Charles Ricketts, The Dial and Sympathy Through Symbolism

© Katica Majic, Ryerson University 2018

Introduction:

The late nineteenth century was a time of subversion and change through the medium of literature in order to combat the stiff and unwavering values of England in the Victorian Era. Literature, specifically a particular form of literature—that being fantasy, folkloric, and fairy tales—had been used in a clever way of using something they valued against them by turning both the story genre and subject matter on its metaphorical head. The yellow magazine, The Dial, was a project created for this purpose. In the very first volume, it states that The Dial’s purpose is to convince and gain sympathy, but of what and for whom? While there were often different writers and artists contributing to The Dial, the content was primarily contributed by Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts, the publishers and creators of The Dial. Though, in specific, there are four stories from the second volume that I am going to be curating: The Marred Face, The Bridal, Ella the She-Bear, and The Snow in Spring, all written by Charles Ricketts. Now at face-value these stories may seem strange but given the context of the time period, the author’s own past, and a particular tendency of humanity there is likely more to these stories than what exactly is written on the pages, in fact I would argue that these pieces were used as literary rebellion against a prejudice that was close to Ricketts’s heart.

The Historical Human Condition and the Victorian Era:

The nineteenth century is well-known for many things such as its stiff nature and unforgiving views of straying from what was considered the ‘norm’ of that period. This is routed in a few human habits, the first being the tendency to go back the good old days in search of roots and identity. To the Victorian Era, the good old days were those of the Renaissance and Middle Ages (Clausen, 220-235). Figures like William Shakespeare were obsessed over to the very finest detail, most notably: the identity of a dedication for a publication of his sonnets and works like John Milton’s Paradise Lost which was previously viewed as a blasphemous work became haled as the, arguably, best epic poem from one of the first British poets (After Work, 124). Another comes from the higher class’s fear of the lower class and their allegedly ‘illicit’ activities, such as heavy drinking and sexual deviance (Tuttleton, 388-394). With this value of upper-class and abhorrence of the lower class lifestyle will lead to upper-class activities, such as appreciation of the classical literature of the Renaissance period. In any case, the Renaissance period was one that was idealized by Victorians, who took much inspiration from that period into their own culture and literature. In this way, the Renaissance was the route of Victorian aestheticism, from its appearance in the worshipped sonnets of Shakespeare to any given work of art, idealized beauty was ever present in the Renaissance and therefore reflected in the Victorian era. Another thing that was adopted from the Renaissance was its own obsession with Greek and Roman culture, specifically it’s mythology, even more specifically, portrayals of mythical and fantastical beings interacting with humans, this bore us the Victorian fairy tale (Clausen, 220-235). And just as inevitably as the search for identity is, so comes the rebellion against the identity after a period of time. The people get sick of the same thing and move on. Such is true to the Renaissance as the moved onto favour science and alchemy in the period of enlightenment, and such is true with the early to mid-1800s and the decadent late 1800s period, as there came a decay in what was valued in morals as well as what was valued in art form (Goldfarb, 369-373). . Literature especially got this treatment as the classic fairy tale stories became subverted and satirized. Literature became an artistic tool to rebel against the strict 1800s.

Charles Ricketts:

Enter Charles Ricketts: book designer, wood-carver, theatre designer, writer, and publisher among many other things related to the fine arts. Born to a French woman and English man, and an alumni to the City and Guilds Technical Art School, Ricketts became a well-respected and accomplished all-around artist. He lived with his partner Charles Shannon who was likely more than just a ‘close friend’ and in fact his lover as they lived alone together and never married or courted any women in their time. These two started to work a large project together and with some artists in their circle contributing to it, they created the Dial (Frankel, 1-3).

The Dial:

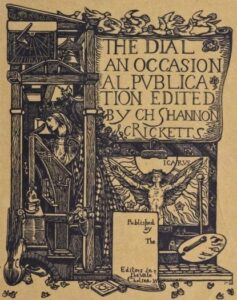

The Dial was a little magazine with an irregular release schedule created in 1889 by Charles Ricketts and his partner, Charles Shannon, who were also its primary content contributors and published by many people but most consistently by The Vale Press, another creation of Charles Ricketts. In its first volume under the section of Apology states the purpose of its publication, that being to gain the sympathy of its readers (Ricketts 1, 33), more specifically sympathy towards the close-mindedness of people and how this closed door means that they are choosing a more unorthodox point of entry into these closed minds, presumably in order to convey their message to those who will not want to hear it when given plainly (Clark, 33-50). It was also to promote the works and philosophy of a group of artists, including Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon, who often met up at the Vale, who were often referred to as the Valeists (Willford, 170-228). With this, we know that The Dials purpose is to endear a group that is disliked to the public via the unorthodox method of literature, though the remaining question is: Which group is being endeared?

Homosexuality in Victorian England:

Though they were interested in and idealized the religions and mythos of lands from afar, Victorian England was both strict and Christian, and likewise was not kind to those who fell out of line with the social norm of the time period or defied the common conception of God’s will, that will being that man shall not lay with another man in the manner that they would lay with a woman. That being said homosexuality was a crime punishable by imprisonment under the pretense of being gross indecency. Oscar Wilde, a great writer and friend to Charles Ricketts, was one famous example of someone who was tried of this offense in 1885. And when asked, ‘what is the love that dare not speak its name?’ he replies by telling the court of how the love that dare not speak its name is love as pure as any other and is unfortunately misunderstood in their day and age. How it’s present in the works of Shakespeare and Michelangelo that the public adored and yet ignored in favour of their own perception (McDiarmid, 453-454). For this, he was acquitted but later.

Homosexual in this time period was not something to be open about so individuals like Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon could not come out with this aspect of their lives so freely. Moreover, Ricketts was likely using The Dial to get readers to understand how he feels as a gay man in an unforgiving environment for homosexuality, and to see him as human without actually having to come out himself (Clark, 33-50). An incredibly popular movement came with the Renaissance revival and that movement was aestheticism, something very present in the works of Ricketts is the aesthetics of it. However, it is important to note the connotations that came with aestheticism, the idea that art and beauty need no reason to exist (Baldick, Aestheticism), and that would be effeminacy and androgyny (Willford, 33). In this way, many people who fell into the queer category, in the late 1800s, would use this aestheticism as a tool by allowing them to portray “same-sex desires as a style of artifice against nature” (Willford, iii). This made aestheticism an important aspect of the decadent movement (Goldfarb, 369-373).

Synopses:

The first story to cover is The Marred Face, coincidentally the first story in the second volume. It takes place in China as a beggar named Foo finds and makes off with the head of Chang Tei, the former lover of the Queen, which seems to gain the ability to speak when meeting the eyes of Foo. He throws the head through a window and onto the Queen’s lap. Initially, she tries to get rid of it but eventually, she enters an obsessive relationship with the head, and in being so consumed by it, is completely oblivious to the rebellion building against her until they finally break down the doors and corner her as she sings the head a song. This final scene showing just how warped her mind has become.

The second story, The Bridal, takes place, seemingly, in an ambiguously Slavic country that starts with people happily awaiting for Lord Ivan and his kinsmen to meet with his betrothed, Anna. Though, what the reader doesn’t know yet is that Lord Ivan had killed her lover, Vladimir, presumably in order to take out any competition for her hand. Anna, who is of course distressed by the fact she must now marry the murderer of her lover, is prompted to kill Ivan with his own dagger. Anna is then immediately killed by the kinsmen.

The third story, Ella the She-Bear, also takes place in an ambiguously Slavic country. It tells the tale of Ella, a she-bear that would like the ability to use spells to become beautiful and lure men, much like the greatly disliked, though powerful Elka. Ella is taken under the wing of Elka to learn how to use this magic and ends up falling for a shepherd named Stoyan, who is lured by Elka to his death. Ella comes to hate Elka for what she does, and, in grief and fear, spots someone cutting woods and throws herself under the axe to die.

The final story, The Snow in Spring, takes place in a forest where it seems a brother had committed a murder. His sister worries for his safety, for he surely will be executed for his crime but he doesn’t believe her. The forest begins to say what it will do for him when he is dead like wash the blood off his body with rain and wrap around and hold with the tree’s roots. Then suddenly it seems he must be dead already as the forest claims to be correct in its prediction and follows through with its promises. It ends with the brother being in denial of his death.

Analysis:

These stories, though bizarre in structure and subject, are likely a product of the very purpose of The Dial; to gain sympathy from its readers, but I would like to argue that these pieces are specifically trying to endear homosexual people to the reader with the use of symbolism and allegory. A common theme throughout all of these stories would be the subject of forbidden love and/or action, fantastical elements, and despite the fairy tale-like elements, always ends either bitterly or tragically, likely to show unfair it is for this group of people to be disallowed their fairy tale ending.

In The Marred Face, the relationship between the Queen and the head of Chang Tei is viewed, by the public, as abhorrent and disgusting, much like how a homosexual relationship is view by the public of Victorian England. There are elements of fairy tales like the presence of royalty and the supernatural.

The remaining three stories are grouped together, like a miniature collection of short folkloric stories. The first, The Bridal, allegorically represents the raw emotion one might feel not being able to marry the one you love and instead being forced to be with someone you cannot. Ella the She-Bear conveys an envy for the opposite sex who seems to have the ability to get anyone they want and the pain one feels when the one you love fall for somebody else. Finally, The Snow in Spring feels symbolic of the fear of the repercussions one might feel upon their sexual orientation being discovered and the denial one might feel that this might catch up to you.

Conclusion:

The reason Charles Ricketts wrote The Marred Face, The Bridal, Ella the She-Bear, and The Snow in Spring to symbolically represent how he feels as a homosexual man, without having to come out himself, to gain sympathy for his and many others’ predicament. With what happens to people who are found to be homosexual, it really isn’t surprising he opted to symbolism in order to convey these feelings as it could very well have landed himself and Shannon in jail, England, in this period, was not ready for such a progressive stance, so he had to settle for the knowledge that at the very least people lent their sympathy to homosexual oppression, even if they didn’t know it. Today, it is much more acceptable to love someone of the same sex because you will face far less discrimination than those from the generations before us, though we should never forget those who helped that social acceptability rise, for even the passive approaches, like that of Charles Ricketts, are the building blocks for progression.

Work Cited

Primary Sources

Ricketts, Charles. “Apology.” The Dial: An Occasional Publication, vol. 1, 1889, pp. 36. The Internet Archive, Getty Research Institute, https://archive.org/details/gri_33125014428227/page/n5

Ricketts, Charles. “The Marred Face.” The Dial: An Occasional Publication, vol. 2, 1892, pp. 1-7. The Internet Archive, Getty Research Institute, https://archive.org/details/gri_33125014428227/page/n5

Ricketts, Charles. “The Bridal.” The Dial: An Occasional Publication, vol. 2, 1892, pp. 29-30. The Internet Archive, Getty Research Institute, https://archive.org/details/gri_33125014428227/page/n5

Ricketts, Charles. “Ella the She-Bear.” The Dial: An Occasional Publication, vol. 2, 1892, pp. 30-32. The Internet Archive, Getty Research Institute, https://archive.org/details/gri_33125014428227/page/n5

Ricketts, Charles. “The Snow in Spring.” The Dial: An Occasional Publication, vol. 2, 1892, pp. 32-33. The Internet Archive, Getty Research Institute, https://archive.org/details/gri_33125014428227/page/n5

“Paradise Lost.”. (1885). After Work, (7), pp. 124. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/2909229?accountid=13631

Secondary Sources

Baldick, Chris. “Aestheticism.” The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. : Oxford University Press, January 01, 2008. Oxford Reference. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199208272.001.0001/acref-9780199208272-e-17.

Brooks, Michael. “Oscar Wilde, Charles Ricketts, and the Art of the Book”. Criticism: a Quarterly for Literature and the Arts, vol. 12, 1970, pp. 301-315. Periodicals Archive Online. Wayne State University Press, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1311735437?accountid=13631.

Clark, Petra. “Bitextuality, Sexuality, and the Male Aesthete in The Dial: ‘Not through an Orthodox Channel’.” English Literature in Transition, vol. 56, No. 1, 2013, pp. 33-50. MLA International Bibliography. ELT Press, http://muse.jhu.edu.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/article/493237/pdf.

Clausen, Christopher. “Victorian Literature: Can These Bones Live?” The Sewanee Review, vol. 96, no. 2, 1988, pp. 220–235. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27545880.

Frankel, Nicholas. “Charles De Sousy Ricketts (1866-1931).” The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Dennis Denisoff, Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson Digital Humanities Centre, 2010, http://1890s.ca/PDFs/ricketts_bio.pdf.

Goldfarb, Russell M. “Late Victorian Decadence.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 20, No. 4, 1962, pp. 369-373. JSTOR Information Database. The American Society for Aesthetics. https://www.jstor.org/stable/427899.

McDiarmid, Lucy. “Oscar Wilde’s Speech from the Dock.” Textual Practice, vol. 15, No. 3, 2001, pp. 453-454. Scholars Portal Journal. Villanova University, https://journals-scholarsportal-info.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/pdf/0950236x/v15i0003/447_owsftd.xml.

Tuttleton, James W. “Rehabilitating Victorian Values.” The Hudson Review, vol. 48, no. 3, 1995, pp. 388–396. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3851839.

Willford, Daniel Patrick. The Aesthetic Book of Decadent Literatures. University of California, 2015, pp. iii, 170-228. ProQuest Dissertation, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1725907177?accountid=13631.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.