Call of the Wild

© Copyright 2017 Thomas Gaspar, Ryerson University

The Busy City

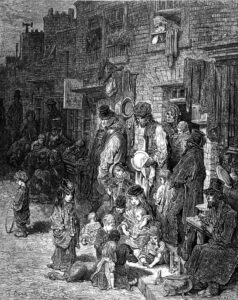

During the Victorian period more than half the population of England were living in cities and towns. It transformed places like London into crowded metropolises more overpopulated than anybody had ever seen or predicted. Despite there being so many people living in such close quarters, there became a frightening lack of social interaction between neighbours. There were relationships formed of course, but they were momentary, created and gone within an instant. (Epstein 511) The concept of people being present and near but really not there at all is exactly how Phillip, from The Return describes his nameless urban lover, “loveless… young woman.” (Henderson 73) At that time, women were being hired more readily than their highly paid husbands, thereby changing the existing family dynamic, (Epstein 510) This would explain why Phillip calls his urban love interest “a little bold.” (Henderson 73) The nameless love interest appears to be a symbol of urban clichés, all of which are portrayed in a negative light.

Negative Perceptions

Compare this to how Phillip Describes Agnes, his rural love interest: “maiden… fresh looking as dawn… frank true eyes, hair like sunshine” (Henderson 73). Agnes is portrayed as the more appealing woman in Phillip’s opinion, but why then does Phillip waver between the two photos? Why does he not choose Agnes instantly? While there was a strong sense of resentment towards industrialism from rural Englishman robbed of their countryside, rural life was harder work than city life. Farm hands had long hours and long weeks that continued though four long seasons only to repeat year after year (Francis O’Gorman 556). Phillip’s leaving the countryside for the city is never given an explicit explanation but there is evidence that Phillip understood that staying with Agnes meant a lifetime of hard labour and so he fled to the city for an easier life, “He considered his cruel silences that had steadily lengthened, and the expression of self-contempt on his face told what he thought of it all now -the weakness and the folly” (Henderson 73) The fact that he returned after only a year, frantic with anxiety brought on by his memories and urban literature, indicate just how difficult this decision was for him. Phillip must decide the course of the rest of his life and he must decide before the train arrives. The moment of his decision is when he tosses the nameless urban lover’s photo out the window and paces, “restlessly from window to window, trampling heedlessly upon his books and papers.” Phillip is symbolically destroying his “urban side,” in favor of the rural. He even says, ‘Thank God’ after finally choosing Agnes’ photo, a conservative thing to say, as if his decision had already made him a more God-fearing English countryman. This dichotomy between the two women is representative of the dichotomy between urban and rural perceptions in the 1890s. Rather interestingly though, this narrative structure in The Return was a common literary structure in Victorian England.

“Returning” as a Literary Device

The literary device of someone returning from a long voyage and being torn between home and away can be traced back to the character of Odysseus in The Odyssey. This has become commonly used to this day (Pipp returning home to the Joe’s impoverished marsh a wealthy young gentlemen in Great Expectations, Aslan returning and then sneaking into the woods to cleanse himself in The Lion the Witch & The Wardrobe, Mitch the rich but lonely and depressed sports writer returning to his terminally ill professor and discovering human compassion in Tuesdays with Morrie.) In the Victorian era however, there was an added aspect. The returned hero would, more often than not, go into nature to heal himself of voyaging toils. (Reed 216) In J.J. Henderson’s The Return, Phillip clearly returns to nature, though not briefly after as a method of healing. Rather, the entire story encompasses this healing process. The two things Phillip is torn between are rural and urban life.

His clear disdain for everything modern is revealed to us in the very first descriptive sentence, “the smart literature he had brought … wearied and even disgusted him … He smoked doggedly at cigarettes for which he had little relish, and glanced over paragraphs of deformed and mirthless humor, … which all aspiring Londoners must master if they would live in the estimation of their fellows.” (Henderson 72) The literature Phillip reads is classified by Henderson here as a core document in urban London life, yet Phillip, despite having lived in London for a year, is still reading the work in confusion as if the meaning still baffles him. Not only is he confused but what parts of the literature he does understand he clearly despises, revealing how little he must have enjoyed his time there.

Phillip’s feelings for his home, and in turn Agnes, are much stronger as shown with such metaphors as, “He felt it as a baptism. The City behind him now began to appear to be something happily far away-a black blot on a pleasant country,” and “The leafy entrance to the wood looked like the archway of some sylvan chapel.” (Henderson 72) His preference for the rural is clearly shown through religious distinctions, being in the countryside is equally as powerful an experience as being with God. Henderson likely uses religious symbolism in the story for its clear metaphoric effect on a more religious 1890s audience, however an even more influential symbolism is employed in describing Agnes. One that is also the larger theme of The Evergreen: “the other a maiden, fresh-looking as the dawn, with frank true eyes, and hair like sunshine.” Words like “dawn” and “sunshine” are used to describe Agnes and through the course of the story she is described as a person who is in tune with nature. In addition, Agnes is described as being beautiful but in a more primitive sense like a child or a wild animal. “Then she tripped upstairs for a packet-a very tiny packet-of crumpled letters, which she hid in her dress. This, to be sure, was very foolish; but many of the letters in that packet were terribly tear-stained” (Henderson 71) What appears to be the innocence of young love in Agnes is actually the claim that nature is morally superior using Agnes’ purity as symbols of moral perfection. Henderson’s modifying of the “hero returning formula” with the “nature-healing” aspect throughout the story is done intentionally to emphasize the larger message of The Evergreen.

This method of comparison using commonly accepted morality of the time is one in tune with the formula of the Hero’s Return which (Reed 219) describes as, “The device of the return was an excellent method for evoking reader sentiment, but equally important, it had sufficient energy, even in its crudest form, to convey a moral.” J.J. Henderson sets up a dichotomy between the natural beauty of Agnes and the English countryside and the emotionally stressed Phillip and Urban London and very clearly pushes the reader towards Agnes. The story’s happy ending with Agnes teaches a clear moral: choose nature over the city, and this moral is in line with Victorian English ideals, “Despite apparent approval of order and social harmony, a growing restlessness to escape existing conditions and an increasing belief that hope rested mainly in those who could so break from the confinement of their oppressive society.” (Reed 249) Henderson uses The Return to appeal to people’s desire for hope, it would have encouraged anyone growing restless to escape their existing conditions. In fact, this revolutionary spirit is shared with other writers and content in The Evergreen.

Patrick Geddes

Little is known of The Return’s author J.J. Henderson, however the spring edition is divided into four categories: Spring in the Nature, Life, World and North. The Return belonging to the “Life” section, naturally has similar themes to a piece called Life and its Science but from an author with extensive biographical research available compared to J.J. Henderson. Patrick Geddes, who even has a biography on the Yellow Nineties website, is referred to as, “The driving force behind The Evergreen.” (Koeenrad 111) He also has a variety of work in the fields of biology, sociology, city planning and The Evergreen periodical itself that are similar to the major themes of The Return. “In the farmer and the gardener, in the sportsman

and the mariner, in all who, outside the life of cities, have elected to do rather than to know or feel.” (Gettes 29) This excerpt is from a paragraph where Geddes writes his thesis that the occupation of biologists, perceived by commoners and its own scientific community as an industrial, laboratory locked field, is actually the opposite. He then continues to call biologists everywhere to follow him into the wilderness “yet here is the stuff of biology.” (Gettes 33) However Geddes’ argument shifts drastically at the end towards city planning. “And thus they begin to discern and prepare for their immediate task—to cleanse and change the face of cities, to re-organize the human hive.” (Gettes 37) This ending, takes the previous arguments about workers in theory and research having to go out into the field and applies it to city planning. Geddes claims that the way to build the ideal, peaceful city is to go out and study what makes people happy in nature, the same way he believes biologist must study live specimens in their habitats. This reasoning is taken and turned into the main theme of The Return by J.J. Henderson. Phillip goes to London to seek his fortune but the city is in an environment that is like the biologist’s laboratory. Only when he breathes the fresh country air on the train and sees the plants and animals welcoming him back on his way to Agnes does he realize, what he really values as fortune is the nature of his rural hometown.

Proem

Besides Geddes’ views on nature the very first piece in the Spring Evergreen titled Proem by W. Macdonald and Arthur Thomson also shares common themes with The Return. Proem is a celebration of spring, and this short story’s plot is well suited to the season. In the city, winter is devoid of life and nature but in spring that life returns like a revolution and those who see it want more. “From urban to rural, from fever to fresh air—that may fittingly be the second rallying-word of Renaissance.” (Macdonald 13) When you examine how nature is viewed as this stimulus of joy it is clear to see how powerful of an effect it would have on Phillip in choosing Agnes. Joy, is much more favorable to how the nameless urban lover who is symbolized as almost a disease, “and they are of service in carrying on the wasting business of that metropolitan life which resembles so much the proliferation of a cancer.” (Macdonald 15) What is accepted today as the modern city, one hundred years ago was a completely in its infancy. A foreign concept that was being accused of causing mass unemployment, the destruction of natural environments, pollution, crime and poverty across the country. All of these cultural issues become heated emotions in people The Evergreen touches on and reveals to people that others feel the same way. The Return is a narrative about small town people (an accountant not a king or an entrepreneur) who in the busyness of cities become lost in the crowd. There is a calming compassion in the text of The Evergreen, best said in the lines of the introductory Proem, “Cities there are and must be, and it is in cities that much of to-day’s work and breadwinning must needs be done. But a more open route from town to country is surely not beyond achieving, nor is it necessary that all the travelling should tend for ever one way.” (Macdonald 16)

Works Cited

O’Gorman, Francis; Flint, Kate, The Cambridge History of Victorian Literature, The rural scene: Victorian literature and the natural world, Cambridge University Press, 2012, Ch 25, pg. 532-550

Epstein, Deborah Nord; Flint, Kate, The Cambridge History of Victorian Literature, Cityscapes, Cambridge University Press, 2012, Ch 24, pg. 510-532

Reed, John R. Victorian Conventions. Chapter Ten: The Return, Ohio University Press, 1975. p. 194-216

Claes, Koenraad. “‘What to naturalists is known as a Symbiosis’: literature, community and nature in the Evergreen.” Scottish Literary Review, vol. 4, no. 1, 2012, pg. 111-129 Academic OneFile, go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&u=rpu_main&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA298614199&asid=ec32000ca6707bdf0546b1ce94466b0f. Accessed 21 Oct. 2017.

Patrick Geddes, Life and its Science. The Evergreen, 1895, pg. 29-39

W. Macdonald, J. Arthur Thomson, Proem. The Evergreen, 1895, pg. 9-17

J.J. Henderson, The Return. The Evergreen, 1895, pg. 69-77

© Copyright 2017 Thomas Gaspar, Ryerson University

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.