A New Woman as a Feminist Princess in Laurence Housman’s “Blind Love”

©Paris Salmon-Wright, Ryerson University 2018

Princess and the Feminist Movement

I am curating Laurence Housman’s, “Blind Love” from the second volume of The Pageant (1894). I am interested in analyzing Housman’s character, Innygreth, and his portrayal of a New Woman, so that I can better understand the deliberate choice of Housman writing a fairy tale to inform readers of a political and social shift during the Women’s Suffrage Movement.

The Start

Fairy tales are not only bedtime stories from childhood. Writers have their audience analyze social issues comparing the fantastical context to reality. In “Blind Love,” Housman uses fantasy to focus on the limitations of female sexual expression. The princess, Innygreth demonstrates a power shift from the patriarchal figure of her father to herself. Her invisibility allows her to grow an independent and confident mind. Laurence Housman’s work and personal progress is inspired by the Women’s Movement (Housman, The Unexpected Years 223). Housman wants equality for women and to eliminate the patriarchy though his work (Doussot 142). The fairy tale genre usually receives a mass audience and is a way for writers to reinforce their ideas of how to question societal norms (Zipes 129). His feminist mission he is trying to voice can be seen throughout his character creation of Innygreth.

What Are We Arguing?

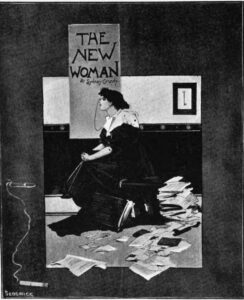

Innygreth is an example of a New Woman. Housman creates her character to empower the female voice. Laurence Housman uses the fairy tale genre to reach an audience to provoke and inspire his feminist agenda for the necessity of equality for women. He portrays Innygreth as a New Woman while using the fantastical element of invisibility to focus on her intellect and confidence rather than her beauty. Her intelligence and dialogue disturb the norms of a princess due to her involvement of protecting and saving herself rather than waiting for a prince. Innygreth inspires female readers to break domestic gender roles ingrained in society. First, Innygreth outsmarts her father and disobeys his wishes because she focuses on her personal development. Second, Innygreth’s life is based on sexual desire and her confidence has her use sexuality to save her partner and become in control of her sexual expression. Lastly, Innygreth has many qualities of what a “New Woman” appears to be instead of the portrayal of a typical princess, she is a woman who is capable of being independent.

Blind Love Recap

“Blind Love” follows the king, Agwisaunce and his cursed child, Innygreth. A fairy tries to seduce the king, however his loyalty to his wife has him reject her. She puts a spell onto his first-born child that would make her invisible until she makes love to a partner. Innygreth finds herself falling in love with her father’s lieutenant, Sir Percyn, who is not an ideal candidate in the eyes of Agwisaunce. He is fearful of his daughter becoming impure and sends Sir Percyn to prison where he is sentenced to death. The king tries to lock the rooms in the castle, so Innygreth is unable to sneak out to find her true love. However, her invisibility allows her to pass the guards where she visits Sir Percyn. She decides to protect him by using her invisibility as a shield. They eventually make love and the spell is broken. Once the king realizes she is visible, he becomes enraged witnessing the impurity of his daughter. However, she persuades her father to marry Sir Percyn and they happily wed.

Innygreth vs. Agwisaunce and the Patriarchy

Women’s rights are an ongoing battle for equality. The 1890s is when the New Woman launches an attack on the patriarchy (Oakley 42). Innygreth never fully attacks her father, however she makes subtle remarks which questions his authority. Innygreth’s invisibility is able to give her an independence which distances herself from princess duties because her beauty is never up for debate. She is able to move around the castle and witness interactions that allows her intellect to flourish and she says, “… I learn things as they are, and not as princesses are used to be taught them. I know many things that you do not. Some day when I know more I will teach you to govern well” (Housman, “Blind Love” 67). Through her education, she is able to make decisions without needing to please her father. This ideology for a woman is seen as a threat in the Victorian era because critics believe women who are uneducated with minimal role models will see the New Woman and become this type of woman (Dowling 54). Innygreth understand the unequal relationship between her father and herself. She tries to provoke him by being out spoken instead of silently nodding. Her approval comes within herself, not by her father.

There is a tension between the masculine figure and the New Woman. Men fear women’s equality would take their power away, when in fact, they would only be equally viewed in a societal context. Innygreth wants Sir Percyn as her lover, “Innygreth’s mind was at ease, and she had full confidence that her power should work her lover’s release; and as for marriage, she knew that in the end she was her own mistress” (Housman, “Blind Love” 75). She is in complete control of her choices and this threatens the power of the king. In fairy tales, the purpose of the genre is to create an alternative world that demonstrates a reality outside of current societal norms that demonstrates the, “acceptance of otherness” (Doussot 143). Housman has his audience question women’s current role in the 1890s by using the relationship of the king and his daughter to relate to the hierarchal relationship men have over women. The fantastical element gives Innygreth her confidence to overpower her father by concentrating on her confidence instead of her beauty.

Promiscuous Innygreth and the New Woman Sexuality

Women’s sexuality can be a controversial conversation depending on how one views their comfort levels with intimacy. In the 1890s, critics to the New Woman believes she will, “threaten the vital bonds of state and culture” (Dowling 50). For women to be in control of their sexual expression means sex is going to be seen as an equal act for men and women, instead of only for reproductive purposes for the woman. Those who disapprove of the New Woman argues how the she may “compromise” her gender and class because the freedom can be a toxic example for women to admire (Dowling 54). Housman uses “Blind Love” to people who are unable to confirm to societal norms and explore their individual path (Doussot 143). The New Woman is a danger to society because she gives women a voice to go against the gender norms and pursue education and personal desires instead of domestic values.

From Housman’s character choices of Innygreth, he portrays her in the eyes of her father, “already she goes the way of a wanton… and that is a short road with a quick ending. Though walls have ears, for her they have not eyes (Housman, “Blind Love” 75). Innygreth is not going to stop because her father demands it. She wants to explore her relationship with Sir Perycn and uses her curse to her sexual advantage. Fairy tales allow readers to question societal debates regarding social conflicts, such as gender and sexuality, to be explored in an unnatural setting with realistic dialogue (Zipes 15). To further the tension between her father and Innygreth, he hears, “… the sound of one climbing the wall without, and presently kisses so many and passionate that, fearing what might have place, he leapt forth, crying out on his daughter for a wanton” (Housman, “Blind Love” 74). This is an example of how Innygreth uses her sexual consciousness to explore her intimate relationship with herself and her lover. Even though they have not made love yet, the teasing goes for her pleasure instead of properly behaving under her father’s orders (Dowling 52). Innygreth is not only challenging her father’s power. Moreover, she is also exploring sexual boundaries that are unmentioned in daily conversations.

Innygreth and Sir Percyn have a “romantic legacy” like fairy tales in the Victorian era (and previous centuries) suggest by ending up happily wed. Moreover, Housman gives another dimension to New Woman by using Innygreth in a heterosexual relationship (Sumpter 226). Not only is Innygreth sexually promiscuous in terms of the late-Victorian era, she is always in charge of her personal decisions. Through her fear of Sir Percyn’s death, she uses her sexual desire instead of contemplating the possible future, “her light she put away for often the shuddering in her hands might not hold it; but her lips gave no sound of her sorrow” (Housman, “Blind Love” 76). Through her shaking and worried state, she desires to only experience fond moments with Sir Percyn and chooses intimacy over her possible loss. Housman writes on women’s freedom and emphasizes new roles in society for women (Oakley 78). Innygreth is not only intelligent or a sexual deviant, she has multiple layers to signify the multi-dimension she has as a woman. Housman uses the strengths of her character to portray a woman who has the ability to overpower the patriarchy while being sexually expressive. Innygreth creates a different perspective for gender roles regarding women and sexual restrictions. To discuss intercourse violates the, “polite norms of Victorian realism” by distorting how sex compares in reality to literature (Dowley 52). By analyzing Innygreth’s sexuality in terms of the late-Victorian context, Housman allows readers to see how Innygreth might create controversy within the society. He writes on sexuality to have his readers become uncomfortable with the explicit sexual content because of how silenced sex is in daily conversations.

Innygreth vs Herself

There is a significance of the invisibility because Housman uses it symbolize the importance society places on beauty standards by erasing it. Innygreth is never a target for her beauty and does not appear to have insecurities, “therefore she was honest without confusion, and had modesty without fear; and having had no shame for her own body since the day of her birth, had no shame of it in others” (Housman, “Blind Love” 68). Critics of the New Woman are skeptical of women being “radical” since it might create a “social apocalypse” which may lead women to being unfit for domestic roles (Dowling 57). Innygreth allows readers to view the role of a princess in a different perspective because she is given emphasis to be a three-dimensional character, instead of being limited to love and her appearance.

The Women’s Movement is established in the eighties and continued to gain momentum throughout the nineties and the turn of the century (Oakley 73). Women are exposed to role models who are fighting for their independence are labelled as the New Woman (Oakley 73). From the independence Innygreth gains as she grows older, “slowly her mind grew in gentleness and grace of her own choosing” (Housman, “Blind Love” 67). Throughout the story, the reader sees the development of Innygreth and how she is able to become her own character. Fairy tales are written in the 1890s wrote about controversies within the decade and challenges these ideas, specifically of identity and beauty (Sumpter 225). The fin-de-siècle period is a time of revolt against the established culture to change ingrained societal norms and to create a society that goes beyond the culture (Dowling 60). The New Woman is only a fraction of the norms that are changing in this period and Housman uses his artistic abilities to prove his devotion to women’s equality through his interpretation of Innygreth.

Conclusion: How Innygreth and her Relation to Laurence Housman

Overall, “Blind Love” is a fairy tale written for women to admire Innygreth’s voice and to give them inspiration to speak for themselves. As the years went by, Laurence Housman becomes involved in the Suffrage Movement which changes Housman’s work further for women and loses friendship when they do not believe in the progression of women’s rights (Oakley 70). Innygreth is not going to be the last feminist character Housman would write, he will further explore through the peak of his activism in 1907 and 1908 with his sister, Clemence, where they would take part in conferences and use their creativity in the Movement (Oakley 71).

Innygreth’s invisibility is not a curse to her in the end, as she is able to thrive. It can be said that there is a lesson within fairy tale and fantasy literature, “… we are all misfit for the world, and yet, somehow we must all fit together to survive” (Zipes 153). Housman writes a New Woman who is deemed as a misfit in terms of trying to create new roles for women in society. Innygreth is simply another character to fit the story, just as the New Woman mold fits into society by creating a voice for those who are silenced. Everyone wants to survive; however, some need to fight harder to survive with their limited access to human rights. Misfits need a voice and Laurence Housman brings support to female readers by promoting his alliance to the new wave of women in society.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Works Cited

Doussot, Audrey. “Laurence Housman (1865-1959): Fairy Tale Teller, Illustrator and Aesthete.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens, no. 73, April 2011, pp. 131-145. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/878055251?pq-origsite=summon.

Dowling, Linda. “The Decadent and the New Woman in the 1890s.” Reading Fin-De-Siècle Fictions, Addison Wesley Longman, 1996, pp. 47-63.

Housman, Laurence. “Blind Love.” The Pageant, vol. 2, 1897, pp. 64-81. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Center for Digital Humanities, 2018, https://archive.org/stream/Pageant1897#page/n101/mode/2up/search/Blind+love.

Housman, Laurence. The Unexpected Years, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1936.

Oakley, Elizabeth. Inseparable Siblings: A Portrait of Clemence and Laurence Housman. Brewin Books, 2009.

Sumpter, Caroline. “Innocents and Epicures: The Child, the Fairy Tale and Avant-Garde Debate in Fin-de-Siècle Little Magazine.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, vol. 28, no. 3, September 2006, pp. 225-244. Scholar Portal, https://journals-scholarsportal-info.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/details/08905495/v28i0003/225_iaetctadiflm.xml.

Zipes, Jack. Why Fairy Tales Stick: The Evolution and Relevance of a Genre. Routledge, 2006.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.