The Representation of Women in Music Halls in “A Romance of Three Fools” by Ernest Rhys and “At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations” by Arthur Symons

©2019 Payton Flood, Ryerson University

Introduction

The Savoy was one of the most prominent little magazines of its time. With the Yellow Book’s recently ousted Arthur Symons and Aubrey Beardsley as its editors, The Savoy represents the aesthetic ambition of two of the most forward-thinking literary and art creators (Claes and Demoor). The two pieces I will be analyzing are “A Romance of Three Fools” by Ernest Rhys and “At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations” by Arthur Symons, both of which were published in volume five of The Savoy in September 1896. Rhys’ fairy tale uses satire to emphasize how working women in music halls are sexualized and demoralized by the audience who gives them fame, while Symons’ essay plays into society’s criticism of music halls by feeding into the double standards which condemn women performers. Music halls were extremely controversial in the 1890s, often being disparaged by “moral conservatives” because “the flouting of women’s bodies in combination with licentious words, gestures and costumes” was thought to lead to the sexual excitement of audiences (Davis 39). Rhys’ fairy tale takes a feminist approach in challenging society and Symons’ expectations of women and the reluctance to let women earn a living. Although Rhys’ narrative is told from male perspectives, he uses their voices to satirically highlight the judgments passed onto women performers.

1890s Britain and Popular Culture

During the 1890s, London was at its peak; according to Andrew Horrall, it was the largest and richest city, therefore, making it the most important metropolis in the world (1). Thanks to the industry and shipping from the Empire, London experienced rocketing profits across all markets, including popular culture. It was music halls that gave way to true entertainment success. Being an imperial capital meant an influx of countless performers who brought with them “foreign influences, idioms and ideas” and whose “new perspectives on popular culture” would be broadcast around the world (Horrall 1). Music halls originated from public-house evenings, where men and women would perform on table tops to be rewarded with free drinks; it was not considered a professional industry. Later, music halls were commercialized, and professionals wrote songs and skits to perform (Horrall pp. 1-2). Music halls became one of the most important modes of popular culture, as it was Britain’s “first entertainment industry” (Horrall 3). It was through the construction of entertainment venues like the Alexandra Palace, the Ally Pally, and the People’s Palace that the Victorian middle class and poorer Londoners were able to provide themselves with edifying leisure (Horrall 10). While provoking challenging alternatives to conservative progressivist views, music halls used their stages to evoke modern conversations about class, gender, national identities, and mainstream political issues (Platt and Becker 1). Because of their liberality towards sexuality and gender, music halls were criticized and defamed by upper-class members of the public. With new restrictions imposed on women’s costumes and religious sectarians procuring the deeds to halls in order to halt performances, many theatre managers began to question “how far ‘the moral sense of majorities’ would be allowed to dictate public access to art” (Davis 40). Then in 1889, the supremacy over music hall licensing was transferred to the London Country Council’s new subcommittee on Theatres and Music Halls, ultimately tipping the scale in favour of reformers (Davis 41). However, although access to popular culture was spread across London, parts of the population, and women, in particular, had a more limited access to private entertainment (Horrall 11).

Working Women

The quality of life among Britain’s working class was at an all-time high in the late nineteenth century; the living standards drastically improved, and patrons were able to properly enjoy the growing consumer and leisure culture (Parratt 22). The gender order of late-Victorian England saw that women not only had less access to leisure activities than men, but men would knowingly pursue leisure at the expense of their families’ welfare. Work became an integrated attraction in the lives of women, although they were denied equal access and fair wages for their labour. Much of the domestic work women were required to perform was illegitimized and industry jobs were unqualified, without job-protection, and low-paying (Parratt 25). For working-class women, the decision to take the stage was not a superficial one. In a society of over-crowded and unskilled labour markets, women were able to find expertise and validation in their theatrical vocation. Not all women were trying to become actresses, but they were all trying to earn their own living (Faulk 114-115). There is value in considering the motives behind Rhys’ decision to center his fairy tale on the pursuit of a female performer’s attention. If Marie Barrone was seeking the fame and attention assumed of her, readers would not expect her character to be as uncomfortable as she is with using Momus’ coachmen. In a conversation with Momus, Barrone also claims she needs a holiday to rest her voice, suggesting perhaps that she is overwhelmed by the devotion her occupation places upon her. After thanking the men for their support, Rhys writes, “her voice had that little quiver again” (59). This statement comes after Barrone has repeatedly tried to excuse herself from the conversation. Because she is a music hall performer, she is expected to entertain and therefore feels a sense of obligation to keep up her appearance and engage with the men, otherwise swift dismissal could have a negative effect on her career and her ability to make an income.

Women in Music Halls

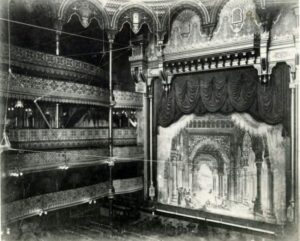

Female performers in late-Victorian music halls were victims of great condemnation. Often, these women were subjected to associations with prostitution and regarded as having low moral standards because of the costumes they wore and the characters they had to present themselves as on stage. Examples of the judgments passed onto female entertainers are replicated in both Symons’ “At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations” and Rhys’ “A Romance of Three Fools.” Symons uses his experience during a night at the Alhambra Theatre to explain the frenzy in preparation to the start of the show. He describes the illusion created by the wigs, make-up, and costumes of female performers. Symons reveals that make-up on an unattractive woman has no cause, but make-up on a beautiful woman serves to emphasize her charm. He states, “The very phrase, painted woman, has come to have an association of sin; and to have put paint on her cheeks, though for the innocent necessities of her profession, gives to a woman a sort of symbolic corruption” (Symons 77). The woman’s appearance and sexual aura, although created for the purpose of her performance, are seen as immoral and offensive to the high-class late-Victorians. Dancing allegedly prompted promiscuity and prostitution, creating local music hall controversies (Kift 155). Because these women presented themselves in a forward way, in front of large assemblies of the public, they were seen as both immodest and lower class. Respectable working women had domestic or industry jobs, they did not wear provocative clothing and present suggestive material to the community. Rhys uses his fairy tale “A Romance of Three Fools” to exemplify these uncharacteristic behaviours found in music hall women. The character of Marie Barrone uses her beauty to garner the attention of multiple men, and in a fairy tale-like manner, charms three different men into believing they are the sole proprietors of her affection. This stereotype plays into the indecency of music hall performers and is further upheld by complaints that a pair of American men were “being ‘continuously accosted by night and solicited by women’” during an evening at the Empire theatre (Faulk 79). Rhys later contradicts his earlier stereotypes when it is revealed that Marie is married to Mr. John Jones. The satirical irony of this event draws attention to the unsolicited devotion and gifts brought to Marie by Jack Momus because of her occupation, which therefore classified her as an exhibitionist. The assumptions placed on women in music halls speaks more of the society of late-Victoria than it does the performers. Because of the topics and their presentation, music halls were labeled as uncouth and provocative, subsequently subjecting those who performed and worked in music halls to those same labels. With such a high emphasis placed on the vulgarity of these popular events, the sexual excitement of the audience was a natural outcome that reflected the indecency of the clientele, not the performers (Faulk 3).

Late-Victorian Fairy Tales

Both “A Romance of Three Fools” and “At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations” use fairy tales within the stories to depict conservative, elitist opinions of popular culture music halls. Fairy tales were and are now generally meant for the entertainment of children, but in the 1890s, many adults began to indulge in the fantasy of these stories. These works can be categorized as fairy tales because of the spectacular events and characters. This is evident in Rhys’ story because Marie’s mannerisms and behaviour bare striking similarities to those of the famous Cinderella, a fact which is quite comical because of Miss Barrone’s portrayal of that exact character in the music hall production of “Sweet Cinderella” as is mentioned in the narrative. Momus can be likened to common characters of Prince Charming as he chases after the illustrious woman who has captured his attention. Using different locations, with each presenting their own challenges, readers are offered passage around the United Kingdom to experience the scenery alongside Momus. The same can be used to describe what Symons encounters at the Alhambra as he illustrates the varying sensations awarded to him simply by changing his position within the theatre. “A Romance of Three Fools” is more of a modern fairy tale that uses a man’s desire and his ignorance against him, in an effort to contradict assumptions about women. “At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations” can be classified as an essay that uses the music hall and fairy tales to play into the conservative, elitist mindset to criticize the middle-class leisure forms. Very few of the literary works found within volume five of The Savoy fall into the defined category of a fairy tale; other than Rhys’ work, Olivia Shakespear’s “Beauty’s Hour,” and an English translation of “O Petites Fées” by Gabriel Gillett from Frenchman Jean Moréas fall under this genre. This is because innocent and child-like themes contradicted the licentious and “flamboyant” reputation TheSavoywas attempting to establish for itself (Claes and Demoor 139).

Conclusion

Music hall performances were the most sexualized and provocative modes of popular entertainment of the 1890s. This resulted in their actresses being among the most degraded of working-class women professions. Authors like Rhys and Symons were able to use the decadent reputation of The Savoy to present their scandalous fairy tales in a way that was acceptable of that era. Rhys uses the fairy tale genre to satirically comment on assumptions placed on female performers in music halls and the uncomfortable advances they were subject to as a result of the sexualization of their occupation. Symons critique of the music hall gives an audience perspective of the actresses that sheds light onto how and why society views them as indecent. The Savoy was able to publish these works of such controversial topics because they coincided with themes readers expected to find in the magazine. The fairy tale genre was simply a tool used to make these works seem more appropriate to the conservatism of the late-Victorian era.

Works Cited

Claes, Koenraad, and Marysa Demoor. “The Little Magazine in the 1890s: Towards a “Total Work of Art”.” English Studies, vol. 91, no. 2, 2010, pp. 133-149. Scholars Portal Journals, doi: 10.1080/00138380903355049

Davis, Tracy C. “The 1890s: The Moral Sense of the Majorities: Indecency and Vigilance in Late-Victorian Music Halls.” Popular Music, vol. 10, 1991, pp. 39-39. JSTOR, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/stable/853008?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Ernest, Rhys. “Romance of Three Fools.” The Savoy, vol. 5, September 1896, pp. 57-69. Internet archive, https://archive.org/details/savoy02symo/page/56

Faulk, Barry J. Music Hall & Modernity: The Late-Victorian Discovery of Popular Culture. Ohio University Press, 2004.

Horrall, Andrew. Popular Culture in London c. 1890-1918: The Transformation of Entertainment. Manchester University Press, 2001.

Kift, Dagmar. The Victorian Music Hall: Culture, Class, and Conflict. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Parratt, Catriona M. “Little Means or Time: Working-Class Women and Leisure in Late Victorian and Edwardian England.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 15, no. 2, 1998, pp. 22-53. Scholars Portal Journals, doi: 10.1080/09523369808714027

Platt, Len, and Tobias Becker. “Popular Musical Theatre, Cultural Transfer, Modernities: London/Berlin, 1890-1930.” Theatre Journal, vol. 65, no. 1, 2013, pp. 1-18. JSTOR, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/stable/41819819?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Symons, Arthur. “At the Alhambra: Impressions and Sensations.” The Savoy, vol. 5, September 1896, pp. 75-83. Internet archive, https://archive.org/details/savoy02symo/page/74

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.