Radical Femininity and New Woman Fiction in Michael Field’s “Equal Love”

© Tanis Smither, Ryerson University 2018

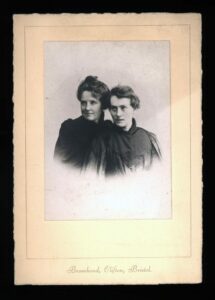

In this digital exhibition, I have chosen to curate Michael Field’s “Equal Love,” published in Volume 1 of The Pageant (December 1896) because I want to find out how Michael Field’s use of a New Woman character was informed by their own lifestyle, to better understand Victorian femininity. Michael Field was the joint pseudonym of Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper. Bradley, born in Birmingham on October 27th, 1846, was the aunt of Edith Cooper, who was born on January 12th, 1862 in Warwickshire. Bradley went to live at the Cooper household after Edith’s mother became ill, and the two women formed a fierce bond. They developed a romantic attachment and lived together for the rest of their lives. “Equal Love” is their blank verse drama, and although it is situated in a fantasy and folklore heavy issue of The Pageant, it stands out starkly as one of the only female-produced entries in the larger work. For the purposes of this exhibit, a working definition of folklore is necessary. The Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore defines folklore as:

A record manner of customs that are retold through different forms of media over several generations, often in different languages. This is done as a way of passing on information and traditions from the past to dynamically educate those in the present. A survival of the past that is constantly developing to educate future societies” (Simpson & Roud, 2003).

This is by no means a summative definition of all folklore, however it is pertinent to represent how the editors of The Pageant may have characterised the genre for this specific work.

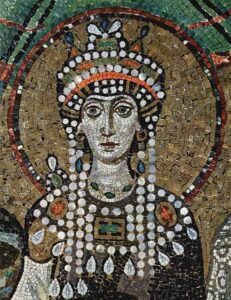

“Equal Love” is based on a real Emperor and Empress of Byzantine, although Theodora (the Empress) is the protagonist of choice for Michael Field. In the context of my research, it is important to note here that I believe “Equal Love” is an ironic title. It is my contention that the title suggests that although Theodora may be powerful, she is still unequal to her husband. In “Equal Love,” Bradley and Cooper emphasise Theodora of Byzantium’s real-life qualities in order to position her as a Roman New Woman, bringing their Victorian modernity to a historical drama and use fin-de-siècle notions of radical femininity and the taboo. This digital exhibit will use “Equal Love” in conjunction with the unorthodox nature of the relationship between Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper as a lens through which to explore fin-de-siècle femininity and position Michael Field as Victorian New Women.

Michael Field is a (New) Woman

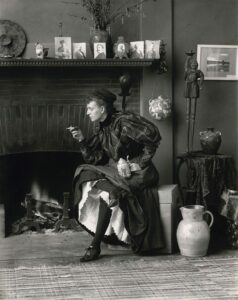

Although Bradley and Cooper (right) were not necessarily the New Women of the Victorian photographs—they reportedly eschewed cross-dressing and champions of the Rational Dress movement (Pionke 27)—it can be argued that the two women who penned under the Michael Field name were in their own way champions of the New Woman movement. In her essay “Michael Field: Gender Knot,” Katharine (JJ) Pionke argues that Bradley and Cooper took more to the New Woman lifestyle in their writing than their personal life (27). While it is relatively undisputed that their writing is radical for the Victorian era, I argue that the very decision to use their male pseudonyms in their day-to-day lives with friends and each other states undeniably that the two women were attempting to “challenge the male literary privilege” (Pionke 27), which is a hallmark of New Woman fiction.

Theodora: The Roman New Woman

“Equal Love” is remarkable in its historical context. Despite the fact that the rise and fall of the Roman Empire is dominated by stories of men and their rule, the focal point of interest to Bradley and Cooper is the woman behind the great Emperor of Byzantium. Theodora was a real Byzantine Empress (Britannica 2018). Bradley and Cooper do dramatise her relationship with her illegitimate son Zuhair, however most other aspects of Theodora’s character are based in fact. She was initially a prostitute, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. She was also rescued from destitution by her husband Justinian, who had to change the laws of Byzantium in order to marry her. It is known that she co-authored and pushed forward many laws for the Empire, as her name is on almost all of them from the time of her Empressdom to that of her death. Finally and perhaps most importantly, Theodora is “remembered as one of the first rulers to recognize the rights of women” (Britannica 2018). Her political prowess at a time when women were expected to be wives and mothers firmly situated Theodora as a Roman New Woman.

In her book The New Woman and The Victorian Novel, Gail Cunningham characterises Victorian New Woman fiction as having a basic pattern in which the protagonist suddenly and inexplicably marries the wrong man, making an initially successful bid for freedom and then collapses into “crushing conformity” (106). Although it is clear Theodora’s character does not fit entirely into this category, it is obvious that Bradley and Cooper followed this formula at least loosely in the trajectory of Theodora’s story. They highlight her political power and her feminist approach toward lawmaking in one fell swoop: she asks her husband to leave the room to work on the laws they discussed together, and it is more command than gentle request. The proposed law requires marriage regulations contain more freedom for women (Field 204). Like Bradley and Cooper themselves, Theodora can be read at surface level as a Roman New Woman, but she is still bound by certain unavoidable gender conventions of the time period. For example, when Justinian threatens divorce if she does not get rid of her illegitimate son, Theodora begs him to reconsider, saying: “Divorced? That shall not be/That were an annihilation…If you dis-espouse me,/have you thought how I must perish?” (Field 215). For Bradley and Cooper history is “a screen upon which to discuss the contemporaneous” (Parejo 237), and if they felt at all stifled by Victorian notions of marriage and femininity, it is clear they used their writings in “Equal Love” and the character of Theodora as a vehicle to comment on and discuss those feelings.

Lesbianism, Incest and Infanticide (Oh my!)

There has been ample debate in the scholarly community surrounding Michael Field and their relationship. Many scholars have argued that the two women, although deeply attached to one another, were not romantically entwined. These arguments suggest scholars collectively fetishise Victorian female friendship by stating the two were at all involved in incestuous behaviour. However, it is my contention that in an ironically stiff-collared, Victorian-like necessity to stifle the taboo of Bradley and Cooper’s relationship, the scholars who argue they were simply close friends do a disservice the radical nature of their relationship and therefore the success of their works, which are undeniably tied to their personal relationship. According to Carolyn Tate and her essay “Lesbian Incest as Queer Kinship: Michael Field and the Erotic Middle-Class Victorian Family,” sexual relationships between family members were not as uncommon in Victorian society as one may like to think (181). Indeed, much of Victorian and Edwardian literature about the middle and upper classes involve at least one marital match between first cousins. It is, however, the combination of Michael Field’s status as aunt and niece, their romantic connection and their relatively conspicuous presence in the literary scene that makes their relationship radical. The two were infamously outed as women unintentionally after the roaring success of their first published work under the name Michael Field by their friend Robert Browning (Pionke 27). Instead of choosing to change their pseudonym and continue under a different male guise, the two women remained “Michael Field.” This, according to Pionke, suggests that Bradley and Cooper “wanted to experience life not necessarily as a man would, but rather as strong women” (27). This is an obviously radical decision for the time, given Bradley and Cooper’s overtly erotic poetry in conjunction with the Victorians public attitude toward same-sex and incestuous relationships, and further cements Bradley and Cooper as themselves New Women.

In “Equal Love,” the most radical action Michael Field’s protagonist takes is to murder her son. At the beginning of the play, there are a few references to a curse placed on Theodora that she may never bear a living child. Theodora believes this curse to be true after her daughter with Justinian dies in infancy, and foreshadows a self-fulfilling prophecy which hinges upon Theodora’s decision to save her Empire and her place in the political spectrum. There are many instances of Theodora’s radicality throughout the play. She is politically powerful; she is intelligent and beautiful enough to have a statesmen raise her up from the depths of poverty and prostitution to the throne; Justinian does not even seem phased by the idea that she has an illegitimate child, until he thinks his position as Emperor might be threatened. Most radical of all, the matriarchal character takes away her own matriarchy (Field 1896). The stability of the empire rests on the notion that Theodora birth a living male heir to succeed her husband. Unfortunately, when Zuhair enters the picture a bastard, Theodora is confronted with a choice: her husband will divorce her if she neglects to get rid of the potential usurper. Clearly, she sees Zuhair and his illegitimacy as a more unfortunate fate for the Empire than potentially having no biological successor at all. So the taboo writers create a taboo story, in a time when women were expected to marry men, have children by them and stick to their wifely duties.

Figure 4, Selwyn Image, Front cover design, The Pageant, vol. 1, December 1896, The Yellow Nineties Online. Public Domain.

In Conclusion

There are many possible interpretations of the Field’s chosen title “Equal Love.” The allegorical approach to the title is to note Theodora’s sacrifice—the love of her Empire winning out over the love of her child, and perhaps in the process this positions Theodora as power-hungry. I posit that this reading is too simple. By “Equal Love,” Bradley and Cooper meant to comment on the trappings of femininity in Victorian society by highlighting the trappings of Theodora’s Byzantine femininity. This illustrates that women in Victorian society may have more options or power than a woman of Byzantium, but they are still in no way equal to their male counterparts. It is arguable that Michael Field’s Theodora knew Justinian would be a less effective ruler were she not informing the majority of his lawmaking and warfare decisions. As such, her decision to kill Zuhair and remain Empress of Byzantium was made for the greater good rather than personal happiness. This idea that a woman can reject her maternal instinct in favour of her political position is a radical one, no doubt. It is also, however, a telling choice to have Justinian utter the final speech of the play: “ours is an equal love” (Field, 1896). This is where the irony lies. The New Woman of both the Roman Empire and Victorian England, it seems, is incapable of transcending gender enough to have everything. Theodora cannot have her empire and her illegitimate son, and Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper could not have their Victorian literary success while conforming to the expectations of Victorian middle-class women.

Works Cited

Cunningham, Gail. The New Woman and the Victorian Novel. The MacMillan Press Ltd, 1978.

Field, Michael. “Equal Love”. The Pageant, Vol. 1, 1896. Yellow Nineties Online. Centre for Digital Humanities: Ryerson University, 2018, https://archive.org/stream/Pageant1896_201609/Pageant1896#page/n7/mode/2up/search/Equal.

Pionke, Katharine (JJ). “Michael Field: Gender Knot.” Michael Field and Their World, The Rivendale Press, 2007.

Roud, Stephen and Jaqueline Simpson. “Folk Lore (the word)”. A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford University Press, 2003. Internet Archive, http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/view/10.1093/acref/9780198607663.001.0001/acref-9780198607663-e-375?rskey=sC2LIw&result=375

Tate, Carolyn. “Lesbian Incest as Queer Kinship: Michael Field and the Erotic Middle-Class Victorian Family.” Victorian Review, vol. 39, no. 2, 2013, pp. 181–199. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24497077.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Theodora.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. October 19, 2018 https://www.britannica.com/biography/Theodora-Byzantine-empress-died-548

Vadillo, Ana Parejo. “Outmoded Dramas: History and Modernity in Michael Field’s Aesthetic Plays.” Michael Field and Their World, The Rivendale Press, 2007.