Catholicism and Lack of Decadent Art in Graham’s “The Christ of Toro”

©Marina Arnone, Ryerson University 2018

Introduction

Mrs. Cunninghame Graham’s “The Christ of Toro” was published in volume 13 of The Yellow Book (April 1897). The Yellow Book was pitched to Elkin Matthews in 1894 by Henry Harland and Aubrey Beardsley. The magazine was intended to have an experimental take on writing and visuals. The avant-garde style encouraged much backlash from society through the inclusion of taboo concepts and ideas. Harland and Beardsley wanted The Yellow Book to be viewed as a modern magazine, which was true until 1895 when it was identified as having a more conservative approach. Aubrey Beardsley, who was directly connected to decadent artwork, was removed from his role of art director in 1895. This happened before the 13th volume including “The Christ of Toro” was created. Therefore, the later years of the publication, specially the 13th volume, began to move away from the decadence movement. Mrs. Cunninghame Graham, also known as Gabrielle de la Balmondiere, was an author widely recognized for her work on biographies and folklore stories. She contributed “The Christ of Toro” to the 13th volume of The Yellow Book.

“The Christ of Toro” was divided in to two sections entitled “The Prediction” and “The Fulfilment”. The first section introduces the reader to Brother Sebastian. Brother Sebastian joined a monastery in the small town of Castile. One day the Brothers began to notice a change in Sebastian. He had begun painting artwork in his cell, at the knowledge of the Prior who believed he should embrace the talent God blessed him so generously with. Although the men got backlash from Brother Matthias, the Prior thought the painting was so pure and holy and decided to hang it at the highest alter. Eventually as time passed the painting was moved from the centre of the alter to the far back corner. In “The Fulfilment” Graham introduces the reader to Juan. Juan is spoiled by his parents which ultimately leads him to be very rebellious and selfish. Eventually his mother and father die, and he is given a chest by his father to be opened when he had nothing left to live for. Juan finally hit a low point and decided to open the chest. Inside was a noose. Juan decided to kill himself in the Locutory of the Augustinian Friars, to spite his father. This is where he saw Brother Sebastian’s painting in the far corner of the wall. The picture captivated him and Jesus walked out of the canvas towards him with open arms. Jesus told him that his sins would be forgiven if he could go forward and live a life of holiness. He did this and became Fray Juan de la Misericordia, a man of selflessness. The painting was eventually moved back to the high alter and acted as a central figure of guidance and strength to the people of Toro. Although The Yellow Book is closely associated with the decadent movement, Mrs. Cunninghame Graham’s “The Christ of Toro” shows that, by the thirteenth volume at least, the magazine began to include elements of Catholicism through legends of the miraculous.

Decadence and Faith Connected to The Yellow Book

The Decadent Movement was a time categorized in the 1890’s through its experimental and sensual pieces of writing and artwork. The Yellow Book was associated with this movement largely due to Beardsley’s work as the art director. His decadent artwork ceased in volume 4, January 1895, and “Christ of Toro” was published in April 1897, in volume 13. Therefore, the magazine still contained decadent elements but began to move towards Catholicism trough legends and the miraculous.

According to Beckson, the 1890’s should not be associated with yellow but rather with white. He alludes to this idea because white is associated with purity and decadent artist were drawn to Catholicism because it contained a sense of purity. This is evident in “The Christ of Toro” because Graham decides to focus on spiritual elements. The story is centred around the monastery. This is where Brother Sebastian creates the painting that will go on to inspire the conversion of Juan in to purity and sainthood. Decadent artists were also attracted to the concept of mortality and scandal. This is true in “The Christ of Toro” as Juan is presented with a noose by his father. This would have been shocking for a reader in the 1890s as suicide was a taboo. Therefore, it was interesting for decadent artists to include elements that were present in society, such as a great influence on Catholicism, with something that would have been shocking and scandalous, such as Juan wanting to commit suicide in the Locutory of the Augustinian Friars. Decadent artists commanded attention by attempting to transform their lives into art in an attempt to make man less human (Beckson XLIV) and would rely heavily on sensation, mystical language and a tortuous style. Mrs. Cunningham Graham alluded to this idea by creating Brother Sebastian and Juan as very complex characters. Decadent artists were attracted to the dark side of experience and this is also evident in both characters. Brother Sebastian is portrayed as a man who struggled to find purpose in his life. He experienced much sadness in his life before he finally joined the convent. This is where he was finally able to find his purpose and flourish in his artwork. Graham also portrays Juan as someone who struggles with his own identity, therefore leading him to rebel and lack confidence. Juan ultimately finds himself, as Brother Sebastian did, through the working of the church and art. This alludes to the ultimate idea of decadence and its portrayal of complexity within writing and art.

What Art Means in the Decadent Movement

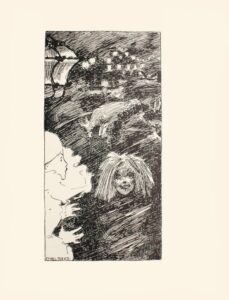

Artwork in the Decadent Movement proved to be outlandish, often erotic and grotesque. A leading pioneer in this type of art was Aubrey Beardsley. He was the art director of The Yellow Book until 1894 when he was fired from speculation that he was involved in the Oscar Wilde arrest and trial. For many years he contributed to the overall theme of the magazine as being experimental and shocking to the conventional. After his dissolvement, the magazine, although still closely aligned with decadence, began to focus more on the enlightenment and purity of Catholicism. As “The Christ of Toro” was published after Beardsley had left the publication, the portrayal of artwork can be seen as being further away from the movement. Artists in the decadent movement often would experiment with changing forms of art and would fully explore dimensions of their emotions to create shocking pieces of art (Knight 3). Matthew Lockerd alludes to the idea that artists of this movement were drawn to Catholicism, “According to Hanson, the Church was both the source of a complex “dialectic of shame and grace”, and “a beautiful and erotic work of art, a thing jewelled over like the tortoise that expires under the weight of its own gem-encrusted carapace in À Rebours” (Lockerd 145). He introduces the idea that decadence artists were interested in emotions and sensibility, often from a dark in-depth perspective. Therefore, by the end of the movement these artists began to transition from this to looking at the complexity of shame and grace and how this is presented in the church. “The Christ of Toro”, especially through the concept of retelling a folktale, directly contrasts art from the decadent movement.

What Art Means in “The Christ of Toro”

The “Christ of Toro” is the telling of a Catholic folktale. It is the story of how a painting was transformed to have mystical elements that ultimately led a sinner to God. Brother Sebastian grew closer to God through the painting of his picture. It gave him the purpose he never felt he had. Juan had this same experience as the painting spoke to him when he had nothing left to live for. Juan was ready to commit suicide when the painting captivated him. Jesus walked out of the painting with open arms and told Juan to go forth and live a life devoted to him. Therefore, the painting worked to bring both men closer to God which would have been the ultimate goal for people in the 1890s. Matthew Lockerd encourages the idea of decadent artist, like Beardsley, moving away from decadence, “Eliot and his decadent precursors, including Beardsley, share a ‘curiously similar’ turn away from art that dwells on personal ‘distortions’ and haunting ‘nightmares of vulgarity’ to traditional religions that provide new ‘color’ to their work and a ‘haven” for their souls” (Lockerd 145). This concept directly connects to the article as Graham was of the time that was moving away from dark and heavy literature and artistry. Therefore, her introduction into Catholic folktale prove to be of the new attitude and tone of the 1890’s. “The Christ of Toro” is considered folklore because it has characters and a plot, as well as it has a central theme, which revolves around Catholicism. It is also considered a legend because it alludes to El Toro and it creates its own religious story that can be passed on and retold. El Toro in Menorca was named after the bull that lead the monks up the hill to the highest peak. It is here that the monks were faced with a statue of the Virgin Mary chiselled in the rock. The monks built a monastery in this spot around 1670 which remained until 1835 when church property was taken away. Eventually the monastery was destroyed in the Spanish Civil War in the mid 1930s and rebuilt at a later time. This information is relevant to the story as it shows the emphasis of religious miracles, specially spread through traditional stories, during this time period. The emphasis on religious legends, as well as the contrast of art ultimately work to move the story further away from the decadent movement.

Conclusion

“The Christ of Toro” in The Yellow Book demonstrates that although closely related to decadence, Graham introduces concepts of Catholic legend that furthered her story from the movement. The decadence movement was a time in the 1890s that categorized artists and writers who wrote using emotion and sensuality and would often look at the darker side of each situation. The Yellow Book began to move away from the decadence movement when Aubrey Beardsley was replaced as the art director in 1895. He was best known for his art work containing grotesque and shocking imagery. “The Christ of Toro” revolves around the power of art, specifically the painting that Brother Sebastian produced. The artwork was not one of decadence but rather had bright colours and intricate details of Jesus. The artwork helped Brother Sebastian and Juan move closer to faith. This directly contrasts the decadence movement as it put emphasis on purity and change, rather than torture and sadness.

Works Cited

Balmondiere, de la Gabrielle. “The Christ of Toro.” The Yellow Book, vol. 13, 1897, pp. 56-73.

Beckson, Karl. “Introduction.” Aesthetes and Decadents of the 1890s, edited by Karl

Beckson, Academy Chicago Publisher, 1993, pp. XXII-XLIV.

Cevasco, A. George. The Breviary of Decadence. AMS Press New York, 2001.

Hanson, Ellis. Decadence and Catholicism. Harvard University Press, 1997.

Knight, Frances. Victorian Christianity at the Fin de Siècle: The Culture of English Religion

in a Decadent Age. I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2016.

Lockerd, Martin. ““A Satirist of Vices and Follies”: Beardsley, Eliot, and Images of

Decadent Catholicism.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 37, no. 4, 2014, pp. 143–165.

Images in this online exhibit are either public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purpose of research, private study or education.