Queer Sexuality and New Woman Fiction in Charlotte Mew’s “Passed”

© Copyright 2017 Jamie Glazin, Ryerson University

The Yellow Book, Charlotte Mew, Queer Sexuality, and The New Woman

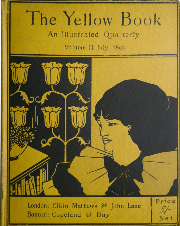

In Charlotte Mew’s short story “Passed”, published in the second Volume of The Yellow Book in 1894, a prime example of a progressive Victorian short story can be seen. The story is about a young woman who went on a walk in London only to run into a distressed, yet compelling woman. The distressed woman brings the narrator to her worn-out home, where her sister lays on her deathbed. The distressed woman in need of comfort, begs the narrator to stay with her for longer than she had wanted to, the narrator refu-

ses and leaves feeling guilty, yet disturbed. Months later, the narrator sees the distressed woman on the street, with a very wealthy man; and though the relationship is not clearly described, there is a sense that the relationship is improper. Throughout the story, there are descriptive words used that illustrated the idea of queer undertones in the story. Due to Mew being homosexual herself, I am curious to know if the unorthodox portrayal of queer sexuality seen within “Passed” is a result of Mew’s sexuality, or because The Yellow Book was known to be an avant-garde and progressive magazine.

Charlotte Mew and 1890’s Sexuality

The fin-de-siècle has been described as a significant time when defining sexuality. The various technologies that were invented to help society grasp a better understanding of the concept of sexuality during this time is the cause of this. It wasn’t until Michel Foucault published History of Sexuality in 1976, did a birth date for homosexuality become publically aware. Foucault said the birth of (male) homosexuality was in 1870 (Furneaux). Many theories argue that lesbianism was not a term used within this time period, while other theorists believe that this term was used fluently within society. Holly Furneaux uses a quote that describes this as “. . .to see lesbian consciousness as at best a late nineteenth-century phenomenon; no lesbian consciousness before the ‘sexologists’ and their theories, because how can you be conscious of what you are if you don’t have a word for it.” Though the Victorian Era, more specifically the fin-de-siècle, is known the be an influential time when studying the development of knowledge on sexuality, there were extreme limits of society adapting to queer desires.

Charlotte Mew’s literary works have been described as commonly portraying feelings forbidden desire and physical pleasure, as well as a fear of madness. This forbidden desire has been defined by uneasy simultaneous feelings of desire for sexual pleasure as well as the assumption that such desires inevitably only cause pain (Walsh 228). Due to lesbianism within this time being seen as a pathological condition, Mew’s theme of fear of madness has been linked to indecision towards passion, a struggle she faced within her personal life. Mew’s fear of madness has been said to have stemmed from her familial history. Mew’s mother, as well as two of her siblings suffered from mental illness. Two of Mew’s siblings suffered from schizophrenia, and at the time were believed to have gone mad; both died in an institution (Walsh 218). Many of the themes seen within Mew’s literary works have been related to her personal life, in terms of of family life, as well as her sexual orientation.

Mew’s work, along with The Yellow Book have both been linked to the New Woman Movement occurring at the time. Kate Henderson says “The Yellow Book (1894–1897) capitalized on dismantling expectations of urbanity through gender and thus actively shaped this project of cosmopolitan deterritorialization: unidentified and unidentifiable women roamed indiscriminately through London in its pages.” (187). Henderson further explains that through The Yellow Books encouragement of authors such as Charlotte Mew and George Egerton, the periodical gained a reputation of being aligned with New Woman fiction (187). Through the messages being communicated through the literature and artwork from The Yellow Book, the societal defiance within this periodical becomes well established.

Critical Claim

Through the narrator’s queer sexual undertones seen within “Passed”, as well as the celebration of New Woman fiction, it is clear that this story is an example of a progressive text. This story is a prime example of how The Yellow Book was a periodical known to support progressive queer and feminist content. Thus, my inquiry will demonstrate that The Yellow Book and Charlotte Mew were both revolutionary in their own names through their disobedience to conform to common day Victorian societal beliefs.

Progressive Victorian Messages in Charlotte Mew’s “Passed”

The second volume of The Yellow Book has been recognized through its alignment to the New Woman Movement through publishing New Woman fiction.The addition of new female authors within the volume spoke for the periodicals progressive attempts to use feminist content within the magazine. The Yellow Book was known to comment on what was occurring in Victorian culture at the time. Authors such as George Egerton and Charlotte Mew produced stories that exploited the interconnection of the Victorian perceptions of the New Woman and urban character; the link between gender and the city (Henderson 187). This holds significance due to the fact that it shows how The Yellow Book used the representation of New Woman fiction, as well as queer sexuality as tools to hold its reputation as being an avant-garde, progressive periodical.

Within Charlotte Mew’s “Passed” there are frequent undertones of queer sexuality. Throughout the scenes in which the narrator is interacting with the distressed, yet compelling young woman, a sense of desire becomes known. An example of this is when the narrator says “I remember noticing, as it swept with her involuntary motions across my face, a faint fragrance which kept recurring like a subtle and seductive sprite, hiding itself with fairy cunning in the tangled maze.” (Mew 128). The sense of sexual desire portrayed within this moment is more of a vague representation, something in contrast to other moments seen within the story. The scent the narrator has picked up on was later related to a “. . .dearly bought bunch of violets. . .” (Mew 129). This undermines the seductive tones between the narrator and young woman, not only because of the smell emerging from the violets instead of the woman, but also due to the fact that within the Victorian Era violets were related to prostitution – a job, not a feeling (Flint 698). Throughout this story, it was not sexual acts that illustrated the sense of queer sexuality, but it was the same-sex desire that emanated from the interactions between the two women.

The narrator’s description of the woman’s violets and nightstand was disrupted, and this was described by saying “A passionate movement of the girl’s breast against mine directed my glance elsewhere” (Mew 129). Though innocent, this action was a distraction in the narrator’s mind. The wording of “a passionate movement”, suggests the queer undertones within this scene. Shortly after this moment the narrator left the woman. What can be understood through the narrator’s rush to leave the woman is that she is not only running away from this distressed woman in her time of need, but she is also running away from herself. The abrupt exit of the narrator is an illustration of how she is running away from acknowledging her own emotional and physical desires (Flint 703). The narrator is suffering from not being able to attain a sense of spiritual or sexual release from the Victorian urban city (Bristow 265). This is significant to the progressive messages within the story due to the fact that the narrator is illustrating the Victorian cultural anxieties that were being experienced. Her queer desire, yet fear of her queer desire represents how society was frightened by their sexual desires – especially their queer desires.

During the Victorian Era queer sexuality between women was seen to be a pathological condition. As a result of this, Mew’s fear of madness can be directly linked to her representation of queer sexuality within “Passed” (Walsh 228). With the narrator’s passion being queer sexual desire, her fear of accepting herself would be due to her fear of being seen as mentally unstable; which is an aspect of Mew’s life that can be seen within her work. The addition of Mew’s fear of madness within her story adds a touch of personalization. The vocalization of Mew’s personal struggle provides “Passed” with an avant-garde and complex verse (Walsh 238). Mew’s personal struggle shining through in her literature provides her message with a more reliable source. Mew’s representation of this fear is now provided with a sense of accuracy, for she knows what this fear feels like.

Within this volume of The Yellow Book, there is an addition of new female authors, the periodical gained a reputation of alignment to the New Woman Movement. George Egerton and Charlotte Mew specifically have been thoroughly researched as two New Woman authors within this volume. Within both Mew’s “Passed” and Egerton’s “A Lost Masterpiece”- another story within Volume 2 of The Yellow Book, there is a clear advocation of the New Woman movement. Within “A Lost Masterpiece” there is an establishment of female presence, and an assertion of the woman’s authority within the story that projects the New Woman onto the reader (Henderson 190). Both Mew and Egerton maintain a focus of commenting on the ways in which women were seen in fin-de-siècle London. Egerton with the concentration on the authority a woman obtains through London’s streets, not influential buildings. While Mew focused on the New Woman as an impulsive urban character that leads the narrator to a female victim of London’s poorer areas, and a misleading sense of the free New Woman in London (Henderson 207). Through the representation of the New Woman both Egerton and Mew produced, The Yellow Book had a complex sense of the New Woman within its pages (Henderson 207). Within just these two stories there are already two different New Woman messages being seen in this volume. Egerton’s focus on female authority in urban cities, and Mew’s focus on female victims and fear of queer desire.

Conclusion

The Yellow Book was able to continue to hold its reputation as a cultural commentator in the second Volume of the periodical. The addition of new female authors reinforced The Yellow Book’s avant-garde character through its direct alignment with New Woman fiction. George Egerton and Charlotte Mew had become two prime examples of New Woman authors within the Volume, and the influence of the fin-de-siècle London was clearly seen within both authors stories. Not only did Mew assist in The Yellow Book’s reputation of being avant-garde through New Woman fiction, but she was also able to extend the progressive messages through the constant queer undertones included within “Passed”. Mew’s willingness to include queer undertones as well as the New Woman Movement within her story represents a side of 1890s culture many Victorians were not comfortable with.

Though there were limits to the Victorian Society’s willingness of acceptance towards homosexual relations and the New Woman, a minimal sense of acceptance had begun in this era. Within the review “Two Original Periodicals” published by the Chicago Times, it was said that “There is a wide variety in the literary contents of the Yellow Book: and there seems to be no disposition on the part of the editors to fall back on the stereo-typed forms of verse and fiction, the bane of periodical literature in England and America. Thought—creative thought—will evidently be prized above cold and soulless forms however polished.”. This review is evidence that again, though the acceptance was limited, the New Woman and homosexual relations were making progress. It was periodicals such as The Yellow Book and authors similar to Charlotte Mew, that were the beginning progressions of these movements.

Works Cited

Flint, Kate. “The “Hour of Pink Twilight”: Lesbian Poetics and Queer Encounters on the

Fin-De-Siècle Street.” Victorian Studies, vol. 51, no. 4, 2009, pp. 687-712.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. Vintage Books, 1988.

Furneaux, Holly. “Victorian Sexualities.” Literature Compass, vol. 8, no. 10, 2011, pp. 767-775.

Ledger, Sally. “Wilde Women and the Yellow Book: The Sexual Politics of Aestheticism and

Decadence.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 50, no. 1, 2007, pp. 5-26.

Henderson, Kate K. “Mobility and Modern Consciousness in George Egerton’s and Charlotte

Mew’s Yellow Book Stories.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 54, no.

2, 2011, pp. 185.

Mew, Charlotte M. “Passed.” The Yellow Book 2 (July 1894): 121-41. The Yellow Nineties

Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010.

Web. [27/11/2017]. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV2_mew_passed.html

Walsh, Jessica. “‘The Strangest Pain to Bear’: Corporeality and Fear of Insanity in Charlotte

Mew’s Poetry.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 40, no. 3, 2002, pp. 217-240.

“Two Original Periodicals.” Rev. of The Yellow Book 2. Chicago Daily Tribune 11 Aug. 1894:

- The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. [27/11/2017]. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=review_v2_chicago_daily_tribune_aug_1894.html

Image Copyright Statement

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.