left). The coffered ceiling, in imitation of a Greek temple, contained three openings for the entry of light. As Hope’s illustration shows, sculptures line the walls of the narrow gallery in symmetrical ways, with similar objects—whether full size statues, urns, or portrait busts such as those of Lucius Verus (see Featured Sculptures) and Antoninus Pius—facing each other. Further statues could be found in the next room, the Picture Gallery, which was also modelled on features of a Greek temple, referencing the “first musaea, or repositories of the Muses” extolled by Hope as “nurseries … of modern art.”6 After this, the visitor took in a sequence of three dedicated vase rooms containing more than 500 examples, many acquired from the extensive collections of William Hamilton, before entering the Indian Room (the main drawing room, also known as the Blue Room), the Flaxman Room, the Egyptian Room, and Dining Room.7

Hope’s treatise, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration Executed from Designs by Thomas Hope (published in 1807), showcased the house and the principles by which Hope went about its transformation. Hope included many of his own illustrations, which are one of the main sources of information we have, along with the accounts of visitors, about what he achieved. These line engravings, however, are flat and austere, and do not convey the extent to which what Hope created was a lush theatre for the senses, along the lines of the ‘union of the arts’ exemplified by the architect and collector Sir John Soane at his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Hope’s rooms, in their design and furnishings (which were costly, splendid, and often fanciful), were carefully contrived to provide appropriate settings for the objects they contained—they made judicious use of colour and, occasionally, sound and scent. The Flaxman Room (or Star Room) is a good example. It was designed entirely around a sculptural group Hope commissioned from Flaxman in the early 1790s, Aurora Abducting Cephalus at Dawn on Mount Ida. The colours, draperies, furnishings, and accessories in the room were all carefully dictated by an iconographic and aesthetic program responsive to the narrative elements, drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, embodied in the sculptures; these included the use of mirrored panels on the walls, and satin curtains—as Hope explained—“of the fiery hue which fringes the clouds just before sunrise” under a ceiling of “cooler sky blue.” 8

Hope’s last major alteration to the house was the addition, in 1819, of the Flemish Picture Gallery to house a large collection of paintings inherited by his brother. By then, however, much of his energy was taken up by renovations at his country house in Surrey, Deepdene. After his death in 1831, Hope’s London house passed into the hands of his eldest son, Henry, who later sold it; Hope’s collections were transferred to Deepdene before it was demolished in 1851.

The Deepdene, Surrey

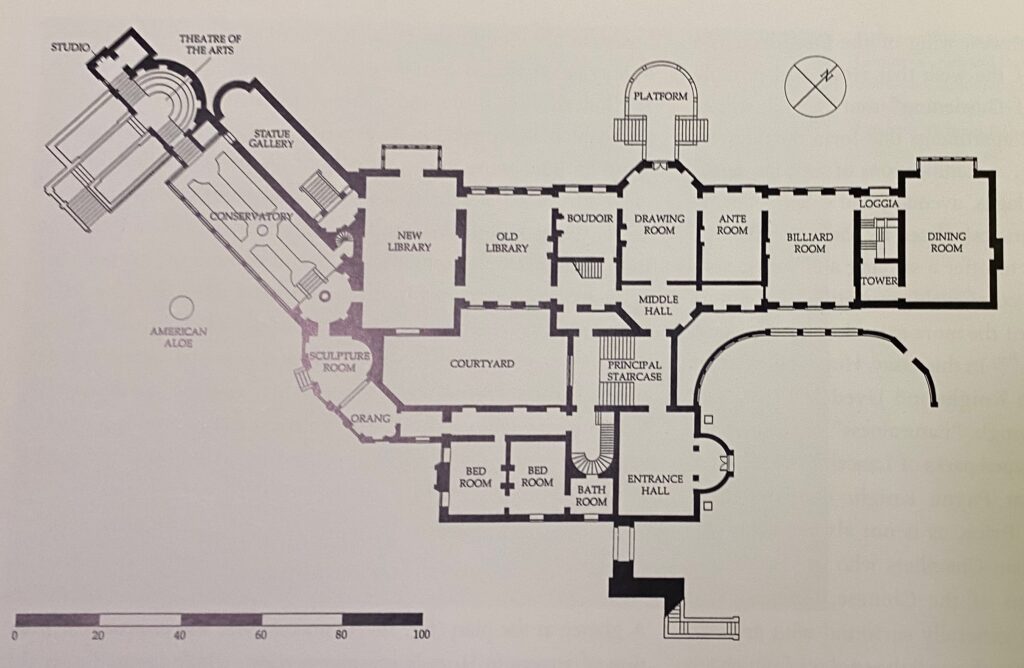

Originally a Palladian style two-story brick mansion, Deepdene was extensively remodelled by Hope (particularly between 1818 and 1826)—and like Duchess Street, it would stand as an exemplary artistic achievement. His eclectic alterations, executed by the architect William Atkinson, included the addition of an Italianate tower, a loggia (in Pompeiian style), and a variety of interventions that introduced asymmetry into the relationship between the house and gardens in keeping with the aesthetics of variety and irregularity favoured by the picturesque. John Britton’s unpublished “History of the Deepdene” (1821-26), which was to be illustrated by watercolours painted by Penry Williams and William Henry Bartlett, emphasizes its connection to the picturesque in its subtitle: “The Union of the Picturesque in Scenery and Architecture with Domestic Beauties.” A substantial portion of Hope’s classical sculpture collection was moved to Deepdene from London in 1824-5, where, by contrast to Duchess Street and to the example of other collectors such as Charles Townley, sculpture was an integral part of a picturesque programme inviting the outdoors in (and vice versa).9

Chief among Hope’s alterations to the house was the addition of a whole new wing, extending southwestward at a 45-degree angle from the main house. The new wing included four different galleries for the display of sculpture. Two of the larger spaces, the Statue Gallery and the Theatre of the Arts, were intended for antique statues and artifacts, while two smaller ones contained neoclassical sculptures and modern copies.10 All were connected in some way by the Conservatory, with its lush greenery and fountain, at one end of which was the domed apse featuring Thorvaldsen’s Psyche in a mirror-backed niche approached up a flight of stairs (see Featured Sculptures). In Williams’s watercolour, the door on the left leads to the library; on the right, into a room described by Hope as the “Orangery and Sculpture Gallery” that housed Thorvaldsen’s Jason and a copy of the Florentine Boar. The fourth and final gallery was the small ‘studio’ off the far end of the Theatre of the Arts, in which could be found some minor antique pieces and another work by Thorvaldsen, A Genio Lumen.

The Statue Gallery was in some respects like the one in Duchess Street, if less austere, with buff walls and round-headed clerestory windows providing ample top-lighting.11 Statues, busts, and candelabra lined the walls. In the watercolour, Aphrodite is prominently visible on the left; large busts of Roma and Jupiter face each other, as do Apollino and the Aphrodite Medici (far left and right). Evident here, however, is a more playful mix of ancient and modern statues, family busts, and thematic references to “love, woodland, and death.”12 In the centre, is an ornate child’s sarcophagus (a copy of one in the Vatican), possibly in memory of Hope’s son Charles who had died young in Rome. At each end of the gallery is a circular apse, and presiding from a pedestal at the far end, as we see in Williams’s illustration, is a statue of Silenus (see Featured Sculptures), the “Greek god of flocks and shepherds.”13

In spite of its more rural location, Deepdene was a hub of social activity, welcoming numerous visitors, including “leading intellectuals and artists of the Regency period” and royalty, such as the Duke and Duchess of Clarence (later King William IV and Queen Adelaide).14 After Hope died in 1831, Deepdene also passed to his son Henry Hope who turned it into a full-blown “Italianate Renaissance villa,” and removed the more rambling, irregular features—the “mold-breaking and fragmentary work”—that had made it architecturally unique.15 Much of the sculpture was relocated to a grand entrance hall, also top-lit, and displayed in the arches of the two-story arcade. The house was unfortunately demolished in 1969, and what remains of Thomas Hope’s Deepdene is now a public park, with its own app, enabling visitors to explore the landscape and history of the estate, highlights of which are the Hope family mausoleum, the grotto, and a “romantic tower.”

The Theatre of the Arts

The “Theatre of the Arts” was the most unusual of Hope’s new galleries for the display of ancient sculpture. Its semi-circular structure, forming a half dome facing the gardens, directly imitated ancient Greek and Roman theatres. In place of spectators, however, we find statues, busts and cinerary urns occupying the ‘seats,’ regarding the visitor who—passing through perhaps from the terrace to the small temple at one end, or to the conservatory leading back towards the main house and the more formal sculpture gallery beyond—momentarily occupies the ‘stage.’ This central, if transitional, viewpoint (just inside the doors such that one may swivel between the gallery and garden) is captured by our 3-D recreation of the gallery.

Facing the viewer in the Theatre of the Arts were three ascending tiers of artifacts, all arranged symmetrically according to such features such as size, gender, type and subject. In the first were a variety of cinerary urns and vases, with a head at each end, including the beautiful semi-circular cinerarium decorated with garlands and rams’ heads (visible second from the right in Williams’s watercolour) and an unusual cinerary basket on a plinth, supporting a herm (two more over to the left). The second was given to busts of (among others) Dionysus, Faustina the Elder, Agrippina, Septimius Severus, and Lucius Verus. Five niches in the back wall along the top housed full-sized sculptures of Aphrodite, a Bacchante, Apollo, Venus Marina, and Peplophorus (see Featured Sculptures for further details of a selection of these). The exterior wall, or façade, of the Theatre, though appearing relatively plain on the inside, contained other unusual architectural features such as the striking, triangular-headed doors and windows, “half-way between Gothic and Tudor.”16 A colourful hanging lamp in the shape of a lotus, likely made of glass, hung over the entrance. Waywell notes that a marble tripod, not represented in Williams’s watercolour, was placed in the middle of the tile floor, which was made up in part of mosaic from Hadrian’s Villa. What John Morley, in his study of Regency design, describes as “polychromatic Chinese porcelain garden seats” are prominently visible on the steps.17

With its orientation towards the outdoors, either through the adjacent conservatory or out through the principal doors into the gardens and surrounding countryside, the Theatre of the Arts is perfectly integrated into Hope’s picturesque vision for Deepdene. In an essay “On the Art of Gardening” that Hope wrote in 1808, he proposes that to attain the qualities of contrast, variety and “brokenness of levels” central to the theory of the picturesque (in the work for example of Uvedale Price and William Gilpin), “we can only seek it in arcades and in terraces, in steps, balustrades, regular slopes, parapets.”18 The house as Hope re-imagined it contained “the same sudden contrasts of height, level, shape, and style as the garden, and moves with astonishing versatility from Gothic to Classic, from Greek to Italian, from a style combining elements of both to another style of such originality, notably that of the exterior of the Theatre of the Arts, that it can be pinned down to neither.”19 It is in this spirit that the garden and the house infiltrate and inform each other, evident in such spaces as the Psyche niche at the end of the Conservatory, as much as in the experience of the visitor leaving the south-west wing through the Theatre of the Arts, descending into the sloping ground beyond via terraces and steps, with ornate vases perched on pedestals.

Appropriately, the name of Hope’s country house also describes its physical location: a “dene,” as Maria Edgeworth noted, is a Saxon word meaning “a deep rift in a wood—in short a deep dingle.”20 Intriguingly, and by happy coincidence, a “hope” is also a feature in the landscape—a long valley or natural bowl. In descriptions of the estate from the seventeenth century, under the ownership of Charles Howard, Aubrey’s Antiquities of Surrey remarks on how “he hath cast this Hope into the form of a Theatre, on the side whereof he hath made several narrow walks, like the seats of a theatre” that were bordered with lush vegetation, creating a fittingly Italianate, picturesque retreat.21 When Hope bought the estate, the sale catalogue described the accompanying 100 acres of ground as containing “luxurious forest trees … walks, rural retirements, grottoes, cavern, terrace…”22 With this in mind, we can appreciate how the novelty of the Theatre of the Arts derives in many nuanced ways from its immediate physical surroundings, including Hope’s own “amphitheatrical” hill, upon which he constructed a “vaguely Etruscan temple.”23

Hope in Context

Hope’s creation of galleries and museum-esque spaces in his homes in London and at Deepdene, while highly imaginative, was not entirely unique. The display of sculpture, in spaces such as entrance halls and dedicated galleries, had become a prominent feature of the British country house, for example at Newby Hall, Wentworth Woodhouse, Petworth, Wilton House, or Chatsworth. In these contexts, the collection and display of classical sculpture (including casts and copies) spoke for the cultural acumen, and wealth, of their aristocratic owners. Closer to home, so to speak, for Hope, was the example of Charles Townley who (in addition to planning a dedicated Sculpture Rotunda at his Lancashire seat) used his house at Park Street in London to showcase his extensive collection of antiquities. In such spaces as the Entrance Hall and Dining Room, the sculptures were the central focus, forming a personal if scholarly museum, rather than serving a secondary or decorative function.

The watercolour by William Chambers depicts the interior of the dining room as it appeared in 1794. As Viccy Coltman observes, the colour scheme of the dining room, with its “blue background against the porphyry-coloured Ionic columns in scagliola,” was chosen to heighten the monochromatic whiteness of the marble sculptures and reliefs.24 While many statues line the walls in more formal arrangements, such as the “Townley Venus” (on the right, excavated at Ostia, near Rome), others, such as the prized Discobolus, occupy prominent positions at the centre. Townley staged deliberate dialogues between his sculptures, juxtaposing or grouping them in contrast, and the athletic Discobolus is a great example, flanked as it is by two reclining statues—Endymion on the left, and a drunken faun on the right.

When Townley died in 1805, his collections were transferred to the British Museum, where they formed the nucleus of a department devoted to Greek and Roman antiquities that would soon be revolutionized by the arrival of the Parthenon marbles in 1816. House-museum collections of the early nineteenth century, such as those of Thomas Hope and John Soane, drew from some aspects of what Townley exemplified. Both attentively read the work of Townley’s intellectual collaborator, the self-styled Baron d’Hancarville, and in particular his systematic study of Greek art. But by the turn of the nineteenth century, as Ruth Guilding notes, “the political resonances associated with classical sculpture had begun to be eroded and replaced by more romantic or idiosyncratic personal constructs.”25

The London house of the architect Sir John Soane, in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, was home to his extensive collections—mainly classical and antiquarian in orientation—of antiquities, sculpture, architectural fragments, models and casts, paintings, books, and curiosities such as the alabaster sarcophagus of Pharaoh Seti I housed in the ‘Sepulchral Crypt’ downstairs. In addition to functioning as the studio of a professional architect (and resource for students), the house reflected Soane’s historical and aesthetic preoccupations. His arrangements were dramatic, predicated on imaginative associations and juxtapositions, and on the judicious use of light, mirrors, and coloured glass. Carefully staged and varying viewpoints, as John Britton observed, surprise, fascinate and delight as the visitor moves through a succession of interior spaces that deftly bring the picturesque indoors.26 While collection items were dispersed throughout the house, much of the sculpture was housed in the domed colonnade at the rear, where we find a dense assemblage of architectural and sculptural casts and fragments, many of them antique, along with the work of contemporaries such as Flaxman. Here, too, are models and full-sized statues such as the copies of Hercules and Diana, as well as many vases and urns. Opposite the prominent cast of the Apollo Belvedere, Francis Chantrey’s marble bust of Soane himself, flanked by Flaxman’s statuettes of Michelangelo and Raphael, presides over the whole.

Other contemporaries of Hope’s who created personal and often theatrical domestic interiors for the display of their collections—also inspired by such eighteenth-century figures as Horace Walpole, who fabricated a “little gothic castle” at Strawberry Hill—include William Beckford. At Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire, built in gothic revival style, Beckford created extravagant and opulent interiors to showcase his rich collections of artworks and objets d’art. Here, too, visual effects and vistas were carefully created, such as by the three-hundred-foot-long corridor running from St Michael’s Gallery at one end of the house to the Oratory at the other, where his prized statue of St. Anthony was dramatically situated.27 Interesting connections between Hope, Soane and Beckford have been explored by David Watkin, who observes in all three the flowering of a new sensibility: while none of them was of aristocratic origins, all “inherited commercial wealth in the 1780s, enabling them to indulge their visual passions by collecting and by creating personal settings of immense aesthetic individuality.”28 Intriguingly, a figure who unites them all is John Britton, engaged by each to write descriptive accounts of their singular creations. Sadly, Britton’s description of Deepdene, for which the watercolour illustrations by Williams and Bartlett were created, was never published.

Notes

- Philip Mansel, “European Wealth, Ottoman Travel, and London Fame” in Thomas Hope: Regency Designer, edited by David Watkin and Philip Hewat-Jaboor (Yale University Press [for] The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture, New York, 2008), 7.

↩︎ - Some excellent examples of these items are now in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. See https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/thomas-hope-and-the-regency-style

↩︎ - David Watkin, “Beckford, Soane, and Hope: The Psychology of the Collector” in William Beckford, 1760-1844: An Eye for the Magnificent, edited by Derek E. Ostergard (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2001), 39. The comprehensive exhibition catalogue, Thomas Hope: Regency Designer, includes chapters specifically focussed on the collections of sculpture and painting, Hope’s furniture, his impact on fashion, as well as his extensive writings.

↩︎ - David Watkin, Thomas Hope 1769-1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea (London: John Murray, 1968), 48.

↩︎ - See Geoffrey B. Waywell, The Lever and Hope Sculptures (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1986), 40. Waywell notes that these would also have been “cleaned and restored before being exported” (40). See Waywell, 40-42, for a detailed account of the collection’s origins. See also Ian Jenkins, “The Past as a Foreign Country: Thomas Hope’s Collection of Antiquities” in Watkin and Hewat-Jaboor, ed., Thomas Hope: Regency Designer, 107-129.

↩︎ - Cited in David Watkin, Thomas Hope 1769-1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea, 104.

↩︎ - See the detailed description of these rooms in Watkin, Thomas Hope 1769-1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea, chapter 4.

↩︎ - Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration Executed from Designs by Thomas Hope (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, & Orme, 1807), 25.

↩︎ - Exactly which statues were moved, and which left, is explained/enumerated by Waywell (50).

↩︎ - David Watkin, “The Reform of Taste in the Country: The Deepdene,” in Watkin and Hewat-Jaboor, ed., Thomas Hope: Regency Designer, 225.

↩︎ - Watkin, “The Reform of Taste,” 226.

↩︎ - Watkin, “The Reform of Taste,” 226.

↩︎ - Watkin, “The Reform of Taste,” 227.

↩︎ - Waywell, 37.

↩︎ - See Watkin, “The Reform of Taste,” 231, 233.

↩︎ - Waywell, 54.

↩︎ - John Morley, Regency Design, 1790-1840: Gardens, Buildings, Interiors, Furniture (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1993), 287.

↩︎ - Watkin, “The Reform of Taste,” 225.

↩︎ - Watkin, “The Reform of Taste,” 225.

↩︎ - Maria Edgeworth, Letters from England, 1813-44, ed. Christina Colvin (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), 193.

↩︎ - Cited in Watkin, Thomas Hope 1769-1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea, 159-60.

↩︎ - Watkin, Thomas Hope 1769-1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea, 161.

↩︎ - Watkin, Thomas Hope 1769-1831 and the Neo-Classical Idea, 163.

↩︎ - Viccy Coltman, Classical Sculpture and the Culture of Collecting in Britain Since 1760 (Oxford UP, 2009), 214.

↩︎ - Ruth Guilding, Marble Mania: Sculpture Galleries in England 1640-1840 (London: Sir John Soane’s Museum, 2001), 13-14.

↩︎ - John Britton, Union of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting; Exemplified by a Series of Illustrations, with Descriptive Accounts of the House and Galleries of John Soane (London, 1827), 13.

↩︎ - For a comprehensive, illustrated account of Beckford’s connection to this statue, see https://edizionicafoscari.unive.it/media/pdf/article/mdccc-1800/2021/1/art-10.30687-MDCCC-2280-8841-2021-10-007.pdf

↩︎ - David Watkin, “Beckford, Soane, and Hope: The Psychology of the Collector” in William Beckford, 1760-1844: An Eye for the Magnificent, 34.

↩︎