The Gothic Interpretations of the Domestic Space

© Copyright 2017 Aishwarya Mehta, Ryerson University

Introduction

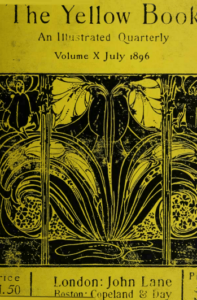

In the short story “The Villa Lucienne” by Ella D’Arcy, a group of women visit the beautiful yet eerie Villa Lucienne in hopes of buying the property. Here they encounter an uncanny housekeeper in the form of an old man and an unknown womanly presence. What entails is a chilling yet indescribable account of what the women experience as they venture through the villa, entering a universe that seemingly revolves around the dark energies of the house keeper, and the unseen female presence (D’Arcy). This story of the gothic horror genre delves into the cultural issue of the relationships within the domestic space. During the 1890s, more and more people were challenging the ideas of marriage and the domestic space, pointing out the flaws in the marital system at the time. The roles of women and men within the system were also analyzed, as shown through the unseen relationship between the housekeeper and the ghost lady in this story. D’Arcy was one of the many Victorians who questioned marriage in the 1890’s as she was a writer who was often criticized for her modern writing style, which challenged the traditional female and her moralities (Knechtel). She aimed to represent a diverse group of women, who were growing with the new period. “The Villa Lucienne” is featured in the 10th volume of The Yellow Book, along with other gothic stories through the perspective of women, or centered around a heroine. It also features an poem called “Ill Omen” by Frances MacDonald, which invokes similar themes of women and the gothic as “The Villa Lucienne”. This volume captures the essence of the unconventional ways people began to see marriage and family in the 1890s and the flawed patriarchal system that overpowered in all domains.

1890s Topic Context

During this era a controversial issue that gained much attention was the idea of the domestic space as being negative and restricting of women’s rights and freedoms. The growing population of the “the New Woman”, a term coined to represent women challenging the conservative and traditional barriers imposed on them and demanding more independence, began questioning women’s roles in society and their unfair depictions as simple domestic beings. They viewed the conventional marriage as “degrading” and an “oppressive institution”, due to their status as “inferior” to their male counterparts (Diniejko). They also resisted the title of “The Angel of the Home”, a concept that dictates that a woman should be “devoted” solely to her husband and submissive to his needs, taking on the role of a housewife, homemaker, and child bearer (The Angel in The House). Many women writers, including D’Arcy, explored the world of the domestic woman through writing and the “standard representations” of her at the time, as can be seen in the “The Villa Lucienne”, through the character of the ghost, and her confinement within the villa. This caused an uproar amongst male publishers who refused to publish her story, as they claimed, “marriage was a sacrament and should not be treated so summarily” (Knechtel). However, the women during the Victorian Era seemed to believe otherwise, as they made tremendous efforts to voice their taboo opinions.

Many of the issues of the “New Woman” were conveyed through the subgenre of women’s gothic, as it expressed the deepest thoughts of women. Gothic fiction is writing style that utilizes fear, gore, horror, and other dark topics in order to invoke suspense and thrill within readers. It was typically used as a writing genre to explore themes that weren’t “acceptable subjects for discussion” within conservative societies (Buzwell). Though the genre didn’t originate in the 1890’s, it constantly adapted to “reflect the times in which it lives” (Buzwell). During the Victorian “fin de siècle”, the genre was adopted by “the New Woman”. The gothic appealed to the underlying anxieties women had regarding the lives they lived in the Victorian era as well as the dark desires, fantasies, and uncertainties they had during the time. D’Arcy articulately uses the gothic to express this fear within woman, as they unknowingly step into an unsafe domestic space, and are ultimately vulnerable to the mysterious nature of the Villa. Through gothic writing women expressed their contemporary fears and desires, which shape the narratives they impose on history, and allow them to freely express their thoughts on society and their role within it (Liggins).

Critical Claim

Through its uncanny yet apprehensive atmosphere, the Villa, in “The Villa Lucienne”, personifies the traditional domestic relationship of the 1890s as a tyrannizing and unnerving space for women to live in. This story indicates that the Yellow Book, specifically the 10th volume, was a platform that supported feminist views of authors like D’Arcy and allowed them to express their utmost doubts and uncertainties within the boundaries of 1890s culture. My analysis depicts that the Yellow Book was an outlet to deliver the idea of the New Woman, and express the restricting cultural issues in the Victorian society through the perspective of women themselves.

Critical Analysis

The Villa Lucienne embodies a woman in a traditional martial relationship during the Victorian Era. The villa is described as “dilapidated”, and “mournful” looking” (D’Arcy 280) and gives off an “eerie, uncanny” feeling to the group of women visiting the villa (283). It personifies the ambiguity women began having during this time, in relation to their status in their marriage. D’Arcy uses these terms to portray the villa in order to engross women in the masculine space of the gothic, giving them an authoritative voice to carry their doubts and fears (Stoneman). D’Arcy also foreshadows the ghastly nature of the house before the women even step into the home, as she depicts several images of death and decay, such as “lichen, deathstool and a spongey moss” (D’Arcy 277) in the dark alley way. This contrasts the traditional view of a home, which is meant to be safe and comfortable with the “Angle of the Home” safeguarding its pureness. Yet the story describes the villa to be full of “incommunicable thrill[s]” (275) and

shows it to instill nothing but fear within the women. D’Arcy also uses specific language and imagery to convey the unnerving fears women have within a marriage, and their lack of freedom within it. She describes the house as “sombre”, “neglected”, and shuttered” (274), projecting the feelings of a woman in an unhappy marriage onto the house.

The women further depict this oppression throughout the story as they undergo significant characteristic changes. Cécile, “the least nervous of women” (D’Arcy 283), decides to go up to the villa on her own, to save her companions the trouble of the journey. However, upon entering the villa, she insists that they all join her. She later accounts that a “terror [so real]” had “laid hold of her when going up the steps to the door” (283). These women are portrayed as independent and joyous, as they venture through the south, however, as soon as they enter the villa they suddenly become vulnerable and consume the fears the villa projects. They also account that “the change from the gay and scented garden to the dark alley, heavy with the smells of moisture and decay, was quite depressing” (277). Women in Victorian Britain, were quite independent, however after entering a marriage, all characteristics of status and socialism were disregarded as a woman, and her child and property, were now under the “control” of her husband (Sykes). As with the domestic relationship, the women became weak and submissive to an empowering and masculine force, in this case the house, and lost their sense of self. Victorian women were seen to immediately conform to the idea of being “naturally” submissive to their male counter parts (Sykes) upon entering the martial union, as do the women in the story upon entering the villa. D’Arcy emphasises this idea of “reinforce[ing] the ‘natural’ hierarchy between the sexes” during the Victorian era as men typically married younger women (Hughes). It was very important to have a distinction between a man and a woman during this time, and proving dominance over his wife was one way to do so. This can be seen through the way the women become subjected by the presence of both the villa and Laurent, as latter naturally become dominant over the women, without any previous interactions or any judgement of ones intellectual or social standing. In the tale the house embodies this dominating presence and consumes the women into its mysterious and anxiety-ridden realm.

Laurent, the “surly” house keeper (D’Arcy 280), is also a notable character, as he is a dominating presence throughout the story, yet seemingly the only male figure. When the women first meet him, he is said to have “suspicious and truculent little eyes” (279). He immediately has a hold over them, and compels them into a sort of submission to his presence, as they all fear him for unexplainable reasons. The women themselves feel the “oppression of his ungenial personality” (281). Even when the narrator feels the ghostly presence, she is unable to speak because “a glance at Laurent froze the words on [her] lips” (283). His “oppression” on the women is so strong that they cannot even speak in front of him out of dread. Sykes explains that in the Victorian culture, there was a parallel between “the bondage of women to men with the abhorred and recently abolished slave trade” (Sykes). Women were subjected to this “primitive social interaction based on power and force” (Sykes). Laurent holds the power within the villa, as he knows its secrets and dark mysteries. He then uses this power to enforce dominance over these vulnerable women. It is also considerable that Laurent expresses this dominance over the ghost woman as well. All that remains of her is a fragment of her lace, which induces an “an overwhelming pity, succeeded by an over whelming fear” within the narrator (D’Arcy 283). She begins to pity the ghost lady, as she seems trapped within the corridors of the villa. She is confined within a figurative marriage with Laurent, who, despite her gothic and frightening features, seems unfazed by her presence. She becomes a sort of slave to his dominance, as explained by Sykes. D’Arcy depicts that women in a marriage, alive or dead, become oppressed when they enter the world of men, and their “natural” instinct to have hierarchy, despite any external factors.

In Conclusion

This story, along with others in the 10th volume of the Yellow Book, narrates the actual experience of a women within a marriage in the Victorian society, through a fictitious gothic tale. D’Arcy’s representation of the traditional marriage is crucial in understanding the experience of women in the 19th century. Writing a women’s gothic story allows readers to experience the world through women’s perspectives, and take part in the anxieties and fears they held within their person. The 10th volume of the Yellow Book contains many women’s fiction stories, and art works, including a poem called “Night and Love” by Ernest Wentworth. In the poem, a woman recites her anxiety of the night ending, for when the night is over her lover will be gone (Wentworth). Though this poem is not of the gothic genre it can be compared to “The Villa Lucienne” as it also conveys the anxieties a woman feels towards, and because of, a man. She is dreading his departure and becomes vulnerable, begging for the night to be longer. In both narratives women are seen to become vulnerable in the presence of a male figure, who intentionally or unintentionally confines them into a domestic mindset. This representation of woman in the Yellow Book shows how during the time the book conveyed conservative themes, critiquing them slightly, and displaying them through a woman’s perspective. Analyzing these texts shows how the Yellow Book gave women and their anxieties, a voice, which at the time was very rare. It allows the “New Woman” to reject some features of the feminine role, attack marriage and sexuality, and free herself from the “can’t”, all done through writing (Cunningham). Yet despite its attacks on the conservative role of a domestic woman, the Yellow Book was received well, and D’Arcy was especially praised for her “powerful and passionate” writing (Zangwill). The Yellow Book became an outlet, not only for women to express their innermost feelings, but for the world to understand and adapt to the thoughts of the “New Woman” through gothic writing.

Works Cited

Buzwell, Greg. “Gothic fiction in the Victorian fin de siècle: mutating dodies and disturbed minds.” The British Library, The British Library, 26 Sept. 2014, www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/gothic-fiction-in-the-victorian-fin-de-siecle.

Cunningham, A. R. “The “New Woman Fiction” Of The 1890’s.” Victorian Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, 1973, pp. 177, Periodicals Archive Online, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1304751003?accountid=13631.

D’Arcy, Ella. “Two Stories.” The Yellow Book 10 (July 1896): 265-285. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. [Date of access]. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV10_darcy_two_stories.html

Diniejko, Andrzej. “The New Woman Fiction.” The Victorian Web, 17 Dec. 2011, www.victorianweb.org/gender/diniejko1.html.

Hughes, Kathryn. “Gender Roles in the 19th Century.” The British Library, The British Library, 13 Feb. 2014, www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/gender-roles-in-the-19th-century.

Illingworth Kay, I. “The Yellow Book, An Illustrated Quarterly Volume 10.” Front cover artwork from The Yellow Book, vol. 10, 1896. The Yellow Nineties Online, Ryerson University, 2005. Public Domain

Knechtel, Ruth. “Ella D’Arcy (1851-1939).” The Yellow Nineties Online . Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. [Date of access]. http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=darcy_bio.html

Liggins, Emma. “Female Gothic Histories: Gender, History and the Gothic. “Literature & History, vol. 22, no. 2, 2013, pp. 121-123, Research Library, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1449474254?accountid=13631.

Stoneman, Patsy. “Gothic Feminism: The Professionalization of Gender from Charlotte Smith to the Brontes / Gothic Forms of Feminine Fictions.” Journal of Gender Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, 2000, pp. 108-110, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS); Research Library; SciTech Premium Collection; Sociology Collection, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/214571377?accountid=13631.

Sykes, C. “Naturalized Oppression: John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women and The Spectator’s.” Victorian Culture and Thought, University of Victoria, 25 Mar. 2014, victoriancultureandthought.wordpress.com/2014/03/25/naturalized-oppression-john-stuart-mills-the-subjection-of-women-and-the-spectators-miss-taylor-versus-the-pall-mall-gazette-on-marriage/.

“The Angel in The House.” Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press, 2017, en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/the_angel_in_the_house.

Views of the villa at Pratolino’ (Vues de la villa de Pratolino)<br/>Stefano della Bella (Italian, Florence 1610-1664 Florence). The villa at center flanked by four obelisks, a staircase to either side, a statue in a niche in center of staircases, various figures and dogs below, from ‘Views of the villa at Pratolino’ (Vues de la villa de Pratolino). ca. 1653. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. http://library.artstor.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11305457. Web. 24 Nov 2017.

Wentworth, Ernest. “Night and Love.” The Yellow Book10 (July 1896): 259-260 The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. [Date of access] http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV10_wentworth_night.html.

Zangwill, I. Rev. of The Yellow Book 10. Pall Mall Magazine November 1896: 452. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=review_v10_pall_mall_magazine_nov_1896.html

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.