Homosexuality and Heretics in Baron Corvo’s “Stories Toto Told Me”

© Kelsey Brewis, Ryerson University 2018

“Stories Toto Told Me” and Progressive Themes in The Yellow Book

“Stories Toto Told Me” and “Stories that Toto Told Me” are two in a series of short folklore stories by English writer and artist Frederick William Rolfe, better known as Baron Corvo. These two tales are published in volumes seven (1895) and eleven (1896) of The Yellow Book. While both stories take on different subject matter, they are constructed using the same narrative framework, keeping the series consistent. Told by an Italian peasant boy called Toto through the lens of a seemingly older, more mature narrator referred to only as Sir, the stories themselves and the rapport between Toto and Sir are laden with underlying themes of both homosexuality and Catholicism.

“Stories Toto Told Me” from The Yellow Book‘s seventh volume is composed of two parts, told to the narrator from Toto’s perspective. “About San Pietro and San Paolo” is a folklore piece that details the construction of two churches that are being built for two rival Saints. “About the Lilies of San Luigi” focuses on the afterlives of two eccentric young Roman martyrs: San Sebastiano and San Pancrazio. Another young Saint, San Luigi, joins the martyrs in Heaven but is particularly put off by the fact that they are not as reserved as he. Both parts of “Stories Toto Told Me” are thematically explorative of the complexities of morality and ultimate justice. “Stories That Toto Told Me” from The Yellow Book‘s eleventh volume is also divided in two, “About the Heresy of Fra Serafico” and “About One Way in Which Christians Love One Another”. The stories in this volume are more personal and reveal more about Toto as a character, focusing more explicitly on Toto’s own relationships and intimacies while still remaining thematically consistent.

The inclusion of controversial themes like dissident sexuality and religion in the “Stories Toto Told Me” series is distinctly representative of The Yellow Book as a publication. The magazine characteristically did not place restraints on its contributors: for example, no word counts were enforced, female writers were encouraged to submit their works, and heretic content was rarely censored. For these reasons, The Yellow Book was critically considered to be a progressive publication for its time. Today, the magazine is a literary landmark of aestheticism and decadence. Scholars reflect on its emphasis on the complexities of topics like gender politics, in regards not only to homosexual themes, but to literary contributions from women writers such as Ella D’Arcy and Evelyn Sharp. Heather Marcovitch points toward the collection’s “. . .status as the first modern literary journal, its frank inclusion of early feminist and homoerotic writings, and its position as a catalyst for the complex network of writers, publishers and journalists” (Marcovitch, 86) as key elements that make The Yellow Book so markedly iconic today.

Frederick Rolfe and Homosexuality

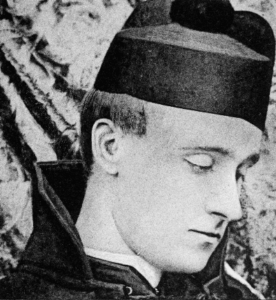

Though the “Stories Toto Told Me” series contains homosexual themes, it is of little importance in a literary sense whether or not Frederick Rolfe personally identified as a homosexual man. Brian Reade suggests that, in this context, it would be unwise to dwell on “personal transitions, only [on] the literary evidence of homosexual moods and . . . the idea of homosexuality as a romantic stimulus” (1). Aestheticism and homosexuality go hand-in-hand, even without personal connection. This is particularly evident in literature during the fin-de-siècle. Homosexual desires and homoeroticism in art and literature served as something of a means of expression for artists like Rolfe: “to be homosexually inclined thus became one of the secondary qualifications for declaring oneself an ‘artist’ . . . homosexual sentiment [is] part of the whole range of feeling which [waits] to be explored” (Reade, 31).

Frederick Rolfe expressed his own “range of feeling” through several different mediums: literature, paint, and photography among his favourites. It was during a photographic exploration in Italy that he met the peasant boy, Toto Maidalchini, that would inspire his “Stories Toto Told Me” series. He was fascinated with Toto and his friends, evident in the fact that they served first as Rolfe’s photographic subjects, and later as the central characters in one of his best-known works (Reade, 43).

Sexual Undertones in “Stories Toto Told Me”

It might be noted that Toto Maidalchini is described as being “beautiful leader of a group of boys with whom [Rolfe] spent the summer” (Parker, 43). Though it is not known exactly how old the boys in this group were, it is clear that both Frederick Rolfe and his implied fictional counterpart, “Sir”, are years their senior. The characters that Rolfe writes about in this series are usually adolescent boys.

The “Stories Toto Told Me” series provides within its stories an implicit literary commentary on the sexual climate that Rolfe would have experienced during the fin-de-siècle. There exists a common thread between the ideas of sin and the indecent exposure of the male body in more than one of Toto’s tellings. Arguably the most thematically explicit of the series are the stories in The Yellow Book‘s eleventh volume, those that revolve around Toto’s own experiences. For example, in “About One Way in Which Christians Love One Another”, Toto tells of an evening in which he nakedly creeps into a peach orchard in order to “enjoy [him]self” (Corvo, 158).

I ran away and enjoyed myself enough with the peaches belonging to those Capuccini. When I came home I dried myself with a cloth, took my shirt from under the seat in the porch, and went to bed again.” (Corvo, 158).

There is, in virtually all of the stories in the “Stories Toto Told Me” series, some mention of male nudity or indecency. In “About the Lilies of San Luigi”, San Luigi is evidently uncomfortable with the nakedness of the two martyrs. Interestingly, San Luigi’s character is described as having “not a bit of fun in him” (Corvo, 215). Rolfe’s writing often suggests that male nudity is representative of a carefree nature, of being happy and enjoying one’s life, while covering up is likened to being conservative and repressed.

Reflective Religion in “Stories Toto Told Me”

While Frederick Rolfe is known in literature primarily for writing fiction, much of his published work is either inspired by or reminiscent of his personal connections to sexuality and Roman Catholicism. Much of his writing is self-reflective, and transparently so. Each character that Rolfe writes appears to mirror him in one way or another. As A.J.A Symons suggests, “Rolfe dramatized the long misadventure of his life, and made real, on the plane of imagination, his defeated dreams and hopes” (Symons, qtd in Robinson, 81).

The “Stories Toto Told Me” series is composed of characters and situations that reflect the defining aspects of Rolfe’s personal life. For example, Toto’s nineteen-year-old brother Nicola is on his way to becoming a Catholic priest. Notably, Nicola struggles with balancing his religion and his implied homosexuality, often referring to himself as “a miserable sinner” (Corvo, 145). Rolfe himself walked a similar path, converting from the Christian Church of England to the Catholic Church of Rome. He claims that “at 25 [he] suddenly realized that, if it was ‘priesthood’ [he] was after, [he] was on the wrong road: the Church of England had nothing of the sort to offer [him], for she had nothing to do with Peter, and Peter had the key” (Rolfe, qtd in Robinson, 82). In “Stories Toto Told Me”, Nicola’s immoral, overtly sexual behaviour in school has deterred his path to priesthood. This is reflective of Rolfe’s own issues during his education that led first to his expulsion from college, and thus his failure to become a priest.

Toto’s character in the story is carefree in nature, representative of both innocence and lightheartedness. He is described by Jeffrey Parker as being “an example of unquestioning faith” (Parker, 44). In personality, Toto’s character serves then as the bright-sparked mirror image to Nicola’s depression. The brothers’ contrasting views on Catholicism and priesthood personify Rolfe’s own internal struggle with finding his religion.

Toto is variously described as an example of unquestioning faith, and uneducated peasant, and the triumph of oral tradition over literature.” (Jeffrey Parker, 44).

Fin-de-Siècle Sexuality in London, England

During the fin-de-siècle, not only was homosexuality considered immoral, acts of such were punishable by law. In 1533, King Henry VIII decreed that engaging in same-sex relationships was an “unnatural practice [whose offenders] shall suffer such paynes of death and losses and penalties of their goods chattles debts lands tenaments and hereditaments as felons” (Henry VIII, qtd. In Crozier, 61). In fact, it would not be until 1967 that acts of homosexuality were decriminalized (Crozier, 61) and longer still until same-sex love became socially acceptable. London, England, wherein The Yellow Book was published and Frederick Rolfe was born, served as something of a hotbed for homosexuality in the fin-de siècle: “[it] had long been associated with the city, and the link was reaffirmed in the 1880s and 1890s, a period when sex and relationships between men were the focus of particular debate and concern” (Cook, 33). As a backdrop, London was a progressive and exciting city. It was a passionate, artistic metropolis, diverse in both cultural and political landscape. It suggested an environment wherein one could develop “. . . a distinctive, secretive and in some ways insular homosexual identity” (Cook, 52). It was a particularly fitting place to create art for those whose work was thematically controversial, like Rolfe’s often was. As Cook suggests, London was “compelling for writers exploring homosexual subjectivity and subcultures, and the place of both within society. For the city was not only a place where ‘homosexual’ men congregated, it was also where the individual met a subculture and a subculture met society most intensely” (54).

Conclusion

The fin-de-siècle was a curiously progressive period of time, especially in literature and the topics discussed within it. The Yellow Book serves as a poignant representation of the era, a landmark collection of thematically progressive works of both art and writing. Within its volumes, The Yellow Book explores such taboos as dissident religion, heresy, feminism, and homosexuality unflinchingly.

Frederick Rolfe’s “Stories Toto Told Me” series is a visceral representation of the fin-de-siècle perspective, specifically in the context of dissident religion and sexuality. London, England, the city in which Rolfe was born and raised and in which The Yellow Book was compiled, was a prominent landmark for the creation of outside-the-box art and literature. Rolfe took advantage of the city as a place to explore and produce work that would not be filtered through such a conservative lens.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Works Cited

Cook, Matt. “‘A New City of Friends’: London and Homosexuality in the 1890s.” History

Workshop Journal, vol. 56, no. 1, January 2003. Scholars Portal, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/56.1.33.

Corvo, Baron. “Stories Toto Told Me.” The Yellow Book, vol. 7, 1895. The Yellow Nineties Online.

Corvo, Baron. “Stories That Toto Told Me.” The Yellow Book, vol. 11, 1896. The Yellow Nineties Online.

Crozier, Ivan. “The medical construction of homosexuality and its relation to the law in

nineteenth-century England.” Medical History (Pre-2012), vol. 45, no. 1, January 2001. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/229705633?accountid=13631.

Marcovitch, Heather. “The Yellow Book: Reshaping The Fin De Siècle.” Literature Compass, vol.

13, no. 2, 2016, pp. 79–87.

Parker, Jeffrey. “Frederick William Rolfe (Baron Corvo).” British Short-Fiction Writers, 1880-1914:

The Romantic Tradition. Gale, 1995.

Reade, Brian. Sexual Heretics: Male Homosexuality in English Literature from 1850 to 1900.

Routledge, 1971.

Robinson, Tim. “F. W. Rolfe: Defeated Man of Genius.” London Magazine, vol. 31, no. 11,

1992. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1299552590?accountid=13631.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.