Breaking Down the Binary in “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” by Vernon Lee.

© Copyright 2018 Sarah Ali, Ryerson University

Introduction

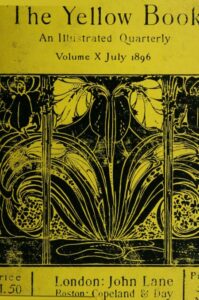

“Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” by Vernon Lee is a short fairy tale of the fin de siecle. It was published in July 1896, in Volume 10 of The Yellow Book, a quarterly British literary periodical published in London from 1894 to 1897. The story explores the regulation of women under Victorian patriarchy through the metaphor of a hybrid woman, half snake-half human, who is trapped in art. Confined within a magical tapestry, and the hybrid body of a snake, the female searches for release from her confinement.

Fin-de-siècle Britain

Late nineteenth-century Britain was a time of significant upheaval as modern culture sought to divorce itself from antiquated moral notions of living. Victorian morality was in a state of crisis as society tried to liberate itself from what was thought of as dogmatic religious beliefs no longer able to sustain a rational society as it evolves through material progress (Xiao 1815). New ideas were explored through art and literature. Contempt for the old order was reflected in the desire to rescue art from moral judgment and use it as a form of resistance against the dominant culture.

The Rise of the Aesthete and the Decadent

Aestheticism and Decadence are the two defining movements of the time. While an aesthete was dedicated to the expression of beauty and to pure aesthetic satisfaction itself, the decadent goes a step further and asserts itself through an active attack and rejection of prevailing culture and any moral judgment (Cohen, 214-215). The aesthetic and decadence movements of the 1890s thus defined the fin-de-siècle as an age of transformation. Prominent writers associated with these movements are Oscar Wilde, Charles Baudelaire, Henry Harland and others. The fin de siècle, relatedly, gave rise to the supernatural phenomenon in stories, especially in stories by women writers, who used it as a way to explore covert female desires considered dissident and unnatural under Victorian patriarchy (Liggins 37). This was their act of resistace against the overwhelming patriarchy of their time. “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” is such an example of the supernatural phenomenon in 1890s women literature.

Fairy Tales: A Medium of Change

Lee’s story employs the supernatural element in her story through the fairy-tale genre. The fairy-tale genre, similar to the ghost stories of the fin-de-siècle, became a conduit for the expression of the social injustices of the time. As a genre, it went through a series of rebirths and assumed a central position in matters of radical social debates that characterized much of the fin-de-siècle. Writers marginalized due to their gender or sexual preferences used it as a means of expression of ideas of the enforced ‘otherness’ of their social experiences (Sumpter 88). Infantilized and silenced to fit in the mold of the subservient gender, for the Victorian woman writer and reader who was perceived as intellectually inferior to man, Vanessa Dickerson comments that the supernatural element served as a medium to explore their ambiguous status and express their hidden desires (8).

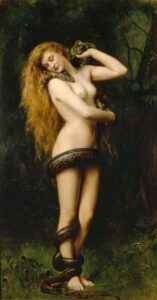

Damsel in Distress: With a Twist

Lady Oriana, in the story, is the quintessential damsel in distress but with the twisted logic of being a hybrid creature. Alberic the Blond rescues her but fails to fulfill the conditions of the curse which require him to be faithful to her for a period of ten years. She, therefore, cannot escape the curse of being a snake. The hybridity of Lady Oriana as a ‘half-snake, half-fairy’ female in the story is not only physical, but also logistical, spatial, historical, and cross-generational. She is first made apparent through the tapestry in which she exists as a mere object of art. She fills the empty spaces of Prince Alberic’s childhood imagination and fancies and occupies his dreams and thoughts as he grows into adulthood. She traverses through history and time, through myth and lore, using the story-teller as a medium. She is known by both Prince Alberic and his ancestor Alberic the Blond. Her hybridity is the symbol through which the castrated and mutilated identity of the Victorian woman is exposed and the metaphorical representation of the female struggle for liberation against patriarchal subjugation.

Snakes as objects of Moral Interest

Concerning representations of the snake body in Victorian art, Alison Smith asserts that the snake in artistic presentations can be viewed as a metaphor that could project and expunge social and subjective anxieties surrounding the body. She states that

“Interest in the snake as symbol, with its connotations of malignancy, vitality and

sin, had a rich lineage in literature and art, and in the realm of aesthetics, serpentine

configurations had long been utilised for purposes of mesmerising and repelling the

eye, delineating the perimeters of human beauty as well as deviations from this ideal (151)”.

The tragic fate of Lee’s Snake Lady explores how the assumed ‘other’ can be stigmatized and appropriated to serve the dominant agenda, in that, the Snake Lady is murdered because snakes represent evil magic. Lee portrays the snake as inherently good and harmless in the story and therefore creates a sense of injustice which twists the logic of good and bad. Juxtaposed against the vainglorious Duke and his scheming co-conspirators who want to control Prince Albert, the Snake Lady is gentle, generous to the Prince, nurturing, and dignified in character. The ‘other’ becomes desirable. This subversion ats as a lens through which Lee questions the repressive and unnatural act of the social policing of women and the erasure of their sexuality and intellect.

The Moniker of Vernon Lee

Vernon Lee was the name under which Violet Paget wrote her short story in The Yellow Book. Already an established writer and philosopher, Lee had penned a variety of psychological ghost stories before this publication in The Yellow Book (Denisoff and Kooistra). She was a woman of ambiguous sexual orientation whose private and public life assumed complicated and at times contradictory stances on the sexual politics of the late Victorian era (Kandola). It is of significance that Lee’s sexual orientation was a dire contradiction to the ideal Victorian woman whose sole purpose was serving the home and the husband and reproducing. This contradiction is therefore reflected in her changing politics, her writings, even in the choice of the male moniker as the author of this story. Vernon Lee stood in for Violet Paget to tell the story of a hybrid female creature who is trapped, operates in secrecy, denounced as evil despite no wrongdoing, and ultimately eliminated. The hybridity that Paget had to assume to tell this story as well as the hybridity of her life as a sexual other in the Victorian milieu is characteristic of a member of a society that feels policed. It tells the story of the many fringe groups of Victorian society who did not fit under the umbrella of the strict Victorian morality.

Prince Albert and the Snake Lady: An Overview

Abandoned to the care of servants since childhood, Prince Alberic who is raised in seclusion has valued one thing above all. A tapestry in his nursery depicting his ancestor Alberic the Blond and the Snake Lady. A traveling story-teller narrates to him the legend behind the tapestry. Once shipwrecked on a strange land, Alberic the Blond stumbles upon a magical castle where he receives every hospitability imaginable. There he encounters an inscription that tells the story of the captured fairy Oriana who has been cursed to be a snake. The curse will be broken if the snake is kissed thrice and then the fairy would temporarily appear in her real body. In order to rid her of her snake body permanently, the prince would have to remain faithful to her for ten years. Alberic the Blond frees her by kissing the snake but fails to stay faithful for the period of ten years. Prince Alberic tries to do what his ancestor failed at but falls short against his scheming grandfather, the Duke. The Snake Lady is brutally murdered. Her death takes place in a cell where she is confined.

The Yellow Book

The Yellow Book because of its diverse content that included all sides was symptomatic rather than representative of the charged social and cultural Late-Victorian society. It participated through literature and art in the ongoing debates that defined the fin-de-siècle culture, the evolving and the reactionary politics of the avant-garde, the rejection of the old and sometimes the protest against the new (Ledger 9). The Yellow Book ran from 1894 to 1897 as a quarterly literary periodical in Britain and was published by The Bodley Head in London. The twelve quarterly issues incited sensational reactions due to their experimental and avant-garde nature and its association with Oscar Wilde’s arrest and trials (Kooistra). Vernon Lee was one of the many women writers who found space in the pages of The Yellow Book to write stories about women. Notably, in Volume 10, alongside Lee, more than half of the contributors were new, and the majority of the contributors were women, reflecting the commitment the magazine had for diversity and forward- thinking (Kooistra). Alongside Lee’s fairy tale in the volume, other ghost stories and spectral art also appear, such as “Two Stories” by Ella D’Arcy about hauntings in the home and spectral encounters as well as “La Goya” by Samuel Mathewson Scott which delves into spirituality and witchcraft. Some of the poetry in the volume maintains the same gothic elements, notably Marriott-Watson’s “D’Outre tomb” and Gore Booth’s “Finger Posts.”

In Conclusion

The 1890s literature was revolutionary in its production of works that symbolized the challenges of the British society as it exchanged the old for the new, responded to the new awareness that came with material progress and the inadequacy of religion to provide answers, and redefined old categories and created new ones. Owing to magazines like The Yellow Book there was finally space for as yet marginalized, unpopular opinions that were gaining momentum due to a class and mental shift. The fin-de-siècle with its radical discourses on science and art created new ways of thinking and allowed for old biases to be exposed. The aestheticism and decadence movements of the 1890s served similar purposes. Literature and art recorded in magazines such as The Yellow Book provide a glimpse into that world which was exploding in reaction to changes and opposing forces were battling for the preservation of old ideas as well as acceptance for new ways of thinking. Vernon Lee’s fairy tale in The Yellow Book occupies the contested space for female liberation and explores the secret desires and the inner struggles of Victorian women as they lived with little to no agency under the Victorian patriarchy.

Works Cited

- Cohen, Philip. John Evelyn Barlas, A Critical Biography: Poetry, Anarchism, and Mental Illness in Late-Victorian Britain. Rivendale Press, 2012

- Dickerson, D. Vanessa. Victorian Ghosts in the Noontide: Women Writers and the Supernatural. University of Missouri Press, 1996.

- Denisoff, Dennis and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. ” The Yellow Book: Introduction to Volume 10 (July 1896).” The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. Accessed 10 November 2018, http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV10_Intro.html

- Kandola, Sondeep. “Vernon Lee: New Woman?” Women’s Writing, vol 12, no. 3, 2005, pp. 471-84. Web. Accessed 10 November 2018. DOI: 10.1080/09699080500200264.

- Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “The Yellow Book (1894-1897): An Overview.” The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2012. Web. Accessed 10 November 2018, http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB_Overview.html

- Liggins, Emma. “Gendering the spectral encounter at the fin de siecle: unspeakability in Vernon Lee’s supernatural stories.” Gothic Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 2013, p.37+. Academic OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/apps/doc/A367421122/AONE?u=rpu_main&sid=AONE&xid=533d1987. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

- Sumpter, Caroline. The Victorian Press and the Fairy Tale. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012

- Smith, Alison. “THE ‘SNAKE BODY’ IN VICTORIAN ART.” Early Popular Visual Culture vol 3, no. 2, 2005, pp. 151-64. Web. Accessed 08 Nov. 2018. https://doi.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/10.1080/17460650500198014

- Xiao, Bin. “Morality in Victorian Period.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 5, no. 9, 2015, pp. 1815-182. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1718903348?accountid=13631, doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/10.17507/tpls.0509.07.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.