The Full Context of the “Flying Fish,” by John Gray

©Joshua Reynolds, Ryerson University, 2018

Introduction

The “Flying Fish” is a poem about a pirate named Hang, who is telling a story about six unique birds, five of which he remembers, and five strange fish. A further examination of the poem requires answers to a few questions, which are, in order of mention: why was the “Flying Fish” published in the Dial? Why is the framing device a pirate mentoring his son? Why are there five fish and six birds, when only the flying fish is the poem’s focus? Why does that flying fish fail? The answers to these questions will reveal most, if not all, of the context to the “Flying Fish.

Why was the “Flying Fish” Published in the Dial?

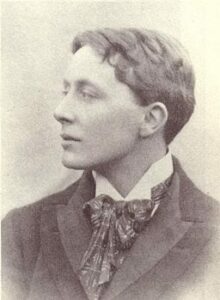

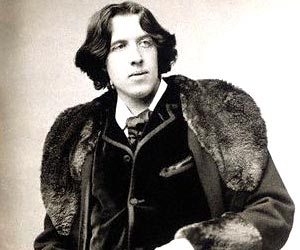

It was one of the only places that would’ve published work from John Gray, whose career was thrown into turmoil by the arrest of Oscar Wilde, which happened less than a year before the publication of the Dial’s fourth volume (Times, 1989.) One of the biggest reasons Gray became remotely notable was Oscar Wilde, who helped him with his poetry and improved his status as an author (Gale, 2003.) Incidentally, it’s believed that Gray met Wilde through Charles Ricketts, who was also a co-publisher of the Dial (2003.) Gray’s relationship with the Dial spanned much of its publication, including the “Great Worm,” which was printed in the magazine’s first volume (Gray, 1889, pp. 14-18.) It’s likely that Gray felt safe writing for the Dial, with it being a frequent platform of his and published by editors he knew.

However, publishing not just one, but three poems and an article by an associate of Oscar Wilde, in 1896, required great courage. Ricketts, who, himself, was gay, could’ve exposed himself to immense humiliation by bucking the witch hunt against Wilde’s friends. When the Yellow Book was falsely reported to have been carried by Wilde when he was arrested in 1895, a mob formed outside the publishing house of the magazine, which resulted in property damage. (Marcovitch, 2016.) This led to a full scale purge of those linked to Wilde, like Aubrey Beardsley, who was fired from the Yellow Book because he was loosely affiliated with the man (2016.) Yet, Ricketts gave John Gray a voice, in an open act of rebellion against the restrictions of 1890s British culture, and one of the times the Dial came closest to accomplishing its countercultural mission.

That said, the Dial was not a huge platform for Gray. In fact, it only had a circulation of a few hundred copies, and was targeted towards art collectors (Claes, 2005.) In between the various paintings would be some kind of text, often written by John Gray, but the show was undoubtedly stolen by the paintings and lithographs of Ricketts. Gray published the “Flying Fish” due to the backbone of Charles Ricketts, but hardly anyone noticed.

Why is the Framing Device a Pirate Mentoring His Son?

The poem starts with Hang telling his son about a voyage he had during his pirate career. Strangely, the dad doesn’t talk much about where he was going or who he was stealing from, but he talks a lot about some weird birds and fish he encountered (Gray, 1896, pp. 3.) Since the dad is obviously not teaching the child about being a pirate, he must be telling the story of the birds and fish to instill a moral. Therefore, the pirate is a way for Gray to keep us extra focused on his lesson.

There might be more to it, though. The pirate’s purpose may be to emphasize the moral, but Gray wanted it to be obvious for a reason. The poem is called the “Flying Fish,” which is about the fish that flies high and falls hard on the ship’s deck. Contrast this to Gray, who was falling into trouble, like most of Wilde’s entourage, and might have thought his career was ending, especially with the witch hunt. Perhaps Gray was depressed, trying hard to teach others who still had prominence to be mindful of their roots, so as to avoid a hard landing. The warning, of how quickly a proud fish can turn into ugly nothingness, is shown explicitly in the poem, as the fish, while dying turns into an pale and unsightly creature. (Gray, 1896, pp. 5.) Gray, who came from a working class family, may have felt that he flew too high, setting himself up for his own hard fall (Gale, 2003.) If this reading is true, he would’ve been desperate, indeed, to publish while he was still somewhat relevant.

Why are There Five Fish and Six Birds, When Only the Flying Fish is the Poem’s Focus?

The “Flying Fish” has a number of creatures, not just the one mentioned in the title. They seem to be fairly normal, doing what one would expect. There’s a dolphin, a swordfish, and a pelican, which would be some of the stronger fish and other aquatic animals in the sea. They’re accompanied by an ugly, pale bird and a fish that’s “naught but a feeble tail” (Gray, 1896, pp. 3-4.) Gray chose to describe both strong and weak creatures, but all of them stay in their own lanes, as opposed to the flying fish.

The other animals serve two purposes. The first is that they contrast with the ambitious flying fish, which causes misery for itself while they live contentedly. The second is closely related, and has to do with the average citizens of the 1890s, moving along, rich and poor. Upward mobility in the 1890s was still a relatively new invention, with the Education Act only being passed in 1870, 26 years before the ‘Flying Fish’s” publication (Auerbach, 2010.) Public schooling, a main driver of upward mobility, was quite a new concept, and one had to be lucky or exceptionally gifted to get into a worthy school. Luckily for John Gray, he found his way into one (Gale, 2003.) This allowed him to gain a leg up on the rest of the working class, who could be considered the weak and sickly-looking creatures of the poem; perhaps the forgotten bird could be the poorest of all. Gray ascended, taking advantage of a rare opportunity and rising to meet others of more powerful stock than himself. The fish were to stay the same, but Gray thought he could be better. Of course, the poem is about his realization that he wasn’t superior, after all.

Why Does that Flying Fish Fail?

There’s little doubt that John Gray, consciously or not, created a poem that perfectly reflected his career trajectory. He began his life as a working class boy and worked fairly hard but got really lucky, meeting key figures in the Decadent movement including Charles Ricketts and, of course, Oscar Wilde (Gale, 2003.) Oscar Wilde, among other things, is said to have based the title character of Dorian Gray on John, who wrote a book, which was long suppressed, that was similar to Wilde’s book ( 2003.) However, even if the belief that John Gray helped inspire Dorian is true, that does not mean Gray was an especially talented writer. He never wrote anything that was half as successful as Dorian, and is far from a household name. Even what was arguably his biggest contribution, the incidental fact that he was in close enough proximity to Wilde to inspire a major novel, is pathetic. After his fall, instead of dying on the deck of a junk, he became a priest, and significantly less prolific (2003.)

In the poem, the flying fish fails to land because Gray was failing. The main force behind his career was gone, and even the Decadent movement, itself, was on the outs after the arrest of Wilde (Denisoff, 2007.) It cannot be emphasized enough that Oscar Wilde was what picked up John Gray and elevated him; without him, Gray was subjected to the laws of gravity. He lost all control; the control of his descent included. If he was able to adapt, he might have been able to control his descent, but when the tide went out on his career, the trappings of being around the right person at the right time were exposed. John Gray truly was the flying fish who lost all control.

While he received mild critical attention after the Decadent movement, with his last collection of poetry, the generically named Poems, being called proof of his evolution from a youthful Decadent poet to a mature writer, Gray’s work was quickly forgotten (2003.) It’s true that there was a surge of interest in the 1890s after Richard Ellmann’s biography of Oscar Wilde, and many smaller writers have received academic attention, not much mainstream attention has been given to John Gray, and it is unlikely that it will ever receive any (Freeman, 2017.)

Yet, John Gray had many redeeming qualities, including an acute self-awareness that’s obvious throughout the “Flying Fish.” He seems to have realized that his career was doomed, and tried to warn others, in his own way. Granted, the overarching moral of the “Flying Fish,” that one should not be ambitious, could be considered dubious. However, I would like to propose another moral, that John Gray might have been trying to get across all along.

A Charitable Reading of the “Flying Fish”

It’s theoretically possible for the cynical reading to be perceived as too harsh, and it may be appropriate to look in a different direction, in order to see matters from another angle. The moral, from this perspective, should be seen as the need to avoid excessive ambition. It is impossible, for instance, for a fish to be a bird, because a fish is nothing without water. Meanwhile, the other four fish and six birds live in piece because they have enough self awareness and discipline to not get distracted by wild fantasies. It is the difference between pushing oneself above what is wise – or, in this case, above water – and knowing one’s limits. The moral, simply put, is to be content with what one has, which is valuable enough to teach yourself and pass the lesson on to children, like Hang does. This reading does not lend itself to much analysis of John Gray or any of his work, but it is definitely the nicest possible view of the “Flying Fish,” at least from the perspective of John Gray’s legacy.

Conclusion

John Gray’s the “Flying Fish” is best seen as an allegory of his career. The working class child grew into a confidante of one of the best known writers of his day, which is no mean feat, although it doesn’t say much about Gray’s personal ability. However, he was published in the Dial because it was a sort of refuge for him and his work. If one gives a pragmatic, slightly cynical reading, the pirate narrates the story because John Gray felt his moral was especially urgent, even though telling readers to not have dreams is dubious. Gray also seemed to want the reader to aspire to the regular animals; in short, he demanded that they aspire to have no aspirations. The flying fish, then, fails because Gray sought to project his failures onto his viewers, as if they were a kind of virtue. The other way of looking at it is that the Flying Fish is about the dangers of fantasies, although this would merely encourage complacency and a serious lack of innovation. The full context of the Flying Fish is that it is a poem by a flailing and jaded author, who is only somewhat sympathetic because he read the writing on the wall.

Special Thanks to

Oscar Wilde and Charles Ricketts, for making John Gray’s career possible.

Works Cited

“Arrest of Mr. Oscar Wilde; 06 April 1895.” Times [London, England], 6 Apr. 1989. Academic OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A117216779/AONE?u=rpu_main&sid=AONE&xid=14a166ca. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

Auerbach, Sascha. “”A Right Sort of Man”: Gender, Class Identity, and Social Reform in Late- Victorian Britain.” Journal of Policy History, vol. 22 no. 1, 2010, pp. 64-94. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/370367. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

Claes, Koenraad. “DIAL (1889–1897).” C19Index.Com, ProQuest LLC, 2005, gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&res_dat=xri:c19index-us&rft_dat=xri:c19index:DNCJ:403. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

Denisoff, Dennis. “Decadence and Aestheticism.” The Cambridge Companion to the Fin De Siècle, edited by Gail Marshall, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, pp. 31–52. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

Freeman, Nick. “‘Poisonous Honey’: Recent Writing on Decadence and the 1890s.” Literature Compass, vol. 14, no. 9, 2017, pp. 11-n/a. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

Gray, John. “‘Flying Fish.’” The Dial, 1896, pp. 1–6, archive.org/details/dial_04/page/n17.

Gray, John. “‘Great Worm.’” The Dial, 1889, pp. 14–18, https://archive.org/details/dial_01/page/n33

“John (Henry) Gray.” Contemporary Authors Online, Gale, 2003. Literature Resource Center, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/H1000039005/LitRC?u=rpu_main&sid=LitRC&xid=c463606f. Accessed 29 Nov. 2018.

Marcovitch, Heather. “The Yellow Book: Reshaping the Fin De Siècle.” Literature Compass, vol. 13, no. 2, 2016, pp. 79-87.

Disclaimer:

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education. This work is under a creative commons license and is free for use so long as it is credited, in accordance with the policies of the Y90s Classroom.