Fantasy as Feminist Critique in Olivia Shakespear’s “Beauty’s Hour: A Phantasy”

Noah Holder, Ryerson University, 2018

The Author, Their Work and Its Capsule

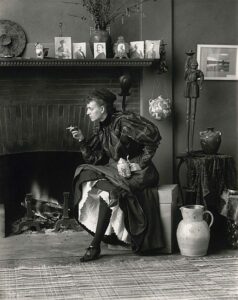

Olivia Shakespear was born Olivia Tucker and married Henry Hope Shakespear, a solicitor, in 1885 (Figure 1). Shakespear’s work was heavily influenced by her friend John Oliver Hobbes which is a pseudonym for Pearl Mary-Teresa Craigie. Craigie had problems with alcohol and medication abuse; however, Shakespear mostly drew inspiration from her life as a briefly married woman who was divorced by her husband.

Olivia Shakespear uses her modern short story “Beauty’s Hour: A Phantasy” (1896) as a feminist critique through the use of the fantastic by redefining womanhood and femininity in the 1890s. As the fin-de-siècle served as a prelude to feminist movements, a new representation of femininity began to arise in fin-de-siècle literature. Shakespear’s fantasy finds itself in both vol. 4 & 5 of Leonard Smithers’ The Savoy. Shakespear found herself as only one of two women writers within the little magazine (Fig. 2). The Savoy was a literary magazine named after a British hotel known for homosexual scandals. Artists like Oscar Wilde would frequent the hotel for rendezvous. Social deviance was at the root of the magazine, for example, Aubrey Beardsley who was ousted from The Yellow Book, after rumours of being associated with Oscar Wilde, joined The Savoy. The pairing of Beardsley and avant-garde artist Arthur Symons solidified the ethos of the magazine and due to The Savoy’s subject matter it is no surprise Shakespear’s work is found among the literary contents.

Fantasy in fin-de-siècle

Nineteenth century literature did not use similar generic terms found in modern 21stcentury literature. Therefore what is known as fantasy in modern western society, would have been categorized under a different name. Nicholas Ruddick, in his article “The Fantastic Fiction of fin-de-siècle”, outlines the application and meaning of the term fantasy. Ruddick explains that in the nineteenth century the genre of romance was mostly fiction involving “…magical, supernatural and other non-realistic elements”, and to avoid confusion with taxonomical language of today Ruddick uses the term fantasy in place of romance (189). Using Ruddick’s understanding and definition of fantasy it can easily be used to categorize Shakespear’s work as fantastical. Fantasy allows Shakespear to create a text with magical elements to alienate it from the reality of nineteenth century Britain, and recreate a quasi-British society. In doing so a nineteenth century audience can still identify with the society portrayed within the text, due to common 1890s customs, references, etc. and notice Shakespear’s critiques through the ethereal.

Mary Gower’s Hour of Beauty

Shakespear’s short fiction piece follows the life of Mary Gower as she self-narrates her few days with transformative powers. Mary is a working woman, a secretary for one Lady Harman. Mary describes her “…own face…with no salient points to make it even impressively ugly… [she has] neither eyelashes or distinction…[and] her figure is not worthy of the name…” (Shakespear 12; ch. 1). Later in the evening Mary is home, in front of a mirror, she suddenly witnesses herself disappear from the mirror and reappear as a gorgeous, slender woman, a woman she will eventually name Mary Hatherley. 1890s artist had many times depicted Victorian women looking upon themselves in mirrors, Shakespear’s fantasy creates a magical element from a trend found in fin-de-siècle painting (Fig. 3). By doing so Shakespear manipulates Late-Victorian reality adding the supernatural to a common art practice. With Mary’s landlord as her witness, she had become the exact physical opposite or herself, she was now beautiful.

Mary’s character is a free-minded woman, using both narration and speech she questions the patriarchal norms that pose as boundaries to the possibilities of femininity. She understands the power that beauty holds within her society but does not wish for it to be the only time a woman finds herself with an inkling of agency. It is Mary’s disdain for her current reality of womanhood that she finds herself portraying the role of a New Woman, continuing to challenge the gendered boundaries of fin-de-siècle Britain. Mary Gower is the exact type of woman that caused Late-Victorian Britain anxiety.

New Woman as a Critique

Shakespear’s fiction is coming at the end of the Victorian era. An era of decadence and anxiety. Britain was caught between the possibility of losing a Victorian Britain and the fear of what was to come post-nineteenth century. Movements such as Women’s Suffrage was emerging and feminist discourse was being found in literature all over Britain. Feminist authors such as Vernon Lee, Sarah Grand and others began producing fiction disseminating a feminist ideology, as well as essays discussing the Woman question.

The term New Woman was coined in 1894 by Sarah Grand, it represented the possibility of a new feminine identity. The New Woman was working class, a smoker, a drinker, a woman who welcomed sexual liberation, fought for dress reform and opposed marriage (Mumford 539)(Fig. 4). In other words, a woman who readily questioned the gendered boundaries of her reality. Mary Gower was Shakespear depiction of a New Woman, Mary is a critique of her society and the reality she experiences. “’But what of the woman behind the face?” Mary asks this of Gerald, and it is a question she continues to explore throughout the text.

The New Woman in literature was an opportunity for women writers to redefine femininity. As Ruth Robbins discusses in her article “Vernon Lee: Decadent Woman?”, the issue with female representation in literature is that most women characters are created from a man’s imagination (147). Despite the presence of women in literature, during the nineteenth century men still dominated the industry. As a result, there is an overwhelming amount of misrepresented women, women eager to marry, devote to their family and tending to homes above all other things. These representations marginalized women by continuously perpetuating patriarchal definitions of womanhood.

Shakespear, much like many fin-de-siècle women writers, seizes the opportunity to create an emancipated representation of womanhood through her protagonist. Mary as both of her identities, challenges the 1890s ideologies of femininity. Mary attends a dance under her magical disguise, she meets Gerald, in conversation Mary goes on discussing the idolization of the beautiful woman, opposing the thought that “’The Face is an indication of the soul…’” as Gerald professed. By the end of Mary’s diatribe, she notices that “…Gerald sat looking at [her], with a rapt gaze, but [she] saw that he had not listened to a word…” (Shakespear 24; ch. 4). This lack of respect stems from the marginalizing belief that women are passive, doting and meant to maintain a household. Women were not yet believed to be able to entertain discourse, let alone offer revolutionary social criticisms. Mary’s battle is with being treated equally and being able to do what a man can do without being ignored, or scoffed at. As Ruddick discusses, men in fin-de-siècle Britain opposed the idea of the New Woman because they felt threatened by a well-educated, freethinking woman (193).

Mary Gower and Mrs. Grundy

Mary’s estranged approach to her reality does not only see her in contention with men, but also other women as well. In conversation with Betty and Claire, two beautiful women Mary speaks of, Mary mentions that passion for anything is not needed in a pretty woman to which Betty replies “’Oh…Mary! Always finding fault with pretty women.” (Shakespear 12; ch. 5). Mary goes on to say that she is not finding fault in women themselves but “’…with the world,’”, because men have held beauty so highly women find themselves jealous of each other (Shakespear 12; ch. 5). Mary’s conversation with the women portrays conflicts within feminist fiction and New Woman in society.

Mrs. Grundy is the British ideal for the perfect Victorian woman who’s narrow minded and prude (Ruddick 192). Mary finds herself, a New Woman, surrounded by women who perpetuate the male imagined Victorian woman (Fig. 5). During the fin-de-siècle, feminist fiction met resistance by anti-feminist writers, there was a “…consensus among traditionalists…. that ‘Nature’ designed woman to marry, have children and preside over a happy home.”, this left no space for women to be free of thought (Heilmann and Sanders 290). Heilmann and Sanders explore woman writers, both feminist and anti-feminist, in fin-de-siècle Britain in their article “The rebel, the lady and the ‘anti’: Femininity, anti-feminism, and the Victorian woman writer. This intra-gendered conflict is represented in Shakespears’ work through representing Mary as the sole New Woman surrounded by countless women who represent the dominant Victorian Ideal. Mary, at one point in the text, is literally surrounded at the dinner table by both men and women who represent the hegemonic, misogynistic ideals of the Late-Victorian era.

Conclusion

It is important to note that the New Woman and feminist fiction movements took place in a vacuum of time. Magazines have the opportunity to capture a moment, and with that comes all of an era’s issues and new developments. 21stCentury literature and society has come a long way in the hegemonic idea and representation of women but, still similarities can be found. Sexual liberation is still controversial topic in both 19thcentury Britain and 21stcentury popular culture. With that being said, “Beauty’s Hour: A Phantasy”, along with other feminist fiction, is a representation of the transformative power of literature. Through New Woman portrayal in fiction, and women writers reclaiming representation of themselves through texts, the marginalizing depiction of woman was torn down.

Inconclusion Shakespear uses fantasy to comment on fin-de-siècle Britain and its idea of femininity. As John Goode analyses in his article “Writing Beyond the End”, he emphasizes that texts look ahead to evolve or overthrow the ideas of the present (16). By creating a pseudo-British society that alienates itself from 1890s reality through the use of the supernatural. This allows Shakespear to critique British culture without directly depicting it, contributing to countless works aspiring to transform fin-de-siècle society. Literature like Olivia Shakespear’s and other New Woman writers began the discourse of what a post-Victorian woman could consist of. Literature has the ability to push society forward as it continues to evolve sparking change in those that identify with literature’s plot and characters.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Works Cited

“Feminism.” and “New Woman.” Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Garland, 1988

Goode, John. “Writing Beyond the End.” Fin de Siècle/Fin du Globe: Fears and Fantasies of the Late Nineteenth Century, edited by John Stokes, Macmillan, 1992, pp. 14-36

Heilmann, Ann. Sanders, Valerie. “The rebel, the lady and the ‘anti’: Femininity, anti-feminism, and the Victorian woman writer.” Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 29, 2006, 10.1016/j.wsif.2006.04.008. Accessed 14 October 2018

Ledger, Sally. “The New Woman and feminist fictions.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle, edited by Gail Marshall, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 153-168

Shakespear, Olivia. “Beauty’s Hour: A Phantasy.” The Savoy, Aug. 1896. Vol. 04, pp. 11-24

Shakespear, Olivia. “Beauty’s Hour: A Phantasy.” The Savoy, Sept. 1896. Vol. 05, pp. 11-24

Robbins, Ruth. “Vernon Lee: Decadent Woman?” Fin de Siècle/Fin du Globe: Fears and Fantasies of the Late Nineteenth Century, edited by John Stokes, Macmillan, 1992, 139-161

Ruddick, Nicholas. “The fantastic fiction of the fin de siècle.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle, edited by Gail Marshall, 2007, pp. 189-206

Disclaimer: Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.