Environmentalism & the Symbolism of Autumn in The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, Vol. II

© Emma Fraschetti, Ryerson University 2018.

In October 1895, J. Arthur Thomson’s “The Biology of Autumn,” and Charles Van Lerberghe’s “The Night-Comers” were published in volume II of the little-magazine, The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal. Patrick Geddes and Colleagues in the Lawnmarket of Edinburgh, as well as T. Fisher Unwin in London published the autumn volume as a part of the magazine’s semi-annual series in accordance with the Celtic calendar of equinoxes and solstices (Janzen). With a background in environmentalism and natural science, Patrick Geddes envisioned a revitalized Victorian future through the unification of art and the natural world. As each volume was published in a different season, The Evergreen’s compilation of folklore, fantasy, and visual art consistently focused on exposing the realities of nature’s progression while bringing forth Celtic culture and aestheticism. Although the scientific essay, “The Biology of Autumn” is stylistically different to the symbolic play, “The Night-Comers,” both emphasize the significance of rebirth and the continuance of life after a time of death and decay. By using the symbol of autumn to represent death as an essential part of the natural world, volume II of The Evergreen served to promote an appreciation for the natural environment and moreover, inspire cultural and social regeneration in its most relevant geographical setting: Edinburgh, Scotland.

Edinburgh in the 1890s

When situating The Evergreen in 19th century Edinburgh, it is important to consider the physical state of the city that influenced the reasoning behind the type of content published in the magazine. A focus towards science, technology, and mechanical skill became increasingly important in Victorian societies (Thomas 52). This shift in ideology concerning efficient living challenged the well-being and happiness of citizens. Evident by Edinburgh’s growing slums, the rapid industrialization of urban regions led to overcrowding and uncomfortable living conditions. Furthermore, the quality of life and mental health of those who lived in city tenement housing continued to worsen (Stalley 163). These inadequately controlled environments in combination with the disregarded maintenance of Victorian cities further necessitated an immediate solution.

Nature as a Remedy

A return to nature was recognized as a methodology for repairing the physical environment which 19th century industrialization had damaged. The injustices created as a result of overcrowding in Edinburgh were to be mitigated by nature. By integrating the natural world with the modern industrial city, society could begin to rehabilitate from the previously fragmented ways of living (Knoepflmacher and Tennyson 67). Not only did the increasingly popular appreciation for nature influence the transformation of Victorian cities to suburbs (Knoepflmacher and Tennyson 55), it also became increasingly relevant in art and means of expression. Evidently, the relationship between culture, society, and nature became prominent as conditions worsened in the city.

The influence of the natural world on art and society can also be seen in literature during this period. In response to industrialization, eco-conscious literature was popularized in order to inspire social and environmental reform. The notion that problems complicating proper living must be represented before they can be solved, was taken on by writers such as Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Thomas Hardy and Henry David Thoreau (Kennedy 18-20). The destruction and pollution of the natural world was emphasized by artists. Moreover, this acknowledgment of the problems created by growing capitalism and consumption was received as an attempt to move suffering Victorian society towards regeneration with nature.

Patrick Geddes and the Natural World

For Patrick Geddes, publisher of The Evergreen, the relationship between society, culture and the natural world was the key to engaging audiences in civic affairs. His studies of botany, biology and zoology inspired a unique outlook on 19thcentury modernization that incorporated an analogy of the natural world. Geddes worked with other like-minded students such as J. Arthur Thomson to apply their knowledge of natural science to disciplines such as economics, sociology, and psychology in order to publicize their ideas and help fulfill the needs of the cities in which they lived (Stalley 17). Although Geddes moved away from his initial background of scientific study, through his relation of nature the humanities, he was able to determine a framework for an improved way of life in Edinburgh.

Geddes sought the betterment of society through education. He believed that the exposure and awareness to troubling aspects of the environment would be the most effective to inspire progress, since merely engaging in perspectives of social problems would not be enough to motivate change (Stalley 27). In addition, Geddes’ focus regarded the acceptance of present conditions in order to work towards a better future. He was considered to be a curator of the future due to his understanding of the urban city within the confines of the natural world (Odum 275-276). Some of Geddes’ contributions to Edinburgh that exemplify this notion are the Outlook Tower built in 1892, the refurbishment of the Ramsay Gardens in 1893 and finally the publishing of The Evergreen in 1895 (Odum 280).

The Northern Seasonal

The effort to portray reality by uniting art and nature was common amongst contributors to volume II of The Evergreen. J. Arthur Thomson, author of “The Biology of Autumn”, was a Scottish naturalist and writer. Thomson’s literary works regard nature and biology from a unique artistic perspective. Moreover, his ability to value the natural world and portray its cruel realities as essential to new life worked to challenge Edinburgh’s negative perception of death. Charles Van Lerberghe, author of “The Night-Comers,” also aimed to encourage an acceptance of nature through symbolism. Lerberghe’s play translated by William Sharp is symbolic in its reference to the realities of the natural world. His particular focus on the artistic representation of autumn serves to highlight the social and cultural significance of the autumn volume of The Evergreen to Edinburgh and its dire condition in the 1890s.

Symbolizing Autumn in The Evergreen

“The Biology of Autumn”

“The Biology of Autumn” is a literary essay reminiscent of folklore, regarding death’s critical role in maintaining the “rhythmic” nature of the four seasons. Thomson explores the migration and hibernation of animals (Thomson 13), dying plant life, and the ripening of crops for harvest which produces seeds that grow into life in the spring (Thomson 12). He emphasizes that although autumn is a period of sleep and death, it is absolutely essential to the creation of new life in the following seasons. As Thomson advocates for the acceptance of death as an essential part of the natural world, he acknowledges that it is generally regarded unfavourably. Thomson personifies “little child Love holding the door against stalwart Death” (Thomson 11) in order to represent the natural human reluctance to accept death as a part of nature. In contrast, he argues for a positive perception of death. Thomson exemplifies the decadence of the fallen leaves, stating that they have a literal “beauty for ashes” (Thomson 12). Through the analogy and symbol of autumn, Thomson discourages identifying death as a definite finality because in doing so, its necessity to the continuance of future life is undermined.

“The Night-Comers”

“The Night-Comers” by Charles Van Lerberghe, translated by William Sharp is a three-act play which draws on Celtic tradition, concerning the cruelty and harsh reality of death. The play takes place in a cottage of two poor women: a sickly mother and a young girl who are repeatedly bombarded with loud knocking on their door in the late night. Although the guests are unexpected and unidentified, the mother greets them as if she were awaiting their arrival. Despite the girl’s confusion and reluctance to let in the guests into her home, they enter to take the life of her mother who happily welcomes death as an end to her suffering. The mother and daughter’s perceptions of death are made evident by the opposing ways they react to the “night-comers.” As the daughter repeatedly denies death, the mother is relieved by it. She refers to dying as “Paradise” (Lerberghe 66) and to death as the “beautiful Lady” (Lerberghe 65) whom she is ready to greet. In personifying the “night-comers,” Lerberghe exposes the nature of death to be unjust yet necessary. Moreover, he conveys that it should not be viewed as devastating but rather accepted as an appropriate end to suffering.

Poetry in Volume II

In addition to fairy tales and folklore, volume II of The Evergreen’s poetic works also represent the themes of autumn. In “Love Shall Stay,” Margaret Armour laments the decline of nature. As she describes the dying flowers and the darkening skies, Armour explains that in spite of the unfavourable realities of nature, she will “make a summer” within her heart (Armour 21). Through Armour’s optimistic perspective of autumn, she is able to exemplify the possibility of love in a time of death and decay. Moreover, this poem serves to inspire a sense of hope. Similarly, Hugo Laubach regards the importance of hope in his poem “November Sunshine.” Whereas Armour explains that she will create and treasure her own hope, Laubach explains that it is “sweet to remember” when autumn grows cold and dreary (Laubach 59). As both of these poems acknowledge the decline of nature, they emphasize that it is only temporary and that perseverance is required to welcome a better future.

Visual Art in Volume II

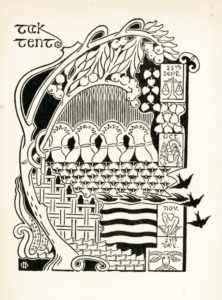

The visual artworks in The Evergreen volume II further contribute to the ongoing representation of autumn and the symbolism of death as an essential part of nature. The ornaments and full-page art pieces of the magazine intended to revive Celtic culture while promoting a view of human life centred around the natural world. Headpieces and tailpieces which decorate the pages of The Evergreen were designed by Nellie Baxter, Marion A. Mason, and Annie Mackie. These small works of linear art resemble waves and swirl-like shapes, signifying the natural progression of the seasons (Janzen). In addition, one of the most striking full-page works of volume II, “Almanac” by Helen Hay, embodies a number of symbols representing autumn. The image depicts the movement of life in an upward motion. At the bottom there is bone progressing to land, then harvest, and finally fruit at the top. In addition, the three blackbirds common to all editions of The Evergreen are flying in a southern direction towards the bottom of the image (Hay 5). “Tak Tent” translating to “Take Care” in Scottish (Janzen) is printed as well on the artwork. All of these symbols in combination moreover emphasize the close relationship between society and nature by portraying autumn as integrated with human life.

Framework for the Future

By examining the symbolism of autumn in volume II of The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, it is clear that the portrayal of death as an essential part of the natural world was intended to inspire social and cultural regeneration in 19thcentury Edinburgh. In “The Biology of Autumn,” J. Arthur Thomson argues not only for the perception of autumn as a season of making way for new life rather than one of “decline and fall,” he emphasizes the importance of recognizing death as necessary to the “continuance” of other life (Thomas 11). In “The Night-Comers” by Charles Van Lerberghe, the girl adamantly refuses to let the “Night-Comers” into her home, furthermore exposing her reluctance to accept death despite her mother’s welcoming of it. As Patrick Geddes sought a better future for the city of Edinburgh by idealizing city environments in relation to nature, it is clear that his intent for The Evergreen was not only to inspire Scottish Renaissance and Celtic revival. The symbolism of autumn in the magazine was the product of Geddes’ motive to progress Edinburgh through a troubled period towards an improved future by integrating city living with the natural world. In and of itself, the cohesive understanding of nature and society’s relationship promoted by The Evergreen was able to serve as a framework and methodology for cultural and environmental betterment in the 19th century.

Works Cited

Armour, Margaret. “Love Shall Stay.” The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 2, Autumn 1895, p. 21. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson UniversityCentre for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/egv2_armour_love/

Geddes, Patrick. Patrick Geddes: Spokesman for Man and the Environment. Edited and introduction by Marshall Stalley, Rutgers University Press, 1972.

Hay, Helen. “Almanac.” The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 2, Autumn 1895, p. 5. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Center for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/egv2_almanac/

Kennedy, Margaret S. Protecting the “House Beautiful”: Eco-Consciousness in the Victorian Novel. State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2013. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing,3614374.

Knoepflmacher, Ulrich Camillus., and G. B. Tennyson. Nature and the Victorian Imagination. University of California Press, 1977.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal (1895-97): Overview.” Evergreen Digital Edition, Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/the_evergreen_general_introduction/

Laubach, Hugo. “November Sunshine.” The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 2, Autumn 1895, p. 59. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/egv2_laubach_november/

Odum, Howard W. “Patrick Geddes’ Heritage to ‘The Making of the Future’.” Social Forces, vol. 22, no. 3, March 1944, pp. 275-281. JSTOR, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2571970

Thomas, Keith. Man and the Natural World: A History of the Modern Sensibility. Pantheon Books, 1983.

Thomson, J. Arthur. “The Biology of Autumn.” The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 2, Autumn 1895, pp. 9-17. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University centre for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/egv2_thomson_biology/

Van Lerberghe, Charles. “The Night-Comers.” Translated by William Sharp. The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 2, Autumn 1895, pp. 60-71. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2018. https://1890s.ca/egv2_lerberghe_nightcomers/

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or are being used under fair dealing for research purposes , private study or education.