Defending Cosmetics and Decadence in Max Beerbohm’s “The Happy Hypocrite”

© Copyright 2018 Hannah Johnston, Ryerson University

In October 1896, Max Beerbohm’s “The Happy Hypocrite” was published in Volume 11 of The Yellow Book, and as industrialization spread literature across England, writing became a legitimate career and made the medium a household name. These “little magazines” were less expensive than traditional novels, as the platform parted from Victorian morality and instead supported themes of progress and self-determination (Mitchell 262). The educated audience also underwent a transformation; the reader began to turn pages for pleasure more often than for information (Fletcher 196). Thus, an appreciation for art and a regression of Victorian realist ideals paved the way for decadence.

Just as the rest of the late Victorian authors wrote modern and less comforting works, Beerbohm took a conflicted stance to decadence in “The Happy Hypocrite.” The two main characters displayed their aestheticism in contrasting obvious and subtle ways. In the story, Lord George needed to deceive Jenny into believing he was a good man, and once his morals aligned his face absorbed the image of the mask, the piece of art was discarded and the two characters lived a simpler life. On the other hand, Jenny was a spiritual person who would only marry a saintly man, but was easily deceived by a mask, that hid the vain Lord George. These two conflicting sides and how they interact is an example of and definition for decadence, and how the story ends. Decadence in literature can be outlined as an indulgence in art as emotional works filled with symbolism and eternal beauty (Thornton 17). The central characteristics of this luxurious self-indulgence were a retreat from reality that often led to self-parody and self-preservation, a “unique way of seeing … the artificial in life” (Thornton 25).

The decadence in The Yellow Book, whether it was genuine or not, acted out the political reality which lead to “necessary regeneration,” (Fletcher 174) as the press needed controversy and The Yellow Book needed the publicity. Max Beerbohm’s other works, “A Defence of Cosmetics” and “Letter to the Editor” were published in earlier volumes but constantly portrayed decadent themes like aestheticism and costumes, and were full of irony. Though this could have led to confusion, it is important to note that most people who wrote about decadence mocked it (Thornton 22). Thus, “The Happy Hypocrite” is clearly a successful example of decadence, if only to make fun of it, by following Beerbohm’s other artificial and satirical works also published in The Yellow Book. The characters in the story self-indulge in the theatre and appreciate artificial art like masks, but also undergo deeper personal transformations away from the aesthetic, to add a sense of humility to Beerbohm’s favourite subject to satirize.

Beerbohm’s Obviously Artificial Lord George Hell

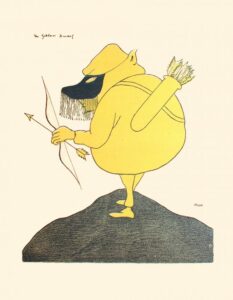

“The Happy Hypocrite” was published at the fin de siècle, but the story was set a few decades earlier in the 1820’s. George IV, the English king who famously lived an extravagant life of leisure, (Fletcher 193) influenced the main character, Lord George Hell, someone who “revelled with the Regent,” gambled and over-indulged in food and drink (Beerbohm 11). The materialistic and dishonest lifestyle was improved slightly by Lord George’s interest in the arts and love of costumes, an idea that could imply some humility to the decadence movement. George had some goodness and praised the acting of one character, the dwarf, especially. Later on, the dwarf returned this gratitude by shooting Jenny with a bow and causing her to fall in love with Lord George (Beerbohm 30). With the deliberate inclusion of French phrases, where decadence was at its height, (Thornton 26) Beerbohm made strong connections between the extravagant society in France and the English audience of this text, and further established a decadent theme. Beerbohm’s exotic sentences such as, “la jalousie se léve de bonne heure” (23) and “il n’y a pas d’épreuve” (37) applied even after the characters began to live more humble lives, and add a flair of emotion and richness to the plot that supported the decadent movement.

The story also incorporated Greek mythology, in the shape of a mask. Mr. Aeneas, the mask maker, wowed Lord George with a tale about the Greek god Apollo, who also had to wear a mask because he wanted to experience nightlife, but when he stepped out the sun rose and everyone went to work (Beerbohm 24). Lord George used a disguise for a more selfish reason, he needed to trick Jenny into believing he had the face of a god, but Beerbohm justified the indulgence of art none the less. Beerbohm stated that “even the unrighteous are a power for good” (13), and applied the decadent love of art to Lord George and his love for Jenny, through the mask he wore for her. The story was not completely pro-aesthetic, and just as society struggled between appreciation for art and fear of vanity, Lord George married Jenny but was filled with pity for her and hatred for himself (Beerbohm 29). The opposing ideas may have seemed indecisive, for not wanting to commit to a wholly decadent piece of literature, or it allowed the reader to sympathize with someone who was obsessed with art and the artificial, who also tried to be honest.

Jenny’s Appreciation for Subtle Decadence

Jenny was an interesting character in “The Happy Hypocrite” because she did not portray a typical, submissive wife, but also because she depicted decadence in an understated but more reassuring way to the reader. Jenny was a young theatre worker, “pretty and talented” (Beerbohm 16) who should have been overjoyed with attention from the narcissistic yet noble lord. Instead, she maintained that she would only marry a man with a saintly face, despite her social standing. One may not consider a beautiful portrait a work of art, but because she waited for a husband who was handsome but also heavenly, Jenny was placing importance on a superficial body part. She, a common girl who danced in the theatre to pay her way, also preserved a spiritual significance about her suitors. Therefore, after Lord George reappeared wearing a saintly mask and the dwarf shot her with another magic arrow, Jenny could rightfully indulge in the art that had become her life.

She was so filled with goodness and love that Lord George underwent another transformation, this one more personal. He donated all his property and swore off earthly goods for Jenny (Beerbohm 34) so her infatuation in his true “art” was justified. After a confrontation with a past lover, George was damasked to reveal the face he was hiding behind all along, Lord George Heaven, that had transformed into the mask (Doniger 116). This new and improved person lived a simple life, never had more than two glasses of wine, and recalled that he preferred his new life to the years spent at Carleton House (Beerbohm 38). The sun melted the mask after Apollo realized the couple no longer needed materialistic forms of art. Through genuine love, the couple could instead look to each other to participate in decadence, and perhaps found aestheticism in the garden of their cottage.

This contradiction, of whether the characters ever really outgrow or overcome decadence, left room for the reader to make their own interpretation, though there was evidence that the couple swore of earthly and fake aspects of their previous lives, for more humble relationships. If love was not a good enough excuse for the reader to accept the normalization of decadence, then parody and satire of the society this story wrote to could also be acknowledged. In a way, Beerbohm cultivated decadence through the couple, but never fully supported it as they no longer appreciated aesthetic art in the end.

Decadence Across Beerbohm’s Other Yellow Book Contributions

Beerbohm’s parody and satire were present in his other pieces, also published in The Yellow Book. If it is hard to ignore trivial characters like Lord George Hell and ironic plot holes about Jenny’s wits in “The Happy Hypocrite,” Beerbohm’s earlier publications “A Defense of Cosmetics,” and “The Letter to the Editor” were examples of pure sarcasm that could have either defended or belittled the decadence movement. As an Oxford undergraduate student, Beerbohm published “A Defense of Cosmetics” in the first edition of The Yellow Book. This work reflected decadence in the “urbane, civilized, witty” 1890’s society in a way that enabled cosmetics, and decadence in general, to laugh at itself (Nassaar 161). In “A Defense of Cosmetics” Beerbohm supported that: “For the era of rouge is upon us, and as only in an elaborate era can man by the tangled accrescency of his own pleasures and emotions reach that refinement which is his highest excellence, and by making himself, so to say, independent of Nature, come nearest to God, so only in an elaborate era is woman perfect.” (68). This essay pointed out societies obsession with perfection and bettering one’s self, and how it could be attained on the outer surface through costumes like makeup. Decadence was stereotyped as feminine (Thornton 16), but Beerbohm argued that cosmetics could also be masculine. Aside from make-up, Beerbohm noted how men could change their face with different styles of facial hair (79). This may sound liberal and empowering, but towards the end an ironic tone was presented. Beerbohm stated that make-up would never be a remedy for age or plainness, but because we could not physically always be becoming, it is best to have these “artificial expressions” so men could change their women if they tired of her (Beerbohm 78).

Critics said that Beerbohm portrayed society in a superficial light, and he responded with his “Letter to the Editor” in the second volume of The Yellow Book and informed his readers that the “defense” was all one big joke. He attempted to explain the “ironic championing of Decadent cult of artifice in order to satirize it” but only furthered the irony of his opinion on decadence, and its reader (Beckson 47). “Letter to the Editor” was intended to display elements of paradox, love of unusual things, and mystery of style (Beerbohm 284) in an obviously ironic way, but this achieved the opposite. He also said that the critics were looking for problems instead of enjoying the beauty, all the while he never directly denied or confirmed his beliefs on decadence. Perhaps “defense” was too strong of a word to describe his emotion towards cosmetics, but by satirizing some of the idealistic views of the decadent population, Beerbohm justified their beliefs to a degree. He named an achievement of true beauty as an accomplishment, whether or not he intended to.

Imitation: The Most Sincere Form of Flattery

Did Beerbohm mature as he started to respect decadence, or was “The Happy Hypocrite” an extension of earlier parody? His decadent works in The Yellow Book were so famously ironic that scholars adopted the term “parotic voice” and applied it to his writings. Jonathan Goldman wrote that Beerbohm liked to represent the unpresentable, that he managed to create arguments for cosmetics, a deceased and unlikeable king, and even himself (301). Beerbohm also liked to use others “literary flavor” as parody (Goldman 300) and may have been supporting decadence only to mock his peers with his lack of seriousness. This begs the question, as with all satirical artists, of when Max Beerbohm was ever himself.

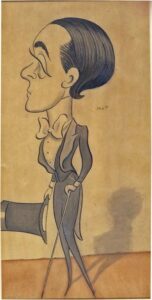

One could draw conclusions from his self-portrait that supported the idea that he took nothing serious. Beerbohm portrayed himself as a balding big head with a disproportioned and unrealistic body shape, and made it more difficult to analyze any of his work in a scholarly way. After all, in “The Happy Hypocrite” he repeated that he was speaking to his “little readers” when The Yellow Book was intended for an adult population.

In a society that was cautious of fairy tales, Beerbohm supported yet another contradictory theme: magical realism, the idea that the supernatural was not problematic (Harris 21). He made a connection between a Greek god and his complete opposite on earth, through a theatre mask and the decadence movement, again, perhaps without meaning to. Beerbohm combined fantasy and more “normal” ideals like courtship, as “The Happy Hypocrite” used the mainstream and the fantastic to challenge common beliefs. Beerbohm did not spare himself, decadence or fantasy elements from ridicule. However, in regards to aestheticism, it is important to note that this was not uncommon at the time, as most people who wrote on or about decadence satirized it (Thornton 22) and mockery is responsible for making it known. Without ridicule from Beerbohm, decadence would not have survived. Some modern scholars have even begun to question whether the movement existed, (Thornton 29) so Beerbohm not only verified 1890’s aestheticism, but also left behind various forms of it, genuine or not, to be interpreted.

Confusion today surrounding “The Happy Hypocrite” and its complicated stance on decadence accurately portray Beerbohm’s reputation in his literary period. The 1890’s are hard to define precisely, a genuine mix of naturalism, realism and aestheticism (Marcovitch 79). The story’s depiction of decadence helped the reader understand The Yellow Book as a whole, or at least sympathize with critics that were just as confused as readers today. While “The Happy Hypocrite” may not have clearly depicted decadence in a singular, complete way, Max Beerbohm wrote to an audience that was equally conflicted on the importance of art and the artificial.

The Yellow Book, and to a degree, decadence, served as the bridge between the Victorian and Modernists, and scholars continue to argue which idea the magazine leaned more towards. Though it may have been mostly mockery and hard to determine as satirical or not, Beerbohm published multiple works on decadence and aestheticism, and acknowledged the movement as factual. He also explored new ways to address experiences, and popularized literature that could explore its own failure (Thornton 29). Modern, societal movements continue to be deeply flawed, so this was a valuable lesson. Decadence was criticized for attacking the simple, manly and wholesome ideas of common English life, as it presented values that were traditionally female and artificial (Thornton 16). Despite a flawed theory, one of the main reasons decadence and aestheticism for art was criticized was because it went against the status quo. Beerbohm may have not intended to humanize decadence in his work, but he at least started conversations around the artificial aspects of society, and less normalized themes, without taking too serious of a tone. This was not meant to imply that Beerbohm paved the way for more indulgent lifestyles, but he did firmly install the belief that decadence was worthy of study as a serious literary period. The readers in the 1890’s and today have the choice to identify with his obvious or subtle examples of decadence portrayed, or, like Beerbohm, simply satirize the movement.

____________________________________________________________________

Works Cited

Beckson, Karl. Aesthetes and Decadents of the 1890’s. Academy Chicago Publishers, 1981.

Beerbohm, Max. “A Defence of Cosmetics.” The Yellow Book, Apr. 1894, pp. 65–82. The Yellow

Nineties Online, www.1890s.ca/PDFs/yellowbookapril189401.pdf.

Beerbohm, Max. “A Letter to the Editor.” The Yellow Book, July 1894, pp. 281–284. The Yellow

Nineties Online, www.1890s.ca/PDFs/yellowjuly189402uoft-COMPLETE.pdf.

Beerbohm, Max. “The Happy Hypocrite.” The Yellow Book, Oct. 1896, pp. 11–44. The Yellow

Nineties Online, www.1890s.ca/PDFs/yellowbookoct189611.pdf.

Doniger, Wendy. “Self-Impersonation in World Literature.” The Kenyon Review, vol. 26, no. 2,

2004, pp. 101–125. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4338587.

Fletcher, Ian. “Decadence and the Little Magazines.” Decadence and the 1890’s, 1979.

Goldman, Jonathan. “The Parrotic Voice of the Frivolous: Fiction by Ronald Firbank, I.

Compton-Burnett, and Max Beerbohm.” Narrative, vol. 7, no. 3, 1999, pp. 289–306. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20107190.

Harris, Jason Marc. Nineteenth-Century British Supernatural Fiction: Folklore and the

Fantastic. Ashgate Publishing Group, 2008.

Marcovitch, Heather. “The Yellow Book: Reshaping the Fin De Siècle.” Literature

Compass, vol. 13, no. 2, 2016, pp. 79-87. Wiley Online Library, doi: 10.1111/lic3.12292

Mitchell, Sally. Daily life in Victorian England. Greenwood Press, 2009.

Nassaar, Christopher S. The English literary decadence: an anthology. University Press of

America, 1999.

Thornton, R. K. R. “’Decadence’ in Later Nineteenth Century England.” Decadence and the 1890’s, 1979.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.