Japanese Influence in The Works of The Dial

© Leila Geve Kazeminejad, Ryerson University 2018

Japanese Influence in the Works of The Dial

INTRODUCTION TO THE AUTHORS

Charles Ricketts

Charles Ricketts was known for his work in book design, illustration, publishing, and printing. Along with his lover, Charles Shannon, they edited and published The Dial and even contributed their own pieces to the magazine. He is heavily associated with Oscar Wilde as he had illustrated for Wilde’s A House of Pomegranates and The Sphinx. Ricketts was famous during his time and was highly sought after for his artistic vision and his literary prowess (Frankel pars. 1-5). In The Dial, Ricketts had wrote works like “The Cup of Happiness” which was published in volume one in 1889.

John Gray

Writer and poet, John Gray is notorious for his work, Silverpoints. He is also credited with bringing French contemporary poetry to the views of the English. A part of Oscar Wilde’s social circle with Charles Ricketts and Michael Field, Gray has been theorized to be the inspiration for Wilde’s famous book, The Picture of Dorian Gray. He is heavily associated with aestheticism and decadence due to his reputation as Dorian and the fame he acquired from Silverpoints (Literature Resource Centre secs. 1-9). In The Dial, Gray wrote pieces like “The Great Worm” which was published in the first volume during 1889.

Michael Field

A female duo comprised of Edith Cooper and Katherine Bradley, they were a homosexual coupling residing in Richmond, London. Their works were notable for its use of Greek and Elizabethan eras as well as its contributions to the literary conversations regarding aestheticism and gender during the fin-de-siècle. In the general public, Field was not critically acclaimed however, they were well known in specialized fields regarding the aesthetic and decadent genre. Their circle of connections included Oscar Wilde, Charles Ricketts, and John Gray (Evangelista, “Michael Field” pars. 1-8). In The Dial, Field wrote many pieces including “The Fate of the Crossways” which was featured in volume five, the last installation to this series of little magazines which was published in 1897.

KEY IDEA

Cultural Globalization

Cultural globalization is when one country absorbs ideas, values, and cultural practices from a foreign country. What hinders the process of cultural globalization is national pride at discriminant extremes, making those who hold this trait to be unable to see information from other countries as valuable, intelligent, or better than their own.

FOCUS

Whether your verdict on the predicament of the planet’s rapid globalization is a negative one, society as an inclusive cultural unit is difficult to imagine. Yet, in only 1854 was Europe formally introduced Japan, a nation that once got so lost in creating art “that they really didn’t give a shit about running the country” (“History of Japan” 00:01:49-153). Artists in Europe had been circulating the thought that art should be separated from politics, science, and other subjects and had coined the term “art for art’s sake” (Evangelista, “Aestheticism” 7). This movement, now known as the Aestheticism movement, strove to create art of a higher pedigree and used themes of decadence, feminism, eroticism, and homosexuality to convey the experimental nature of the movement (Evangelista, “Aestheticism” 7). While the Aestheticism movement was regarded as pretentious to the general public it was common to find unorthodox collaborations by artists and authors like The Dial by Charles Ricketts and Charles Shannon. It is under the scrutiny of the works “The Fate of the Crossways”, “The Great Worm”, and “The Cup of Happiness” that it is in my interest to explore the possibility and the plausibility of these Victorian authors being charged with a fascination of the sunrise land, Japan. At the time, Britain’s only knowledge of Japan came from the Dutch trade in Dejima or gossip dating back to even the 1500s (Law 25). Through the use of Japanese techniques and literary forms, these British authors under the guise of elevating art contributed to the common practice of cultural globalization that appears today.

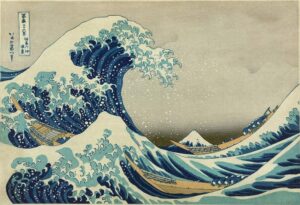

UKIYO-E AND CHARLES RICKETTS

Ukiyo-e, which translates to “pictures of the floating world” (Delay 104), originated in Japan around 1615 during the Edo period. Beginning as an exclusively black and white practice of using woodblocks to print images, it developed to become a colourful art style used by the famous Katsushika Hokusai, known most notoriously for his Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Delay 104). If you didn’t know about ukiyo-e, then it wouldn’t be apparent that Charles Ricketts frequently made use of this Japanese style of printing frequently in The Dial. Unlike the illuminated manuscripts created around 400-600 CE which were made by hand, Ricketts’ use of woodblocks to create the grandiose first letters in The Dial‘s stories rendered it unnecessary to individually paint those letters every time. Perhaps Ricketts was attracted to the quickness of what was essentially one of the earliest forms of printmaking. However, there is no reason why The Dial had to include woodblock lettering. Here, we can see a demonstration of creating art for art’s sake. The lettering does not aid in understanding the stories written in The Dial or understanding the magazine. They simply exist because Ricketts wanted to create them. Ukiyo-e is playing a part in the physical composition of these magazines, not just within their stories. Incorporating the woodblock elevated both the practice of printmaking in Victorian England and the incorporation of art in writing, ultimately making globalization a closer reality. It is said that the arrival of the superior Japanese arts threatened the British artists and writers that felt it was their duty to push art to a transnational level. By seeing Japanese art as an opportunity to extend their own limits allowed the British begin pursing art at a global scale.

THE ESCAPE FROM ANTIQUITY, THE DRAGON, AND THE KABUKI THEATRE

The English fascination with Japan not only comes from their geographical distance far east, but also from their status as an Asian country that has never been colonized by a European power (Lavery, “Japonisme” 827). This deems their land and their values purely of Asian origins. The art imported from Japan was new, unseen, and completely exotic to British eyes. While people like Michael Field and Charles Ricketts had once been tempted to completely reviving the glory of Greek antiquity (Evangelista, “Aestheticism” 14), the arrival of Japanese influence in Britain tempted them to enhance their art styles instead of recreate the techniques from an old one.

In “The Cup of Happiness”, the narrator is faced with a fork in the road. Along the road is a wall in which Hecate, goddess of ghosts and necromancy, sits silently surrounded by spirits of the dead. As the narrator chooses their path, dogs bark and howl in their wake. This story seems to lack any traits of Japanese influence in favour of Greek mythology. However, the narrator seems to be escaping Hecate, the spirits, and her dogs which lead me to think that Field is conveying an escape from classical antiquity. This is taken from the observation that Hecate and the spirits seem to have hold on the narrator, as if all the dead artists and authors of classical antiquity are waiting to be brought back to life with the narrator’s decision. Field wrote that “With a fear that was nearly blind, and intensity that was actual anguish, I made my choice…” (Field 11), which comes off as if they have thrown away or abandoned something that was once important by choosing this path. By using the figure of Hecate, Field turns away from her and runs towards a new goal. The unfamiliarity of the art from the far east suggests that the new path Field now traverses is towards being inspired by Japanese art rather than those from classical antiquity.

In contrast, “The Great Worm” is a story that seems to comment on Mortimer Menpes and his teachings from Japan. The narrative follows a dragon that journeys to the palace of a prince. He becomes a general and begins his mission of reconquering the neighbouring tribes. His expedition is a peaceful one, but as the dragon and his forces travel towards a green city in the desert, a lady of white with corn coloured hair gives him a lily and rides off in her chariot. Soon after, the dragon dies and is reincarnated next to a poet. Generally Japanese dragons have a serpentine build and benevolent personality, which leads me to believe that Gray sees the dragon as an embodiment of Japanese art.

In the story, the dragon is a fascination to all that he meets. It is only when he reaches a truly foreign land that he succumbs to death. When the dragon is reincarnated, he is not what he once was but a faintly similar being. These observations hint that this is about Menpes who came back to Britain only to be criticized by Oscar Wilde (Lavery, Remote Proximities, 1161). Wilde stated that

‘He did not know that the Japanese people are, as I have said, simply a mode of style, an exquisite fancy of art’ (Lavery, Remote Proximities, 1161)

which suggests that Wilde believed that Menpes’ travels were pointless. What Menpes came back to display in Britain was not the beloved form of Japanese art made by the masters, it was a westernized version of Japanese scenery. Therefore, like the how the dragon died and came back a different version of himself, Menpes’ paintings from Japan are a step to killing the authentic art. What he should have done was not to replicate Japanese art, but advance his own art using elements learned from it. Gray’s commentary upon this interaction between Wilde and Menpes displays a boundary between experimenting and copying and that British art can become elevated through getting inspiration from Japanese art.

Ricketts uses aspects of Japanese culture in his story “The Cup of Happiness” such as the Shinto religion and Kabuki theatre. Essentially the story is a play within a play and the characters in the play are aware that it is a play. The characters include the Prince, a Monster, Fantasy, and personifications of nature. A clown warns that the Cup of Happiness is fake and the Prince leaves his opulent palace to seek out the Cup of Happiness. In his travels, he meets a Palm Tree, Thunder, Lightning, the Monster, and Fantasy. Plays in Japan, called Kabuki were plays “derived from epics and legends” (Delay 108) that were played by an all male cast.

In the story, it states that “the play is old, old as Comedy herself” (Ricketts 27), which suggests that the play in the “The Cup of Happiness” is based on something like an epic or legend. It has been said that

This new theatrical genre, with its stage, spectators, boxes and legendary heroes, was an endless source of inspiration for the ukiyo-e artists (Delay 108)

which seems fitting because Ricketts also utilized ukiyo-e. However, that is not the only element of Japanese culture that has been absorbed by Ricketts in this story. He also personifies nature, like Palm Tree and Thunder which is like the Shinto belief that everything in the world has a spirit (Delay 20). But the most notable feature of Shinto religion is when two female figures in the story perform acts similar to the the tale of the goddess of the sun, Amaterasu going into hiding. After Amaterasu hides, the goddess of laughter, Ama no Uzume began to dance in front of the entrance Amaterasu was hiding behind. She strips naked and loses herself to the dance. This scene is like when the muse “danced with mad rapture” (Ricketts 28) and in the end when Fantasy “escapes from her clothes, and with her hair streaming behind her like a comet dances about the stage naked” (Ricketts 33). Ricketts taking these Japanese ideas and incorporating them into British art is not an act of copying, it is the beginnings of cultural globalization. In his aesthete mission to experiment with art, the Japanese culture had been absorbed into British society.

CONCLUSION

As much as we value national pride , it is when we humble ourselves to seek out and accept the viewpoints of others that countries grow in all aspects. As Britain was culturally becoming more eclectic, the Japanese had been changing their government, education, and language since obtaining information through the Dutch trade at Dejima. The Dial, published during the late 1800s was well received among the public, but was predicted to be unable to hold longevity (Claes pars. 1-2). Maybe this was because as the audience learned more about Japan, the more they would try to seek out authentic Japanese arts like The Tale of Genji and Katsushika Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji instead of the Japanese inspired magazines and artworks by the British. However, as artists became selective of the elements they put in their art, it opened a door for the world to accept other aspects of foreign cultures which is where we get cultural globalization.

WORKS CITED

Brooks, Michael. “Oscar Wilde, Charles Ricketts, and the Art of the Book.” Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts, vol.12 iss. 4, Wayne State University Press, 1970, pp. 301-319. Proquest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1311735437?accountid=13631.

Claes, Koenraad. “Dial (1889-1897)”, C19 The Nineteenth Century Index. Watry 2004.

Evangelista, Stefano. “Aestheticism.” The Encyclopedia of Victorian Literature, edited by Felluga, Dino Franco, et al, vol. I A-D, Wiley Blackwell, 2015, pp. 7-16.

Evangelista, Stefano. “Michael Field (Katharine Bradley, 1846-1914; and Edith Cooper, 1862-1913)” The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Denisoff, Dennis and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University, 2015. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=field_bio.html

Field, Michael. “The Fate of the Crossways.” The Dial, edited by Ricketts, Charles and Charles Shannon, vol. 5, The Vale Press, 1897, pp. 11. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/stream/gri_33125014428300#page/n27/mode/2up/search/Field.

Gray, John. “The Great Worm.” The Dial, edited by Ricketts, Charles and Charles Shannon, vol. 1, The Vale Press, 1889, pp. 14-18. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/stream/gri_33125014428284#page/n23/mode/2up/search/worm.

“History of Japan.” Youtube, uploaded by Bill Wurtz, 2 Feb. 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mh5LY4Mz15o&t=115s

“John (Henry) Gray.” Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2003. Literature Resource Centre, http://link.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/apps/doc/H1000039005/LitRC?u=rpu_main&sidLtRC&xid=c463606f.

Lavery, Joseph. “Japonisme.” The Encyclopedia of Victorian Literature, edited by Felluga, Dino Franco, et al, vol. II E-L, Wiley Blackwell, 2015, pp. 827-829.

Lavery, Joseph. “Remote Proximities: Aesthetics, Orientalism, and the Intimate Life of Japanese Objects.” ELH, vol. 83 no.4, John Hopkins University Press, 2016, pp.1159-1183. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/elh.2016.0043.

Law, Graham. “Japan.” The Encyclopedia of Victorian Literature, edited by Felluga, Dino Franco, et al, vol. II E-L, Wiley Blackwell, 2015, pp. 825-827.

Nicolas Frankel. “Charles de Sousy Ricketts (1836-1931).” The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Denisoff, Dennis and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University, 2010. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=ricketts_bio.html

Ricketts, Charles. “The Cup of Happiness.” The Dial, edited by Ricketts, Charles and Charles Shannon, vol. 1, The Vale Press, 1889, pp. 27-33. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/stream/gri_33125014428284#page/n43/mode/2up/search/Happiness

West, Shearer. “The Visual Arts.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siècle, edited by Marshall, Gail, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 131-152.