Lesbian and Gay Liberation in the Late 1970s / Early 1980s

by Craig Jennex

The 1970s were formative years for lesbian and gay liberation organizing in Toronto, the province of Ontario, and Canada more broadly. During this decade, activists formed political collectives conceived in relation to lesbian and gay identity, built coalitions with other marginalized communities, and worked to form networks across provincial borders.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1968-69, passed by Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s Liberal government at the end of the 1960s, decriminalized certain homosexual acts that occurred in private between consenting adults, decriminalized the sale and possession of contraceptives, and permitted limited access to abortion under particular conditions. While these amendments are often historicized as a radical transformation of the way the Canadian government related to citizens’ experiences of gender and sexuality within Canadian society, the material effects of the changes were far less significant than one might be led to believe in our contemporary moment. Indeed, as Tom Hooper, Gary Kinsman, and Karen Pearlston write on behalf of a collective of academics and activists who challenged the 2019 federal government’s commemoration of the so-called decriminalization of homosexuality: arrests and legal charges for “indecent” acts of homosexual sex actually increased after the 1969 amendments to the Criminal Code.

Rather than being handed down from the federal government, the profound changes to Canadian society that occurred during the 1970s were instigated and fostered by increasingly organized collectives of LGBTQ2+ activists.

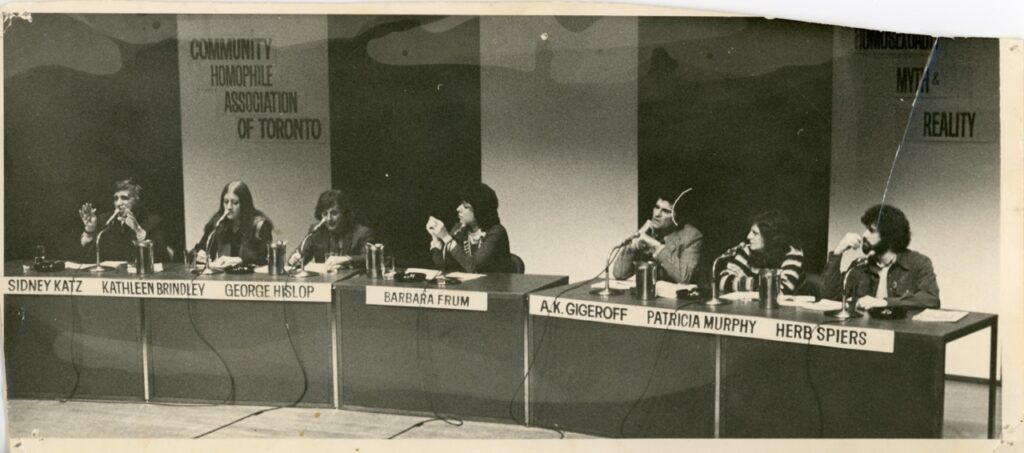

The University of Toronto Homophile Association (UTHA)—the city’s first lesbian and gay liberation organization—formed in 1969 after a chance meeting in a University of Toronto men’s bathroom that was known for gay male cruising. Soon thereafter, the Community Homophile Association of Toronto (CHAT) developed and opened a community centre at 58 Cecil Street (near College and Spadina). UTHA and CHAT both retained the “homophile” moniker that was popular with certain homosexual rights activists in the mid-20th century, but they did not ascribe to the subdued, respectful style of political activism we see in the history of homophile movements. Both the UTHA and CHAT exhibited an overt and vocal style of activism that comes to mark the lesbian and gay liberation era.

In 1971, Toronto Gay Action (TGA) collaborated with CHAT and Montreal’s Le Front de Libération des Homosexuels to organize Canada’s first large-scale lesbian and gay rights rally on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. Challenging the myth of “the homosexual problem” in Canada, protestors made a series of demands that included freedom from discrimination in housing, employment, health care, and legal status. At this rally, activists directly critiqued the aforementioned changes to the Canadian Criminal Code; speaking to reporters from the steps of the Parliament Buildings, TGA member Charlie Hill exclaimed that the amendments “did nothing to ameliorate the situation of Canadian homosexuals.” This list of demands made by activists on Parliament Hill in 1971, written by Herb Spiers and David Newcombe, served as a strategic blueprint for the Canadian lesbian and gay liberation movement in the years that followed the rally. The reaction to the rally in mainstream Canadian media showed the uphill battle these activists faced: the news director of Toronto-based CHUM Radio, for example, told listeners that “the entire Gay Liberation movement is based on the false assumption that homosexuality has some redeeming or positive aspect to it. It is negative and unproductive. It is a mental and sexual aberration.”

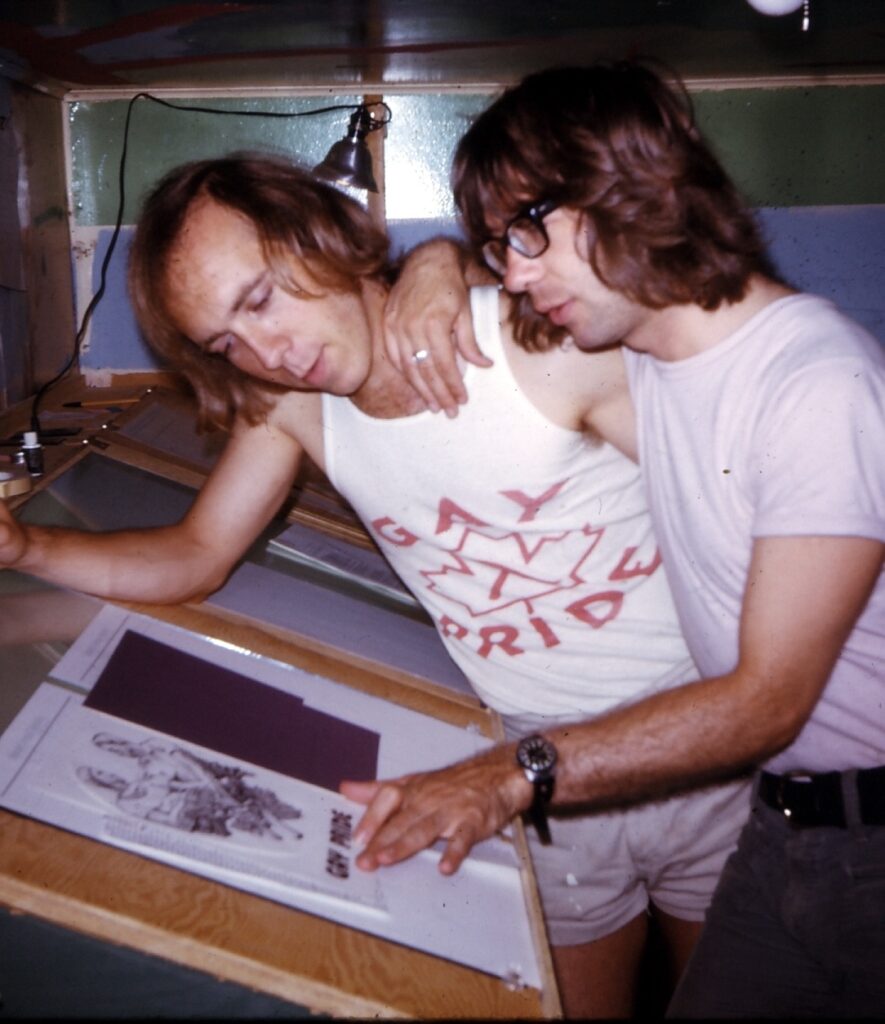

The same year as the rally on Parliament Hill, The Body Politic began publishing in Toronto. The most influential queer periodical in Canadian history, The Body Politic had a broad scope and an international audience. Indeed, The Body Politic put Toronto on the map as a primary site of lesbian and gay liberation organizing and political analysis. Later in the decade, the Gay Community Appeal (now called the Community One Foundation) began raising funds for queer community organizations and activist projects and modeled the broad, coalitional work that proved productive during the 1970s and 1980s. The Right to Privacy Committee—originally called the December 9th Defence Fund, established to respond to the December 9, 1978 police raid of The Barracks, a bathhouse in downtown Toronto—provided legal and financial assistance to gay men who faced police harassment. That same year, Rupert Raj formed the Foundation for the Advancement of Canadian Transexuals (FACT) in Calgary, Alberta—the first organization explicitly advocating for trans rights in Canada.

The 1970s also saw the development of sustained national gay and lesbian organizing in Canada. Activists from across the country met in Quebec City (1973), Winnipeg (1974), Ottawa (1975), Toronto (1976), Saskatoon (1977), Halifax (1978), and returned to Ottawa (1979) to build political movements across provincial borders. Concerns around the Toronto-centric and male-dominated nature of mainstream lesbian and gay liberation organizing resulted in smaller, regional meetings and influential lesbian-feminist conferences around the nation. These national networks of activists proved particularly important in 1978 when Anita Bryant—the conservative spokesperson for Florida orange juice—conducted a cross-Canada tour promoting her evangelical anti-gay views. By the late 1970s, organized activist networks responded to heteronormative and cisnormative political movements with vigour.

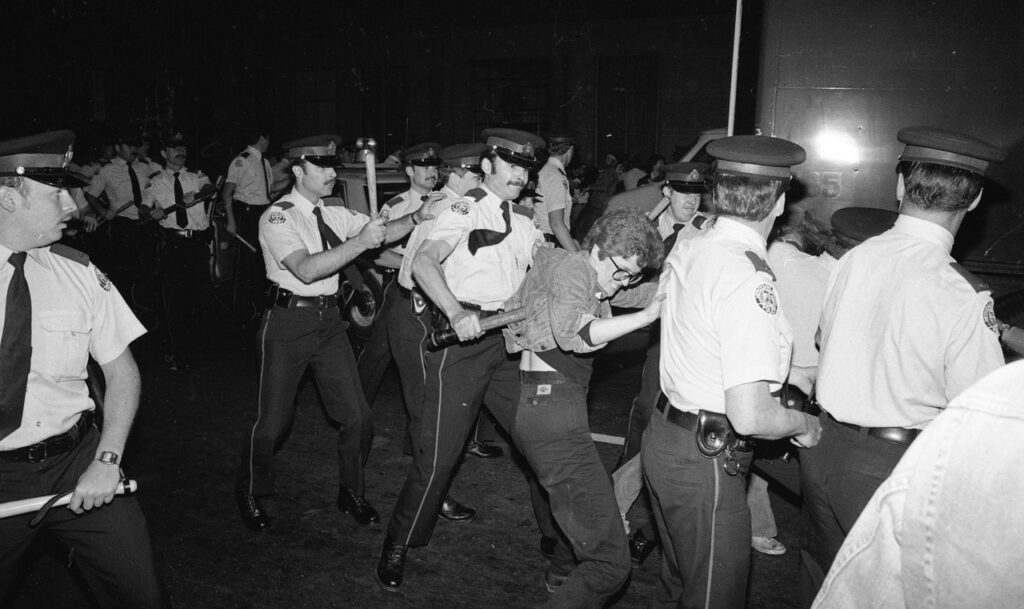

In the later half of the 1970s, and in response to victories enjoyed by lesbian and gay activists across Canada, police forces across the country began targeting spaces where LGBTQ2+ individuals convened and created communities. The most clear example of this pushback came in the form of raids of gay bathhouses in urban centres across Canada. In Toronto, for example, in February 1981, hundreds of Toronto Police Service officers, organized by the department’s Morality Squad, stormed four gay bathhouses and arrested more than 300 men (at the time, the second largest mass arrest in Canadian history second only to the FLQ crisis in Quebec and the Trudeau government’s invocation of the War Measures Act). Many men detained during the raids—which the Toronto Police Service dubbed “Operation Soap”—reported violent and excessive mistreatment by police. At The Barracks, for example, police corralled detainees into the showers, marked them with the number of the room in which they were found, forced them to strip naked, and conducted rectal searches. In a report submitted to Toronto City Council following the raids, many detainees at The Barracks recalled an officer who repeatedly expressed a desire to “annihilate” them; one man tells the Council that “I remember particularly [the officer’s] use of the word ‘annihilate’. [He said] ‘I wish these pipes were hooked up to gas so I could annihilate you all.’” The threat of violence continued long after the raids themselves concluded: Toronto Sun editor Peter Worthington, for example, repeatedly tried to publish the names of gay men charged during the raids and police reportedly contacted employers and family members of detainees in an attempt to shame them.

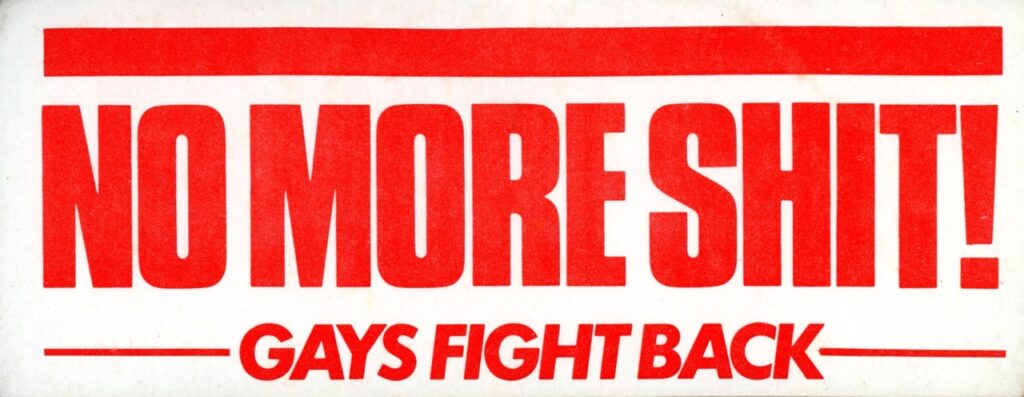

Following these raids, activism against police violence took a more urgent and aggressive tone. On February 6, 1981—less than twenty-four hours after the violent raids—Torontonians saw a spectacular transformation of the city’s downtown core. Chris Bearchell explains on Track Two, a documentary film that captures much of the immediate response to the raids, that shock resonated through the lesbian and gay liberation movement and broader leftist and progressive communities following the raids. But very quickly, she explains, shock “gave way to fury; women and men in the community went from disbelief to just rage … Rather than letting that anger weigh us down … we were able to channel it into a collective statement.” Winding through the streets of Toronto in numbers never before seen for a lesbian and gay liberation rally, activists proclaimed “enough is enough!” and “no more shit!” At the February 6, 1981 rally, Bearchell spoke to the amassed crowd: “[Police] think that when they pick on us that they’re picking on the weakest. Well, they made a mistake this time! We’re going to show them just how strong we are. They can’t get away with this shit anymore!”

In the early 1980s, activists across Canada amassed in the streets, in community centres, and elsewhere to fight anti-gay policing and politics. In this broader context, Wilde ’82 brought this battle to a seemingly unlikely space: the academy. In seeking to understand the framing and construction of homosexuality, scholars, activists, and archivists met at Ryerson Polytechnic Institute to discuss the possibilities and limitations of homosexual identity and to historicize the growing lesbian and gay liberation movement in Canada and elsewhere. This academic conference was intimately connected to the political activism taking place on city streets, legislatures, and judicial spheres. Indeed, many of the participants in Wilde ’82 were also activists who participated in and often led other forms of protest.

Further Reading:

Dryden, OmiSoore H. and Suzanne Lenon, eds. Disrupting Queer Inclusion: Canadian Homonationalisms and the Politics of Belonging. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2015.

Gentile, Patrizia, Gary Kinsman, and L. Pauline Rankin, eds. We Still Demand! Redefining Resistance in Sex and Gender Struggles. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017.

Goldie, Terry. In a Queer Country: Gay and Lesbian Studies in the Canadian Context. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.

Haritaworn, Jin, Ghaida Moussa, and Syrus Marcus Ware, with Rio Rodriguez, eds. Queering Urban Justice: Queer of Colour Formations in Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Irving, Dan and Rupert Raj, eds. Trans Activism in Canada: A Reader. Toronto: Canada Scholars Press, 2014.

Jackson, Ed and Stan Persky. Flaunting It! A Decade of Gay Journalism from The Body Politic. Toronto: Pink Triangle Press, 1982.

Jennex, Craig and Nisha Eswaran. Out North: An Archive of Queer Activism and Kinship in Canada. Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2020.

Kinsman, Gary and Patrizia Gentile. The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010.

Knegt, Peter. Queer Rights. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing, 2011.

McCaskell, Tim. Queer Progress: From Homophobia to Homonationlism. Toronto: Between the Lines Press, 2016.

McLeod, Donald W. Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada: A Selected Annotated Chronology, 1964-1975. Toronto: ECW Press and Homewood Books, 1996.

—. Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada: A Selected Annotated Chronology, 1976-1981. Toronto: Homewood Books, 2017.

Millward, Liz. Making a Scene: Lesbians and Community Across Canada, 1964-84. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2015.

Ross, Becki. The House that Jill Built: A Lesbian Nation in Formation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Warner, Tom. Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.