Stigmatization against Early Pregnancy in “Martha” by Mrs. Murray Hickson

© Copyright 2017 Juvian Gonzales, Ryerson University

◊ Introduction to “Martha”

According to The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle, The Yellow Book is a journal that

provided a cultural forum for genuine dialogue between New Women, Aesthetes, Decadents and other avant-garde writers but began managing a much more cautious editorial policy after the downfall of Oscar Wilde in April of 1895 (Sally Ledger 167).

Further, Ledger states that many female writers contributed to the magazine the minute it was launched, recalling names such as Ella D’Arcy, Vernon Lee, Charlotte Mew, Victoria Cross, etc. (166), but the mentioning of the name Mrs.Murray Hickson goes missing.

Mrs. Murray Hickson is the author of a short-fiction, realism tale titled “Martha“ found in Volume 7 of The Yellow Book. She is not known as a New Women, Aesthetes, Decadents or an avant-garde writer but is viewed as a traditional realist writer (Kennelly 278). Among the female writers who contributed to The Yellow Book, the reason her work is not as exposed compared to the works of her female peers is because of the type of literature genre she works with.

“Martha” is a story that depicts the conventional women of the 1890s based on the characterization of the veteran house-boarders and the narrator who behaves in contrast to Martha, a new servant from Surrey. They are characters who wear certain outfits and are required to complete a list of chores. The narrator thinks naturally that because Martha is from the country-side, she is ignorant who lacks the training to do these tasks expected by the household (Hickson 268). The narrator pities her, saying “Poor little Martha!” (Hickson 272) that results to constant supervision and kind offers, strengthening their bond between one another.

However, the narrator fails to nurture Martha into adulthood at the end of the story. At a young and developing age, Martha becomes pregnant and is thrown out of the boarding-house without the narrator’s knowledge. Through this unfortunate ordeal, the story brings awareness to the stigmatization against early-pregnant women that were a cultural understanding within the female community set in the 1890s Britain time.

◊ “Martha” in support of the stigmatization

The Yellow Book is dominated by male writers and amongst its little number of female writers, most worked actively to support the “New Woman” genre. This genre sought for masculine attributes to be displayed by female characters and the concept of ‘free love’ through the rejection of marriage (Ledger 155-162). This is a transgression to eliminate stereotypical gender roles with a dominant female in possession of her agency that showcases how women should be treated equally, or if not, similarly to men.

“Martha”, on the other hand, is in complete disagreement to this notion.

Mrs.Murray Hickson’s short-story is part of the magazine publication released on October 1895. This was a time where the editorial policy was attentive in terms of choosing which literary pieces should be incorporated into the next magazine volume as pointed by Ledger at the very first paragraph. The short-fiction begins and ends without aggressively attacking the cultural norms. Despite the story not focusing on a heterosexual pair as protagonists, there is little reference to men and no mention of masculinity. “Martha” also shows support for the conventional attitudes and stigmatization towards early-pregnant and unmarried women in the 1890s by displaying the importance on marriage which Martha seemingly mocks for sleeping with a man who she is not sacredly tied to. Instead the story sees the scenario as being problematic and treats unwed woman with child out of wedlock as deviants, which is depicted at the end of the story as the narrator chooses to eventually forget about Martha’s story and her significance.

Altogether, “Martha” goes against what a story based on “New Woman” would be about. There does not seem to be anything particularly transgressing to the story Mrs.Murray Hickson wrote that breaks social and cultural barriers, so it becomes questionable as to why “Martha” was included in The Yellow Book in the first place.

◊ Apparent Cultural Themes in the Victorian Era

“Martha” mimics a realistic situation for women in the Victorian era. According to Jesse F. Battan, there was an “active group of nineteenth-century reformers known as ‘Free Lovers,’ [who] refused to accept society’s categories of deviance” and saw women as “libertine advocates of the irresponsible expression of male sexual desire” (602-23). Due to the overwhelming response to the “New Women” era, women were influenced to rebel against the cultural norms to advocate their human and female values. But society relented. Marriage was sacred in their time and young women were to be educated with proper mannerism that should avoid the scenario leading to early-pregnancy. So activist groups like ‘Free Lovers’ were encouraged to remind women how dangerous too much freedom can be because of the lack of adult supervision that can lead young teens to enunciate false signs of allowing men to sexually explore their bodies.

In addition, and through Cuffe’s published literature piece of “A Reply from the Daughters”, there is the drawing of the idea that young women desired to obtain liberty from their parental figures. Young women wanted to meet men in secret and without the need of their mothers acting as chaperones. By doing so should prove their independence in being able to make their decisions (Ledger 228). In other words, there was a rebellion against the parents. Young female teens felt trapped and limited to their behaviours, believing that parents were reasons for holding them back from reaching their dreams because of the lack of control.

Overall, the community worked together to retain traditional rules about dominant males and submissive females in order to protest against the feminist movement.

◊ the “New Woman”, Contraception and Sexualization in the Victorian Era

The Yellow Book overlapped with the “New Woman” era as female writers fought to write about independent female characters in literature based on how exciting their adventures could be without being tied to a male partner. There was also the engagement to women’s deep and personal thoughts that were not exclusively explored before the launch of the magazine that established this public forum. “Realism” rose in literary genre (Stephen Arata 169) and received a variety of responses. “Martha” is one of the stories that decided to follow this trend of being “life-like” (Arata 171).

In the short-story, “Martha, like Eliza, had been dismissed at once, without a character” (Hickson 278). This pertains to the normal and repetitive occurrences of women being pregnant out of wedlock and being kicked out of their homes due to shame. Due to the literary genre being “realism”, women in the Victorian Era definitely accumulated a high number of young women being pregnant early that made Mrs.Murray Hickson display the scenario in her story as a reflection to present events. It was such a normal occurrence that the narrator could easily move on pass Martha’s story in disappointment, which means that the community in 1890s Britain time would treat these young women as figures not belonging to their group.

Contraception back in the 1890s was seen as improper and unwanted because it linked to the idea of prostitution due to its display of practice that allowed women to have sex without being impregnated (Ana C. Garner & Angela R. Michel 186). Therefore, the reason Martha was kicked out of the residency is because of shame and the subconscious thought of labeling her as a “prostitute” by the public. The minute she became pregnant out of wedlock, she was to be depicted as a horrifying figure in the community who is not worth their time or care, blamed for her own negligent decisions.

Furthermore, when the narrator visits Martha’s mother, she finds “a tall, frail woman, aged pre-maturely by poverty and the stress of early motherhood” (Hickson 279). This part depicts that early-pregnancy seems to run in the family and because Martha had no proper figure to guide her through adulthood, she suffered the same fate as her mother. It also goes to show how the community needs to be stricter in educating young women into learning about the consequences of early-pregnancy and reviewing their methods so the outcome does not continue to happen.

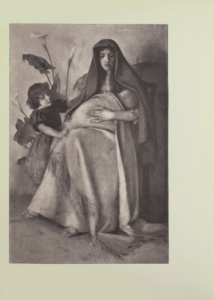

Moreover, during the Victorian era, women were sexualised and “perceived as one of the primary links between men and nature; the force of the tame/wild split thus fell heavily on them… [and] a deeply sexualised polarity between Madonna and whore developed” (Scott 635). Due to the natural course of women being project as sexual objects, women were more lenient to dress and act a certain way in order to demolish this conception. According to Garner & Michel, “[p]olitics and religion merged and would remain the dominant voices over the next 60 years” (186). Since the church had a dominant voice in the community, their perception towards contraception linking to prostitution were believed by the Victorian people to be true.

Therefore, The Yellow Book re-establishes this important notion of following the conventional attitudes in the 1890s as the best decision. By wearing the appropriate clothing, like the dress-code requested for Martha to wear in the short-story, and having her focused on her duties, Martha was to avoid any means of sexualized characterization. This was the hidden intention of the strict actions the veteran boarders portrayed in the tale. The short-story imposes a message to young women like Martha, who is naive towards the environmental effects of early-pregnancy to grow up as intellectuals who follow the cultural norms and expectations set for Victorian women in order to avoid the stigmatization.

◊ In Conclusion: The Yellow Book‘s safe choice

During the 1890s Britain time, early-pregnancy signified prostitution and was a shameful act for a woman to commit. Realism depicted everyday tropes and was heavily criticized with comments based on remarks realist works received such as “inartistic garbage” and “dirt and horror pure and simple” (Arata 17). “Martha” by Mrs.Murray Hickson may seem appropriate to be in The Yellow Book because it can draw these kinds of criticisms as an active response to the magazine, however, there is a more important and hidden value in regards to the inclusion of “Martha” that is beneficial to the magazine as a whole.

“Martha” is not devious or apparent in the rebellion theme unlike other female writers. It stays true to its form of bringing a sympathetic response (Arata 70), a factor to writing a realism fiction. It depicts the present events of early-pregnancy that results to pessimistic ordeals of having the community turn their backs on these young women and leave them helpless.

Therefore, The Yellow Book played safe in order to balance the subjectivity of the magazine into keeping their reputation clean. The magazine included “Martha” in their collection because this short-story does not deliver any problematic scandalous for the public to criticize, other than the small issue of its choice in literary genre. It is instead a piece that supports the cultural understanding of seeing early-pregnancy as an undesirable outcome that then aids in viewing The Yellow Book as an impartial collection of literary works by showing both opposition and support to cultural norms.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.

Works Cited

Arata, Stephen. “Realism.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle. New York: Cambridge University Press, edited by Marshall Gail, 2007, pp.169-183.

Battan, Jesse F. ““You Cannot Fix the Scarlet Letter on My Breast!”: Women Reading, Writing, and Reshaping the Sexual Culture of Victorian America.” Journal of Social History 37.3 (2004): 601-24. https://journals-scholarsportal-info.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/pdf/00224529/v37i0003/601_cftslotscova.xml

Garner, A.C. & Michel, A.R. “The Birth Control Divide”. U.S. Press Coverage of Contraception, 1873-2013, vol.18 (4), November 2016, pp.185-190. Journalism & Communication Monograph, doi:10.1177/1522637916672457.

Hickson, Mrs. Murray [Mabel Greenhow Kitcat]. “Martha.” The Yellow Book, vol. 7, The Bodley Head, October 1895, pp. 267-279. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Dennis Dennisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University, 2011. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV7_hickson_martha.html

Kennelly, Louise. “PRÉCIS.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol.39 (2), January 1996, p. 278. Dept. of English, Arizona State University, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1308660409?accountid=13631

Ledger, Sally. “The New Woman and feminist fictions.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle. New York: Cambridge University Press, edited by Marshall Gail, 2007, pp.153-167.

Scott, Anne L. “Physical Purity Feminism and State Medicine in Late Nineteenth-Century England.” Women’s History Review vol. 8, no.4, 1999. pp.625-42.