The Emergence of the ‘New Woman’ in Evelyn Sharp’s “The Restless River”

©2019 Andrea Aguiar, Ryerson University

Introduction

Feminist writers and activists alike have been continuously fighting for the recognition of equal female power in society, especially compared to that of men. Throughout history, it is easily recognizable that women were not considered as being of any importance, since women were not seen as ‘persons’ until the year 1928 with the Person’s Case in Canada (Hughes, 258). Especially in the nineteenth century, ideals of the inferior woman were held and reproduced within society, as laws and ways of life were all tailored to meeting the successes of men (Ledger, 9). In this way, feminists, whom are identified as those in society fighting for the equality of women, faced various barriers when trying to get their messages across, as these new ideals were not accepted in the public eye. Evelyn Sharp delivers one tale of the difficulties of getting the feminist message across, dedicating her life to working with women and proving that women, especially the nineteenth-century ‘new woman’, were ready to make their mark in society. Through her fairy tale “The Restless River,” which was published in volume 12 of The Yellow Book, Sharp’s feminist ideologies are easily recognized, as is her perception of the new woman. This publication resulted in the subtle introduction of the new woman into society, having significance as being told through a fairy tale and published in this specific volume of this magazine. By building the characters and their dynamic with one another in the story, Evelyn Sharp delivers to her readers a tale of feminine power, alluding to The Yellow Book’s supporting of a feminine position and the upraise of the new woman to the public eye.

Fin-de-Siecle Feminism and the New Woman

The ‘fin-de-siecle’ refers to the end of an era, in this case being the later part of the nineteenth century, in which society was dominated by patriarchal thought (Ledger, 9). Feminist thought during this time was not accepted by the public, as these ideologies went against the traditional patriarchal ones that the foundation of society was built on (Ledger, 10). Despite this, the end of the nineteenth century was also the time that feminists began to deliver to society the idea of the ‘new woman’ and at the same time act on it, as exemplified by Evelyn Sharp. The ‘new woman’ refers to a woman in society that is self-made (Tanner, 5), whom does not rely on anyone to aid her in making her mark on society, especially through education and occupation, and one that is willing to make her mark in public (Tanner, 8). Similarly, the new woman was one that wanted equal rights under the British Empire, which at the time was dominated by masculine thought (Ledger, 94). The New Woman Movement was one that people were opposed to because of the opposition to traditional ideology (Ledger, 95), leading these feminists to be considered ‘mannish’ in society when they would not give up their fight for equality (Ledger, 96). This idea is reflected in both the women that are featured in works of the late nineteenth century, especially those published in volume 12 of The Yellow Book, and also in the feminists of this time themselves. Sharp educated herself and wrote stories that resulted in her publication, at the same time forming an organization to aid women during the first world war. Her heroines, especially the Queen of Nonamia from “The Restless River” exhibit the same ideals of being self-made women, allowing Sharp to introduce the public to this notion in her own way.

The Yellow Book: Volume 12

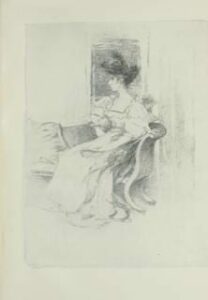

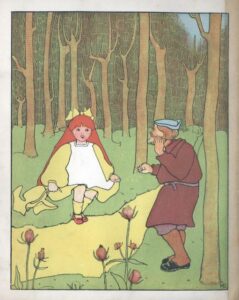

The Yellow Book was a publication, edited by John Lane, that was in print in London from 1894-1897 (Kooistra). The magazine featured works of both art and literature, publishing pieces that were often seen as controversial to the public eye (Kooistra). The Yellow Book was not a mainstream publication, resulting in minimal funding, but also a more selective readership that chose to engage with the magazine despite its contents and criticism it received from the public. Each volume has a theme that the selected works reflect, volume 12 being one example of this. This is the volume in which Evelyn Sharp published “The Restless River,” and through looking at the other works published in this volume, feminism is an easily identifiable theme. For example, a woman is pictured on the cover of the volume, and stories such as “Natalie” by Renee de Coutans and drawings such as “A Nursery Rhyme Heroine” by Ethel Reed are being published. This specific volume gave feminists of the 1890s a platform in which they could publish their works and expose society to their feminist messages. As it was not a mainstream publication, and the editors were not concerned with the social criticism the magazine received (Kooistra), these feminists were able to use this platform in order to be heard. It is noted that Sharp has most influence in this volume of the magazine, as her portrait, done by E. A. Walton is the first image and work featured in the volume. Her work as a feminist is celebrated in this volume, introducing readers to the feminist stance held by The Yellow Book as a whole.

The ‘1890’s Woman’ vs. The ‘New Woman’ in “The Restless River”

In her story “The Restless River,” Sharp uses her character, the Queen of Nonamia, to be her prime example of feminine power and the concept of the new woman, as exhibited through her actions and words. Similarly, Evelyn Sharp uses the relationships between her characters to demonstrate the feminine struggle for equality during the 1890s (Ledger, 95), which she experienced for herself as a new woman during that time.

Firstly, Sharp describes the Queen’s character as being an original woman who brought herself into her own position of power (167). As Sharp writes, “So the Queen of Nonamia had nothing to help her through life, except her own wits; she was not even beautiful, and her chief virtue was the patience she showed for the eternal stupidity of the Nonamiacs” (Sharp, 167). In the first page of this story, Sharp already paints her heroine as challenging typical traits associated with a lead female character, specifically those of a beautiful Queen that follows in her husband’s footsteps. As opposed to this, readers are introduced to a Queen that has not been assisted by anyone or any magical element alike, such as a Fairy Godmother, and one that holds more authority over the Kingdom of Nonamia than her husband does. Sharp presents readers with a reversed gender role association by giving the Queen the most power in the land (Ledger, 95), exploring the idea of men being the oppressed and silenced group in society as opposed to women. Her intentions become clear with the gender role reversal, as having a silenced male is more noticeable to readers of the time.

As the story progresses, we begin to see the Queen’s activity in the story, specifically through the influence that she has in her son’s life even before he is born. She wants to make sure that he will be original, as she is, and marry no one less than a princess, and so she orders that all of the woodcutters and their daughters be executed (Sharp, 171). The Fairy Godfather assigned to her son shares the fact that no one will be able to prevent his love for the woodcutter’s daughter (Sharp, 169), but the Queen continues to take it upon herself to have her son follow in her footsteps. She is fully involved in his life without him being aware of it, while at the same time ruling over the Kingdom of Nonamia and ensuring that everything is in order, according to her own standards. In this way, connecting back to the idea of the gender role reversal, the Queen is being painted as being controlling instead of being controlled. Rather than being subjected to the order of her husband, as women were during this time, she governs her son’s life and controls it as much as possible. This influences how readers view her character, as it is noticeable that Sharp is not trying to glorify her but instead make the gender relations of the real world known through her character.

As she brought herself to the position of power that she is in now, the Queen recognizes the importance of being self-made and ultimately being original (Sharp, 170), and wants the exact same for her son. The Queen models being active and working for what you want to her son, which are traits that he obtains himself. Eventually, the Prince is able to escape the confines of his mother, and despite his lack of education and knowledge of the world outside of the castle’s walls, he manages to find a way to break the enchantment that was set upon his one true love with minimal help. The prince’s lack of experience and knowledge is Sharp’s way of mentioning the same of women during the 1890s, but instead she presents it in a way that alludes a possible change to the reader. Although the prince was under his mother’s confines for most of his life, he managed to find a way to break free of them in order to find the love that he so desired, suggesting that women of the 1890s are also capable of breaking the confines set out for them by the patriarchy (Ledger, 94) and getting one step closer to becoming their own version of a new woman in society.

Fairy Tales and Feminism

Fairy tales, according to the Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (3rd ed.), are traditional folktales that are written down and altered for the purpose of entertaining children, typically involving elements of the fantastical that surround certain characters (Baldick).Through the story of “The Restless River,” readers can easily identify the fantastical elements and easily dictate how this story may be suited for children, considering its qualities of fiction. Despite this, Evelyn Sharp uses the fairy tale genre to her advantage when it comes to delivering her own feminist messages. Considering the fact that fairy tales are mainly for the purpose of entertaining children, the readers of fairy tales consider these stories to be entirely fictional, and thus the adventures that these characters are going on, as well as the characteristics that create this fictional world, come as less of a shock to the reader when they express ideas that are contradictory to common social thought of that time. Sharp does just this when sharing her feminist message through “The Restless River”; as it is a fictional tale, the readers of the story are not shocked when reading about a Queen who holds more power than her husband (Sharp, 168) or one that is constantly ready for action, despite the circumstances (173).

The readers will recognize these traits in the Queen’s character and admire them in the story, and in this way, Sharp is subtly introducing them to the idea of the emerging new woman in society. The Queen of Nonamia is a memorable character due to her choice of action and diction, and her character has the ability to influence both child and adult readers alike, giving them exposure to the idea that women in the real world also have the ability to hold and exude their own power, despite the overbearing patriarchy (Ledger, 94). Through this fairy tale, Evelyn Sharp discusses non-fictional concepts in a fictional way, but succeeds in her goal of getting her feminist message across. It is easy to identify that Sharp wanted readers to recognize this powerful heroine that she created, and at the same time recognize that this world, in which she dominates, is not entirely fictional after all. The reversed gender role is Sharp’s way of making obvious the barriers that women face in society, as they are more obvious when being placed upon a male character, allowing for her social critique while at the same time making her point that change can and will happen.

Conclusion

Through the publication of “The Restless River” in volume 12 of The Yellow Book, and while looking at the volume as a whole, it is easy to recognize that the publication itself supports a feminist stance, as it provides feminists with a place for their voices to be heard. This volume specifically shares works created by and about women, each individually containing subtle messages regarding the emergence of the ‘new woman’ and what she is able to do in society. Considering the readership of The Yellow Book, these messages were being shared to a variety of people of all genders and ages, exposing everyone to the new female power. Ideas shared by nineteenth century feminists, especially Evelyn Sharp, prove to be of most importance in the twenty-first century, as they paved the way for the emergence of the new woman and modern feminist thought. Since the time that “The Restless River” was published, women became recognized as people in society (Hughes, 258), and although they still face injustices of many kinds, women of the modern day live in a world in which they are able to have their voices heard and their power shown. Feminist thought continues to grow, as does the strive for equality that women experience in their everyday social realities, and it is because of the works of feminists like Evelyn Sharp that these ideas became known in the first place. As ideologies continue to emerge and women grow steps closer to being treated with equality in the public eye, it is because of the works of people like Sharp that every new woman is able to be their own Queen of Nonamia and have their voices heard.

Works Cited

Baldick, Chris. The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford University Press, January 1, 2008. Oxford Reference. Accessed March 2019. Web.

Hughes, Vivien. “Women in Public Life: The Canadian Persons Case of 1929.” British Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 2006, pp. 257-270.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “The Yellow Book (1894-1897): An Overview.” The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2012. Accessed March 2019. Web.

Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siecle. Manchester University Press, 1997.

Sharp, Evelyn. “The Restless River” The Yellow Book 12 (January 1897): 167-187. The Yellow Nineties Online, Ed. Denis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. March 2019. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV12_sharp_restless.html

Tanner, Clare. “Modernity’s ‘New Women’: Visual Culture and Gender Play in 1890s Australia.” Hecate: A Women’s Interdisciplinary Journal,vol. 37, no. 2, 2011, pp. 4. EBSCOhost,https://web-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=a01e937c-dbb0-4f14-86f1-de06ab9c27b9%40pdc-v-sessmgr05&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=ibh&AN=95573820

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.