by Jason Boyd

Wilde ’82 was named in commemoration of the hundredth anniversary of Oscar Wilde’s 1882 visit to Toronto.

Why name a conference on gay and lesbian studies after Wilde?

By 1982, Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) was a well-established gay icon. There were numerous reasons for this status: he was known as a dandy, media personality, and wit, famous for the epigrams that peppered his West End plays Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892), A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal Husband (1895), and The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). He was also the author of the homoerotic novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), and a decadent play on a biblical figure, Salome (1893/1894), famous for her “dance of the seven veils.” But most significantly, in 1895, urged on by his lover Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde unwisely brought an action for libel against Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, who had been harassing them both, and who had left a card at Wilde’s club accusing him of “posing as a sodomite.” In response to the libel case, Queensberry had private agents collect evidence for Wilde’s “suspicious” socializing with younger, mostly working-class men, which led to Wilde dropping the libel case. The evidence Queensberry had collected was turned over to the Public Prosecutor, and, after two trials (the first one resulted in a hung jury), Wilde was charged, convicted, and imprisoned for two years with hard labour for “gross indecency” with other men. Upon his release, a pariah in England, he lived in Europe, dying in Paris in 1900. The prominence of his case and the vindictiveness with which he was prosecuted ensured Wilde’s becoming a gay hero and martyr representing society’s oppression and persecution of gay men and other sexual minorities.

Why was Oscar Wilde in Toronto in 1882?

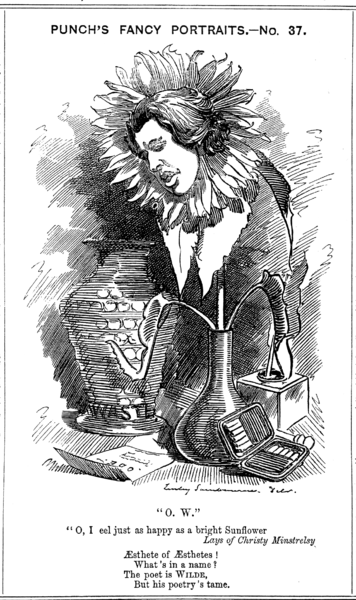

In 1882, Wilde was just starting to make a name for himself. He had had a brilliant undergraduate career at Oxford University, obtaining his degree in 1878, after which he moved to London to become a “Professor of Aesthetics.” Through self-promotion and by associating himself with prominent London artistic personalities, he ensured he was talked about (and often attacked and satirized) in the press as a leading figure of the so-called Aesthetic Movement.

After he published his Poems in 1881, the popular comic magazine Punch dubbed him the “Aesthete of Aesthetes.” When Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta, Patience, which satirized the Aesthetic Movement, was scheduled to tour North America, the producer Richard D’Oyly Carte approached Wilde and asked if he would be interested in undertaking a lecture tour at the same time. Wilde agreed and prepared lectures on ‘aesthetic’ ideas concerning artisan craftmanship and home decoration (Ellmann 151-3). Lectures were a very popular form of ‘respectable’ recreation or entertainment at the time, and other literary figures, such as the novelist Charles Dickens, had had immensely successful lecture tours in North America.

Wilde saw the lecture tour as an opportunity for fame and profit, and sailed for New York City on Christmas Eve, 1881. When he arrived in the harbour of New York on January 2nd, 1882, and was asked by a customs official if he had anything to declare, Wilde is reputed to have said: “I have nothing to declare except my genius” (Ellmann 157-60).

In Philadelphia, where he delivered his second lecture, Wilde expressed to reporters his desire to meet with Walt Whitman, whose poetry he greatly admired. Whitman responded to this desire by inviting Wilde to visit him in Camden. The two talked while sharing a bottle of homemade elderberry wine: “‘I will call you Oscar,’ said Whitman, and Wilde, laying his hand on the poet’s knee, replied, ‘I like that so much.’ To Whitman, Wilde was ‘a fine handsome youngster'” (Ellmann 168). Wilde revisited Whitman in May. Unlike the first visit, what the two discussed was not recorded, but Wilde was later to tell a friend, “The kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips” (Ellmann 171). (At the Wilde ’82 conference, Michael Lynch and Richard Partington performed a reading of Richard Howard’s poem, “Wildflowers,” a speculative imagining of Whitman and Wilde’s conversation [Howard].)

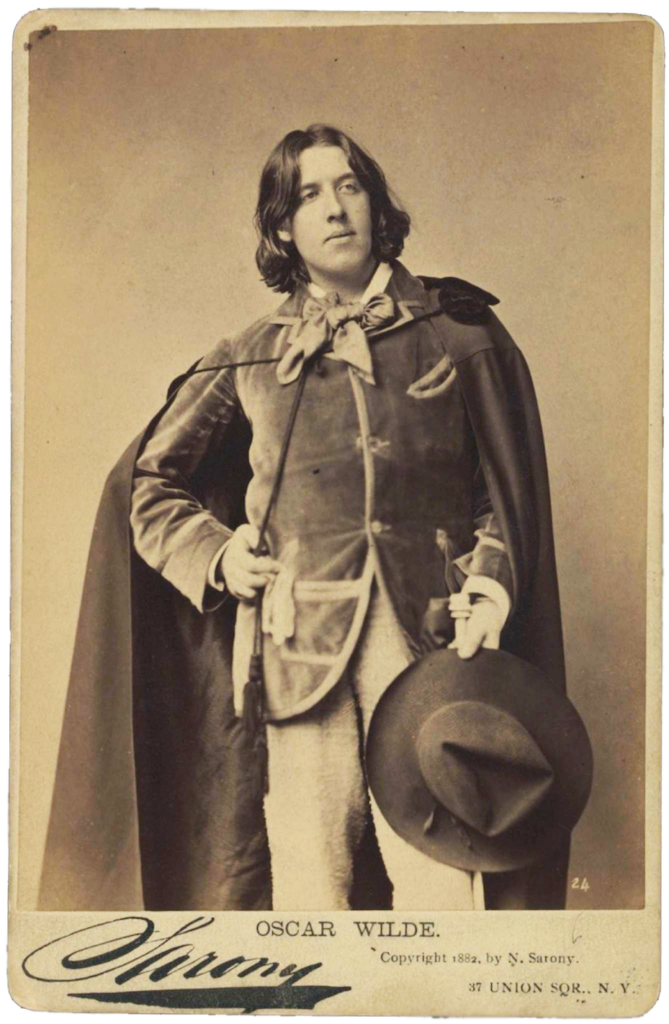

Wilde’s lecture tour in North America was extensive and included many stops in the United States and Canada (see Cooper for a full itinerary). From the day he arrived in New York, the North American press both lionized and mocked him incessantly. In New York, he made sure to get a series of photographs taken by the celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony of himself in ‘Aesthetic costume,’ which are today some of the most widely circulated and recognizable photographs of Wilde. Wilde was delighted, if a little overwhelmed, by the attention. As he wrote jokingly to a friend: “I am torn in bits by Society. Immense receptions, wonderful dinners, crowds wait for my carriage. I wave a gloved hand and an ivory cane and they cheer.” He claimed to have two secretaries: “one to write my autograph and answer the hundreds of letters that come begging for it. Another, whose hair is brown, to send locks of his own hair to the young ladies who write asking for mine; he is rapidly becoming bald” (Holland and Hart-Davis 127). Although a humorous exaggeration, Wilde indeed was treated like a celebrity during his tour of North America.

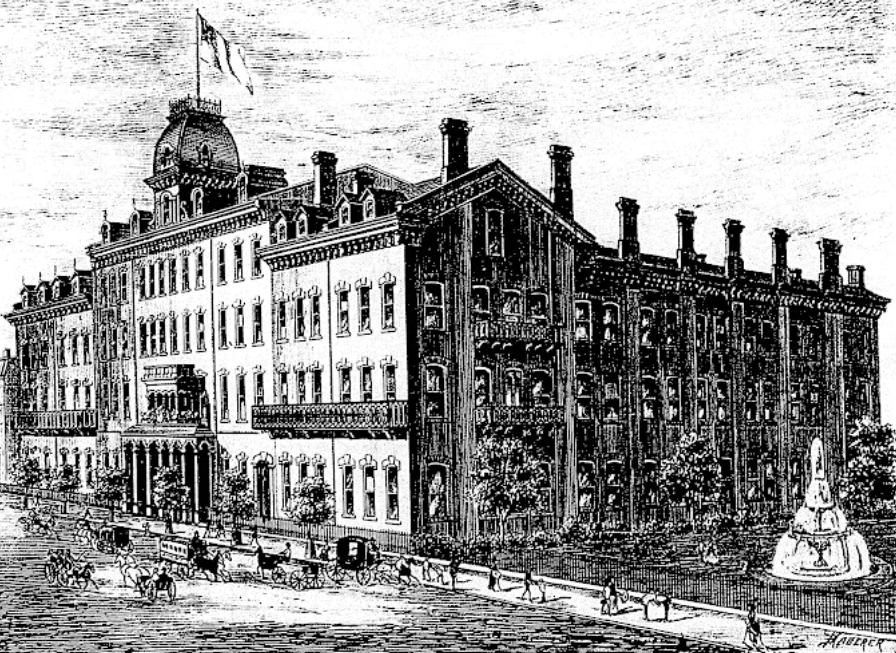

Wilde’s first lecture in Canada was in Montreal on May 15, 1882. In a letter to a friend he drew a sketch of the view from his room in the Windsor Hotel—a gigantic but un-Aesthetic poster of his name on a wall across the street—commenting, “anything is better than virtuous obscurity, even one’s own name in alternate colours of Albert blue and magenta and six feet high” (Holland and Hart-Davis 168). He then went to Ottawa and Quebec City, returned to Montreal for a second lecture, and then made his way to Toronto via Kingston and Belleville. He arrived in Toronto on May 24th, Victoria Day, and was driven to the Queen’s Hotel, which was situated on Front Street where the Royal York Hotel currently stands: “Little ragamuffins chased his carriage…shouting, ‘Oscar, Oscar is running Wilde.’ Wilde loved it” (O’Brien 97).

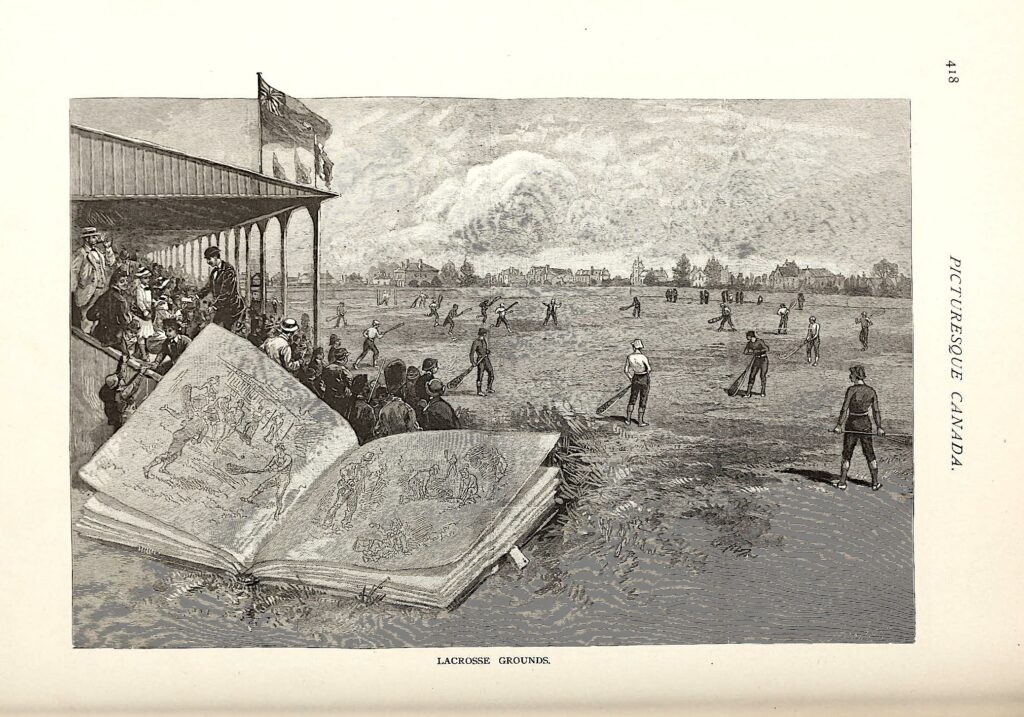

After lunch at the hotel, Wilde was taken to one of the Victoria Day events, a lacrosse match at the Lacrosse Grounds at the northwest corner of Jarvis and Wellesley Streets, situated in what is now Toronto’s Gay Village neighbourhood. The book Picturesque Canada (1882) included an illustration of the Lacrosse Grounds and gave this description:

“At the corner of Wellesley and Jarvis are the grounds of the Toronto Lacrosse Club, a favourite resort of the athletic youth of the town, and, on gala days, of their fair admirers. The field is kept in fine order. Upon it many an exciting contest has taken place between the local and outside clubs, the home team generally succeeding in carrying off the laurels” (422).

Wilde sat in the Lieutenant-Governor’s box, attracting much attention from the spectators, as reported by the Toronto newspaper, The Globe:

“As he passed through the gate, someone shouted ‘Here’s Oscar Wilde.’ The intelligence soon passed along the rows of seated spectators, and all eyes were at once strained to catch a glimpse of him. … Without noticing the sensation his arrival had created he reclined his head gracefully on his hand, assuming the aesthetic attitude, and gazed earnestly into the field where the teams were preparing for the fight” (“Oscar Wilde. Arrival”).

The reporter went into considerable detail about Wilde’s appearance:

“He was dressed in a grey tweed pair of trousers and cobweb-coloured velveteen coat and vest; his necktie was a dark green in colour, tied loosely around his neck, and covering his shirt front. He wore a handkerchief to match. He had a flowing coat, with a deep velvet collar, and secured to his form by a tasselated cord, which passed across his chest. He wore a black felt hat of unusual proportions. The earnest or intense expression of his almost feminine face, his long flowing hair, and his tall, handsome figure, and graceful movements gave him a striking appearance, producing immediately a favourable impression” (“Oscar Wilde. Arrival”).

The lacrosse match was between the “Torontos” (the Toronto Lacrosse Club) and the “St. Regis Indians.” St. Regis was a name given to the Mohawk nation at Akwesasne, which straddles the current provinces of Ontario and Quebec and the state of New York (the American portion is still federally recognized by the name “St. Regis Mohawk Reservation”). The Globe reporter observed:

“When the game was started he evinced the most lively interest, and as it progressed his enthusiasm seemed to keep pace with the players, for he laughed heartily when any of them went unceremoniously to ‘grass,’ or clapped his hands when a good piece of play was done” (“Oscar Wilde. Arrival”).

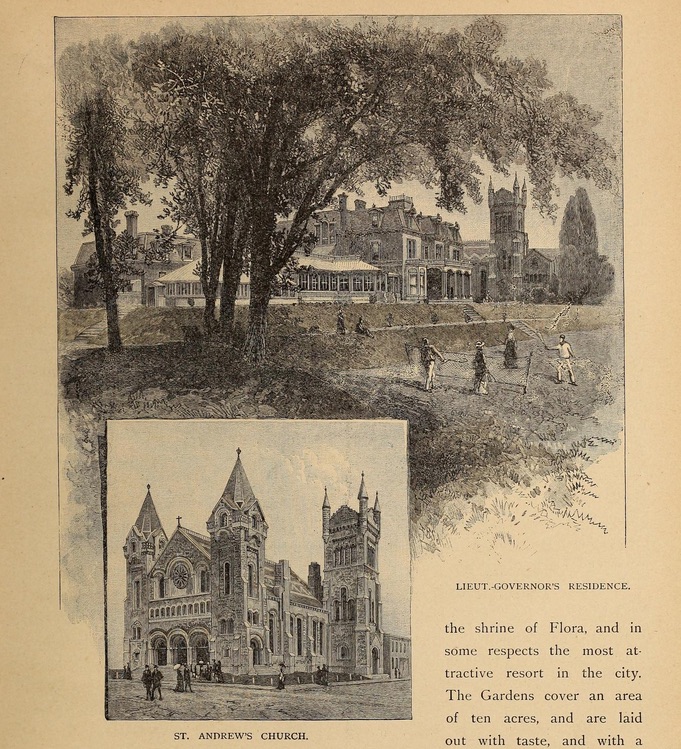

In the evening, Wilde dined at the Toronto Club at Wellington and York Streets, which still exists today (although the current building dates from 1888). He then attended a ball given in his honour at Government House, which stood by St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church at King Street West and Simcoe Streets (O’Brien 100).

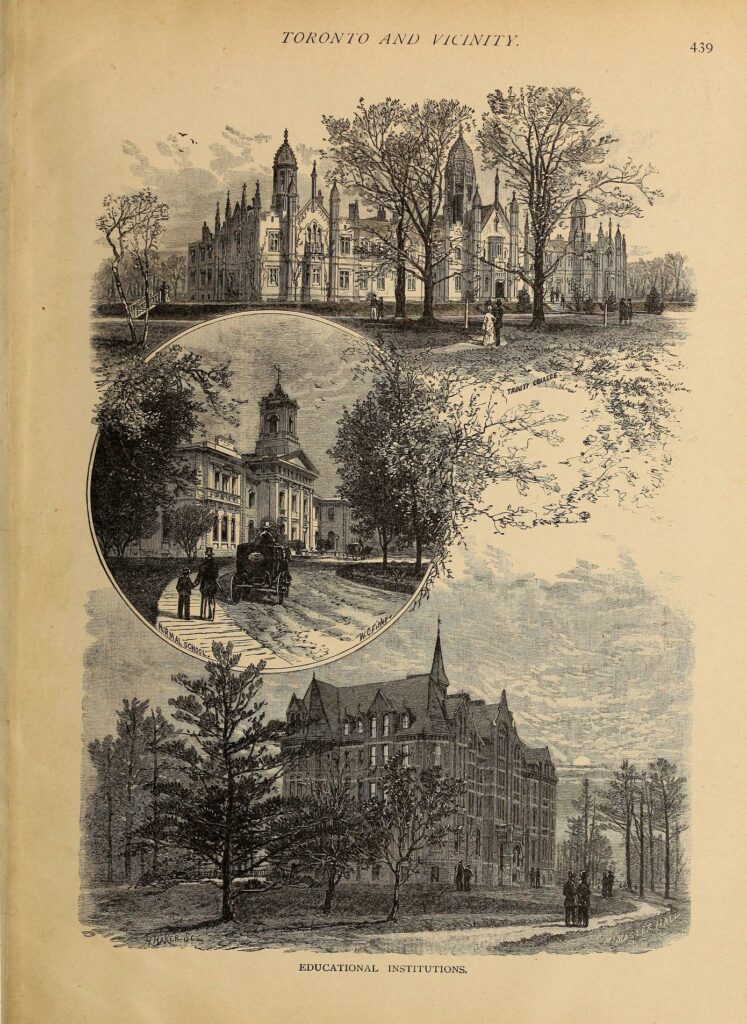

The next day, Wilde attended the Exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists in their rooms on King Street West by Yonge Street. While attendance at the Exhibition had been poor, on the day of Wilde’s visit it was packed: the visitors were apparently more interested in seeing Wilde than the art (O’Brien 102). Wilde then toured the University of Toronto (O’Brien 105).

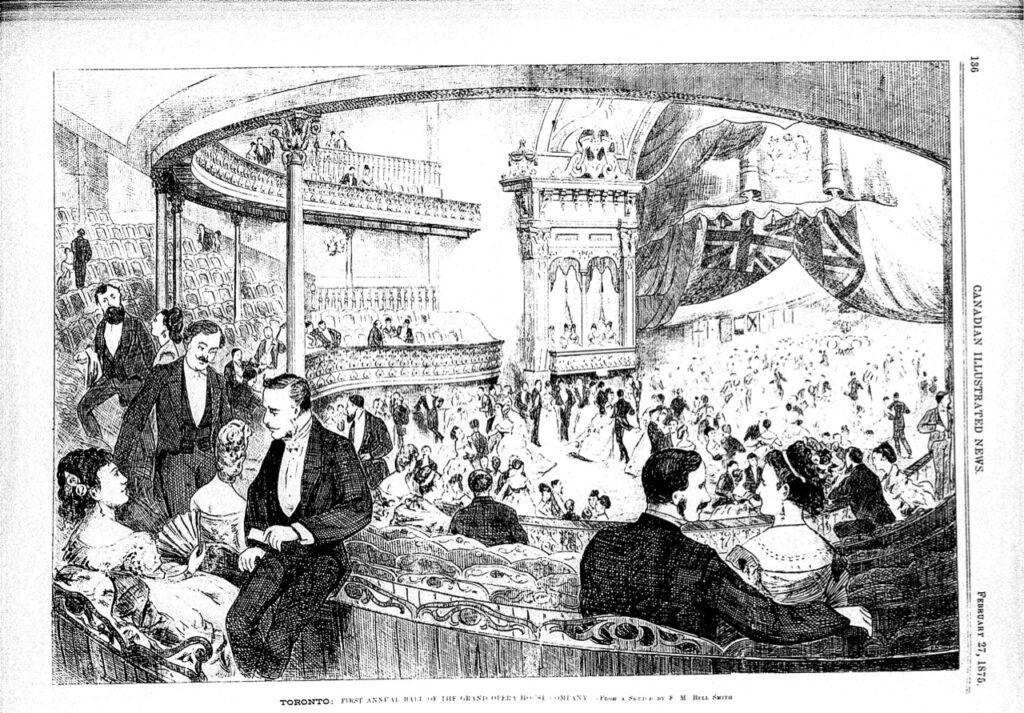

Wilde’s lecture that evening, at the Grand Opera House on Adelaide Street West, was on “Art Decoration.” The Globe reported that “seldom has any lecturer in this city secured a more representative or elite audience” (“Oscar Wilde. Lecture”).

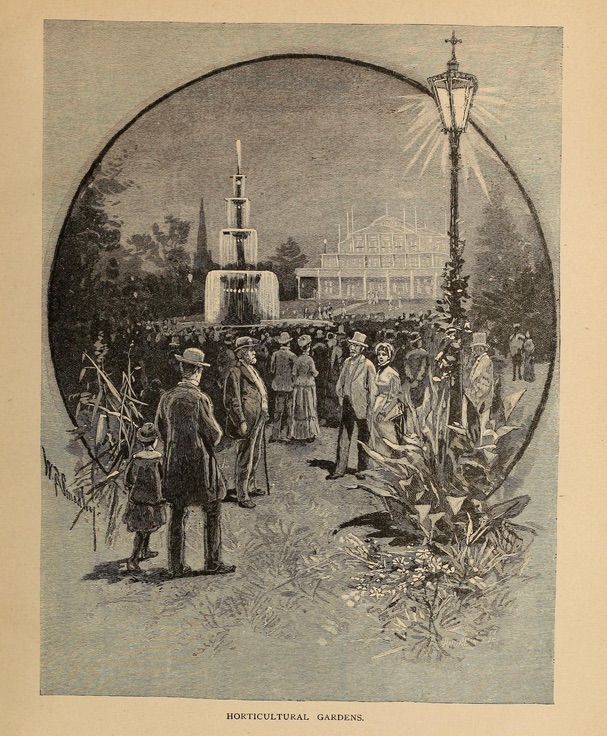

After giving a lecture in Brantford on May 26th, on May 27th, he gave a second lecture in Toronto on “The House Beautiful” in the Pavilion at the Horticultural Gardens (now Allan Gardens). After the lecture he was the guest of Henry Pellatt Jr., who later built Casa Loma. That evening he sat for a bust by the sculptor Frederick Dunbar (O’Brien 109-10). An example of Dunbar’s work can be seen as part of the monument in Sir Casimir Gzowski Park on the Lakeshore: the bust of Gzowski is by Dunbar. In the June 2, 1882 “Local Briefs” column of The Globe, there is a notice that the “plaster cast” of Wilde “has been placed in the art exhibition” (its fate is unknown). Another intriguing notice in the same column states: “Two young ladies living on Seaton street [a couple of blocks west of the Horticultural Gardens] dressed in men’s clothes the other night and went out calling on residents of that street.” Toronto in the 1880s was perhaps a bit queerer than might be assumed!

While most of the Toronto newspapers were respectful and even complimentary towards Wilde and his aesthetic message, one paper, the Evening News, consistently attacked Wilde, pretending to mistake him for a female, “Miss Oscar Wilde.” A fictional scenario in one article has Wilde ‘confessing’ that, despite his appearance and ‘feminine’ interests, he is actually man: “‘Yes, I am a man. It is a painful thing for me to say. It is the skeleton in our own family, the blot on my life, the clog which drags me down and embitters my existence. Oh! If I only had been a woman!’” (qtd. O’Brien 108). Coverage like this may have inspired his epigram in The Picture of Dorian Gray: “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

After leaving Toronto, Wilde lectured in Woodstock and Hamilton, then returned to the United States. In October, he lectured in the Maritime provinces, before sailing home from New York on December 27th, 1882.

Sources

Canadian Illustrated News. 1869-1883. Canadiana, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06230.

Cooper, John. Oscar Wilde in America, https://www.oscarwildeinamerica.org/.

Ellmann, Richard. Oscar Wilde. Alfred A. Knopf, 1988.

Holland, Merlin, and Rupert Hart-Davis, eds. The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. Fourth Estate, 2000.

Howard, Richard. “Wildflowers.” Two-Part Invention. Macmillan, 1974. Reprinted on the Poetry Foundation website.

“Local Briefs.” The Globe (Toronto), 2 June, 1882, p. 6.

O’Brien, Kevin. Oscar Wilde in Canada: An Apostle for the Arts. Personal Library, 1982.

“Oscar Wilde. Arrival of the Apostle of Aestheticism in Toronto.” The Globe (Toronto), 25 May, 1882, p. 3.

“Oscar Wilde. Lecture in the Grand Opera House Last Night.” The Globe (Toronto), 26 May, 1882, p. 6.

“Oscar Wilde’s tomb.” Wikipedia.

Picturesque Canada. Edited by George Monro Grant; Illustrated under the supervision of L. R. O’Brien. Beldon Bros, 1882, Volume I.

Further Reading

Bartley, Jim. Stephen and Mr. Wilde. 1994. A play that takes place during Wilde’s time in Toronto. Set in the Queen’s Hotel, it is an imaginative recreation of the relationship between Wilde and his valet during the lecture tour, a Black man named Stephen Davenport.