Fiona Macleod’s Role in the Celtic Revivalist Movement Through “Mary of the Gael”

©2019 Shawna Cormier, Ryerson University

Introduction

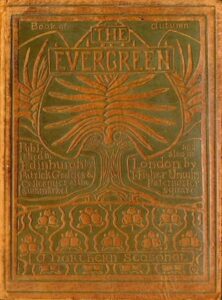

From 1895 to 1897, at the height of the little magazine’s popularity, the Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal added its own unique voice to the major issues circulating at the time, mainly speaking on the underrepresented social and political Celtic ideals, and in effect greatly contributing to the Celtic revivalist movement through its retelling of classic Celtic folktales and other stories (Grilli 20). Of the multitude of voices that added their own unique talents and perspectives to this conversation, Fiona Macleod was a major contributor, and through her retelling of the classic Irish folktale Mary of the Gael, as published in volume 2 of the Evergreen in 1895, she gave a small insight into her particular role in the cultivation of Celtic culturalism and how, through her tales, she managed to created a name for herself at the forefront of the Celtic revivalist movement.

About Fiona Macleod

Fiona Macleod was the alternate personality of William Sharp, born on September 12th, 1855 in Paisley, Scotland. Sharp was also an acclaimed author, and wrote many other poetic and biographical works, mostly centered around Scottish culture. While Sharp himself did contribute greatly to the Celtic revivalist movement, Macleod was widely known and praised for her important contributions, and was even credited for being the one and possibly only highland novelists of the time (Harris 164). She also worked closely with other famous Celtic writers through correspondence such as W.B Yeats, who praised her and her contributions to the movement, claiming he owed thanks to the “phantom Fiona,” (Garbaty 466) owing to the fact that they never got to actually meet in person. Through Macleod and Sharp’s writings, they found ways to rediscover the past and “rouse a mightier literature,” (Ferguson 162), bringing back the important influential and relevant pieces of Celtic folklore from the past to spur a new age of Celtic culturalism.

Scottish Unrest in the 1890s

In the eighteenth century, the British Union Act was put in place which dampened the Scottish culture as the British went about asserting their dominance over the Celtic lands (Ireland, Scotland and Wales), forcing Celts to assimilate to what they believed to be proper civilized ways of English living (Brekalo 46). Much of this forced assimilation stemmed from the idea that the Celtic lands were of ancient minority culture, and it became necessary for them to be absorbed into the emerging larger nation states, (this is also seen later in history such as when Poland became absorbed into Russia) (Marcus 73). This takeover and domination from the English led to a fragmented Celtic political identity, which was consequent from what was at the time an unfinished national Celtic history. While the Celts may have had a rich history in the eighteenth century, years of English repression had more or less led to an erasure of that history, leaving Scotland with little of their own personal cultural identity (Morris 90). Scotland suffered from this cultural dysphoria, but many waves of crusades happened throughout history as groups of culturalists fought to reclaim their Celtic identities. Sometimes this was done through physical violence, but in the nineteenth century, specifically in the 1890s, much of this was done through writing.

The Role of the Evergreen in the Revivalist Movement and Macleod’s Contributions

In the traditional Scottish education system, it wasn’t until 1894 when history was even introduced into the curriculum (Anderson 2), making the arrival of the Evergreen a year later well timed, as it provided a supplementary source of cultural historical folktales at an affordable price for students in addition to the real world history finally being taught in schools. Part of the reason Scottish culture was finally introduced was due to the realization that history was important to be taught as it was almost training for citizenship (Anderson 16), as after being culturally oppressed for so long under the English rule it was necessary to let students understand and learn their cultural identity. Sharp observed how through the popularizing and reviving of Celtic folklore as a framework of the human experience, it went directly counter to the traditional English ideals of “progress and enlightenment” through literary realism (Harris 190). This proved to be a welcome opening for Macleod to use her writing as an outlet of which to directly attack the British influence that had invaded the Celtic lands and reclaim their culture through traditional folklore.

Although Macleod and Sharp fought for the freedom of the Celtic culture, there was a clear divide in the movement itself between those who believed more in a “Gaelic Revival,” attempting to fight for those who were actually fluent in Gaelic and whom they perceived as a more “traditional” Celt (Marcus 79), of which Macleod herself agreed to, even though this ideology alienated English writers who were for the cause. However, this gives one clue as to why Macleod would reintroduce Mary of the Gael over all other stories, as it was a traditional Gaelic Irish tale. Due to the English attempts to force hegemony among the Celts during the Union Act, the English government prohibited the use of minority languages, discouraging Celts to practice their own national language (Anderson 17), which led to a need to preserve it even more during the nineteenth century movements.

Summary of Mary of the Gael

Using the classic folktales found among the untapped and unfinished Celtic history, Macleod resurrected important literary works that were vital in the original cultivation of the Celtic culture, some of which she also later published both outside of and in other volumes of the Evergreen, such as The Anointed Man in volume 1 or The Kingdom of Earth in volume 3. Mary of the Gael is an Gaelic Irish tale that follows the life of St. Brigid, or Bride, who was born out of wedlock. After her mother died in childbirth, she and her father were forced to flee their home in shame, and when they arrived in their new home of Iona, the ancient Druids of the land foretold of a prophecy, in which Bride would grow up to become an extremely important and revered figure. Bride grew to be a lovely and honorable, often depicted as being highly virtuous and widely respected. Eventually, the prophecy came to fruition as the virgin Mary came begging for a place to stay when she was heavy with child, and Bride gave her shelter in her manager, where Mary gave birth to Jesus. It was there that Bride nursed and sang to the child, and was adopted into the family as Jesus’ foster mother.

Symbolism/ Parallels in the story and the Movement

Macleod used this tale for many reasons, one of which probably being in how it fought against the English version of a official religion by bringing back the traditional folk religion. It is also the theme of rebirth that most likely drove Macleod to bring back this influential story, with the life of Bride and Jesus being metaphors for the revivalist movement as the Celts attempted to reclaim their heritage and be reborn against in spite of the British invasion.

The theme of rebirth is clearly prevalent through Jesus, in which rebirth here means the recovering of the Celtic culture, and in its own way depicts Bride as a symbol for those who fought for that revival. In Mary of the Gael, the story began as Bride was born in sin out of wedlock, forcing her and her father to be exiled from their kingdom of Aodh and flee in shame out of what he had done. However, before they left a famous seer from their land claimed that Bride would grow up to be an important person and do great things. At the end of the story, when Christ was born and accepted Bride as his foster mother, the prophecy came to fruition and everyone accepted Bride as a holy figure. This story parallels the state of Scotland, with Bride being the oppressed Celts who were shamed for their way of life by the English (who, in this case is the society that cast out Bride and her father) as well as those like Macleod who fought for their freedom to reclaim their culture proudly. When Bride proved herself to be worthy by her own merit despite the shameful events of her birth, she represented the true beauty and holiness to the authentic Celtic culture and how it was something to be proud of, despite what others may think or say of it.

Continuing in the theme of symbolism, there is the very important scene in which Bride is wandering and comes upon a lamb stuck in a crevice and kept under the watchful eye of a nearby falcon, which is known as a common symbol for hunting. The falcon lusts for blood and violence, but Bride intervenes and saves the lamb, holding it to her chest as if it was a newborn babe. This is foreshadowing to when she later holds the newborn Christ in her arms, except at that point they are safe in the manger. This runs parallel to the Celtic movement, as many of the earlier attempts at liberation involved some form of violence, of which Sharp was not a fan of. In his (and Macleods) attempt to fight their battle with the English, they chose the much more passive form of writing to get their message across, which mimics the safety of the second rebirth scene.

A Female Perspective-Why Macleod?

In all of this, there was one more question: why would Sharp use Macleod to retell this story instead of publishing it himself? Macleod’s other writings tended to be centered around a powerful female protagonists and told from theirs or the her own perspective. Perhaps having a female write the story gave it a more feminine touch that gave it a bit more agency, or the fact that the story greatly centers around a worshiping of divine femininity and female empowerment, that may have lost some of its agency had it been told by a man (Mitchell xi). Likewise, while many men were working to make their voices heard in the revivalist movement, they were often taken a bit more seriously than their female counterparts, who were often overlooked not only because of their Celtic identity, but also because of their gender, making them even more easily neglected, both in their roles during the movement and in the little that they had done that had been gathered from Celtic history already (Morris 98). In this way, it would make it understandable to have a woman give their interpretation of a strong female character that for centuries had been a prominent female role model, in turn acting as a voice for the oppressed female warriors of the revivalist movement and being that strong female model herself. In the end, both personalities contributed to the cause by offering both unique male and female perspectives that worked in harmony with one another to showcase both perspectives.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is clear just how influential Macleod really was in the revivalist movement, although she is not often credited with appropriately in all that she had done. Through reading and studying this one story alone, Macleod had evidently created a truly inspiring piece that was greatly summed up the trials and tribulations of the revivalist movement, as well as offered an interesting insight into the role of females within the movement.

Works Cited

Anderson, Robert. “University History Teaching, National Identity and Unionism in Scotland 1862-1914.” The Scottish Historical Review, vol. 91, no. 231, 2012, pp. 1–41. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43773885.

Brekalo, Sanja. The Discourse of Nationalism and Internationalism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel, Tulane U, 2001. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/54248957?accountid=13631.

Ferguson, Megan C. “Patrick Geddes and the Celtic Renascence of the 1890s,” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Dundee, 2011. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/20479214.pdf

Garbáty, T. J. (1960). Fiona macleod: Defence of her views and her identity. Notes and Queries, 7, 465-467. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/54685917?accountid=13631

Grilli, Elisa. “Funding and the Making of Culture: The Case of the Evergreen (1895–1897).” Journal of European Periodical Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 2016, pp. 19-43. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1920309610?accountid=13631, doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/10.21825/jeps.v1i2.2638.

Harris, Jason M. Folklore and the Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction. Ashgate, 2008. Print.

Ross, William Stewart. Women: her glory, her shame, and her God: by Saladin. W. Stewart & Co., [188-?]. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca.

Marcus, Laura, Michèle Mendelssohn, and Kirsten Shepherd-Barr. Late Victorian into Modern. Oxford UP, 2016. Print.

Mitchell, M. L. (2015). Saint brigid of ireland: A feminist cultural history of her abiding legacy from the fifth to the twenty-first century (Order No. 3712702). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1707689825). Retrieved from http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1707689825?accountid=13631

Morris, R. J., and Graeme Morton. “Where Was Nineteenth-Century Scotland?” The Scottish Historical Review, vol. 73, no. 195, 1994, pp. 89–99. JSTOR,www.jstor.org/stable/25530618.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.