The Pastoral Dream in “Lengthening Days” by W.G Burn-Murdoch

© Copyright 2018 Sophia Rinas, Ryerson University

Introduction To The Evergreen

The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal was an Edinburgh based aesthetic magazine published in four installments between 1895 and 1897, each issue dedicated to one of the four seasons (Brooker et al. 123). Conceived and created by Patrick Geddes, The Evergreen proposed a “way of of looking at things” that revealed the “unity” of science, literature and art (Brooker et al. 135). “Lengthening Days,” a story written by W. G . Burn-Murdoch in the 1895 spring edition of The Evergreen highlights this approach.

The tale follows an artist named Mark from London who ventures into the wilderness. He meets his wife on the journey, and together they experience the beauty of nature. The story compares the biology of spring with the transformation of the human spirit. It is only by escaping the industrial backdrop of London that Mark is able to renew his sense of purpose.

As an artist and a writer, Burn-Murdoch was known for a creative style in which “romance always enhanced realism” (Swinney 126). “Lengthening Days” examines the conflict between urban and pastoral ways of living while romanticizing the spiritual benefits of the countryside. The story’s theme illustrates the changes produced by urban modernization and the shifting Victorian mindset toward natural landscapes. It presents the argument that nature based retreats are critical to living a balanced life in an urban setting. As a magazine, The Evergreen depicts the merging of the modern and the traditional as a method by which to achieve both internal and external harmony. In doing this, it enforces the Victorian belief of the importance of leisure as a conduit to self-reflection.

Rural Migration And The Industrial Revolution

In “Lengthening Days,” the depiction of natural landscapes can be seen as a direct result of the impact left by the Industrial Revolution. As Jason Long observes in his book “Rural-Urban Migration and Socioeconomic Mobility in Victorian Britain,” the “economic benefits of migration were substantial” (1). Rural labourers rapidly exchanged country living for city life, marking the first time in “the history of any large nation” that more people “lived in towns than in the country” (Long 2). As the demand for factory labour grew, so did the inequality which accompanied the work. Contrary to popular conceptions of a male-dominated workforce, the Industrial Revolution was primarily founded on the labour of women and children (Foster and Clark 2).

In most cases, all members of a working class family were employed six days a week and worked an average of twelve hour shifts (Foster and Clark 5). Consequently, working class society entered a “severe state of crisis” with the old family structure “collapsing amid the breakdown of the home as the center of production” (Foster and Clark 7). The deepening relationship depicted between Mark and his wife in”Lengthening Days” can be seen as a response to this cultural crisis, with Burn-Murdoch presenting nature based retreats as a strong method for healing family bonds.

For the working class, regulated work hours and wages were eventually introduced through factory legislation (Foster and Clark 8). Preindustrial workers had lived by the rhythms of the agricultural year, but as working hours grew shorter and new holidays came into existence, the leisure patterns of mass society took shape (Mitchell 215). With rail travel both accessible and affordable, camping and trips to the seashore suddenly became fashionable vacations (Mitchell 218). In “Lengthening Days,” Mark travels by sleigh, and Burn-Murdoch makes a point of stating that “trains and steamers” are left behind. There is a clear divide between the “machinery” of London and Mark’s more “natural” method of travel.

In writing the story this way, Burn-Murdoch implies that in order for Mark to fully experience the purity of his pastoral destination, even the transport used to get there must shed all pretense of modern life. In her book “Daily Life in Victorian England,” author Sally Mitchell illustrates the influence of travel when she states that natural history was a particularly popular Victorian pastime, as it gave suburban people “a reason to make trips into the country” and a “way to bring nature home” (237). It is evident that part of the appeal of being an “amateur naturalist” for the Victorians was the prospect of the journey it took to get there.

In comparison to the cramped, dirty confines of city streets, blue skies and open fields offered a welcome respite. Leaving city life for the woods and beaches was undoubtedly emotionally cleansing, much like Mark’s journey from London to the South in the story. Furthermore, the ability of Victorians to enhance their fossil, insect, and dried flower collections by way of the trip allowed for a continued sense of “nature” within the home.

Idealized Views Of Country Living

As author Dennis Denisoff observes in his book “Fluid Margins: Natural Environments in Victorian Culture,” for Victorians living in an “increasingly complicated, urbanized environment,” the concept of pastoral living had “come to embody simplified civilization” (3). Denisoff further explains the nineteenth century vision of a “rustic Golden age” captured within the idea of a rural cottage, a “universal image of the past” used to represent a “lost paradise” (29). Mark’s home with his wife in the wilderness is the embodiment of this. In her essay on “Rural Women and Urban Extravagance,” author Janice Helland expands on the Victorian view of the cottage by depicting its impact on the concept of pastoral living through popular entertainment.

She explains how exhibitions held in 1888 and 1897 displayed “reconstructed mock villages” meant to duplicate living conditions within actual farming communities, their quaint exteriors hiding the hardship and poverty which accompanied true farm life (Helland 179). She goes on to describe how such exhibitions were used to “romanticize the rural Celtic fringes of Britain” for the people in London (Helland 179). The villages, in line with the popular and blossoming arts and crafts movement of the period, sold traditional handicrafts as souvenirs (Helland 189).

In the “The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines,” Peter Brooker explains that the goal of the arts and crafts movement sought to create a “socially conscious” element in art and “uphold high standards of craftmanship” (120). Brooker points out that The Evergreen was a byproduct of this trend, as it was one of the first magazines to become “self-conscious” and view itself as “a work of art” by paying detailed attention to its paper and printing layout (127). The Evergreen also exemplified the concept in another way, by utilizing the Victorian interest in the pastoral through its design elements. Brooker states that a principle of the movement was its “promotion of nature,” a theme echoed in the “tree motif” of The Evergreen’s cover as well as the magazine’s title (130).

It is apparent the outward, Celtic inspired beauty of The Evergreen spring edition further idealizes the nature-based harmony it seeks to embrace. Its appearance is that of a fairy tale novel, setting the stage for the fantasy inspired landscape within. As Brooker notes in his article, the contents of all four The Evergreen editions depict a community in which the “boundary between work and play are erased,” an embodiment of the ultimate paradise (130).

Nature As Spiritual Rejuvenation

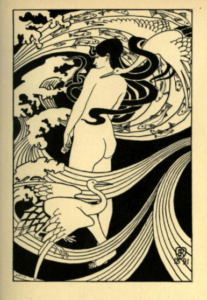

The theme of spiritual rejuvenation portrayed in the paradise inspired landscape of “Lengthening Days” is echoed in a number of other contributions to the magazine. In the picture “Natura Naturans” by Robert Burns, a young woman is drawn surrounded by birds, fish and waves. She is alone, but visibly at peace, her expression implying that she is “one” with the nature that envelops her. In a head-piece by W. Smith, a young girl gazes out into the woods. Like the young woman surrounded by waves, the girl’s appearance is both contemplative and serene.

In the poem “A Procession Of Causes” by W. Macdonald, the author describes the introspection of the soul by using figurative language to depict a person’s immersion in the “blossoming land.” Each piece captures the sense of peaceful isolation and meditation achieved within the confines of nature, reiterating the motifs presented in “Lengthening Days.”

It is apparent that to readers of the time period, the pages of The Evergreen offered a way of accessing the experience and symbolism behind the image of “the rural cottage.” In her essay “Landscape and the Pastoral in the Victorian Era,” author Claire Lawrence states that using “the pastoral tradition” presented Victorian authors with “a formal means of addressing the desire for paradise” (19). Whether through poems of personal reflection or pictures of individuals in harmony with nature, the undertones of a removed, magical environment are the same.

Author Dennis Denisoff elaborates on this idea by writing that the Victorians held the view that the “natural environment was something separate from society” in the sense that it was “beyond civilization’s pale” (7). It represented the “other,” a dreamworld untouched by the blemish of modernism. Denisoff continues that the events of the nineteenth century resulted in “sustained recognition” of the need for humans to “structure their ethics and values” around nature (3). The concept of basing ones spiritual health around the natural environment is shown repeatedly within The Evergreen as the solution to combatting urban society’s ills, and a way in which to achieve internal and external harmony.

In “Lengthening Days,” Burn-Murdoch writes of the manner in which Mark and his wife live off the land. He describes how the two become “beautiful” and “brown with the glare of sunlight,” implying how the environment affects their physical health (45). He goes on to say how the two immerse themselves in the changing seasons and the animals around them, entering into a life which is rich and “great,” and results in a deep sense of freedom. It becomes apparent to the reader that Mark and his wife are no longer “polluted” by the the industrialization of the city. Burn-Murdoch narrates their character growth through the passing months spent in nature in a way that demonstrates they have been internally purified by the very power of their experience.

The Lost Paradise

The change from Mark’s initial, “city based” outlook on life, when he begins the story in a London described by Burn-Murdoch as “gray” and “piercingly cold,” is very different to the image of contentment that Mark exudes at the end (44). Mark begins his journey in a complacent mindset while clearly longing for something more, as evidenced by Burn-Murdoch describing the “spring” Mark feels in his bones. As the story progresses, the reward of Mark’s spiritual invigoration is the book he writes about his experiences.

Burn-Murdoch utilizes this as a way of displaying Mark’s newfound inspiration. When Mark returns to London, the people there read his book with pleasure, indicating that his message regarding the revitalizing aspect of nature has been shared. Burn-Murdoch uses metaphors and lyrical, poetic writing to describe all of these moments, further enhancing the idyllic view of pastoral living that they describe.

Claire Lawrence writes that, for most Victorians, “nature” was a “respository of feeling” and seen as a “sanctuary they were all too eager to retain” (18). It was, above all, “a place where harmony and simplicity reigned” (Lawrence 19). This concept of a “repository of emotion” was central to “the formal aspect of the pastoral tradition” (Lawrence 19). When viewed through this lens, all the poems, stories, and pictures within The Evergreen spring edition can be seen as representative of the various emotions associated with contentment gained through nature. Like “Lengthening Days,” the other submissions are romantic and reflective. Their contents offer a healing alternative to the chaos of the industrialized world.

The Evergreen’s portrayal of the pastoral lifestyle offers insight into the deeply rooted yearnings of a society caught between the old and the new. There is a feeling of wistfulness present within “Lenghthening Days,” and poems such as “A Procession Of Causes,” that can be seen as both idealistic and self-aware. They portray the tranquility of the natural world with beautiful words that also contain a gentle, underlying sadness.

Even as they entice their readers to access the “lost paradise” their tales present, there is a sense that the writers are aware such times have passed. The “solution” of the pastoral retreat is offered in response to the depersonalized, empty existence of urban living. It is effective for the very reason that it offers solitude in the midst of beauty, even if self-reflection in its midst is best seen as bittersweet. As Claire Lawrence writes in her essay, the “green world is a place apart” (20). For that reason, it remains a fairy tale.

- Brooker, Peter, et al. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines. v. II, North America 1894-1960. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Denisoff, Dennis. “Fluid Margins: Natural Environments in Victorian Culture.” Victorian Review, vol. 36, no. 2, 2010, pp. 7-10. Project Muse, http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/article/478547

- Foster, John Bellamy, and Brett Clark. “Women, nature, and capital in the industrial revolution.” Monthly Review, vol. 69, no.8, 2018, pp.1-24. ProQuest, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14452/MR-069-08-2018-01_1.

- Geddes, Patrick, Sir. The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal: Pt. 3. Patrick Geddes and colleagues, 1895.

- Helland, Janice. “Rural Women and Urban Extravagance in Late Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Rural History, vol. 13, no. 2, 2002, pp. 179-197. Scholars Portal Journals, doi: 10.1017/S0956793302000109.

- Lawrence, Claire. “A Possible Site for Contested Manliness: Landscape and the Pastoral in the Victorian Era.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 4, no. 2, 1997, pp. 17-37. Scholars Portal Journals, doi: 10.1093/isle/4.2.17

- Long, Jason. “Rural-Urban Migration and Socioeconomic Mobility in Victorian Britain.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 65, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1-35. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/stable/3875041?pq-origsite=summon&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents - Mitchell, Sally. Daily Life in Victorian England. Greenwood Press, 2009.

- Swinney, Geoffrey N. “From the Arctic and Antarctic to ‘the Back Parts of Mull’: The Life and Career of William Gordon Burn Murdoch (1862-1939).” Scottish Geographical Journal, vol. 119, no. 2, 2003, pp. 121-151. Scholars Portal Journals, doi: 10.1080/00369220318737167.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.