Influence of The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and The New Woman’s Movement in Laurence Housman’s “Tale of a Nun”

©2019 Elisia Steinberg, Ryerson University

Introduction

The Pageant, an art and literature annual with a print run from 1896 to 1897, was a magazine that reflected the avant-garde decadent and aesthetic movements popular during the fin-de-siècle. During this time, many revolutionary social and political movements had gained momentum. The New Woman’s movement advocated for the independence and autonomy of women trapped by the social conventions that held most Victorian women to an impossible standard of purity, obedience, and devotion to their husbands and fathers. The contents of the first volume of The Pageant (1896) show support for this feminist movement through their overt influence from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an earlier artistic movement that sought to represent women with sexual agency and personal power. This relationship is evident in religious folktale, “Tale of a Nun”, translated by L. Simons and Laurence Housman, the latter who was strongly influenced by the works of the Pre-Raphaelites and was a champion of women’s rights for sexual, social, and political freedoms in Victorian England. In this folktale, a nun escapes from her convent to wed, and mother children, eventually falling into poverty and prostitution. When she returns to her religious life, she is accepted without judgment or hostility, allowing her to be simultaneously both a sexual and a spiritual being.

Critical Claim

The choice Laurence Housman made to translate “Tale of a Nun” into English for The Pageant Vol. 1 was inspired by his artistic influence from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and by his quest for gender equality. Through this religious folktale, in which a chaste and pious nun falls into prostitution only to be welcomed back into religious life without shame or penance, is telling of Housman’s support of woman’s rights during the moment of production. The New Woman’s movement is particularly reflective of an important cultural shift taking place during Housman’s life; from women’s lives as extensions of men’s, to women as independent and autonomous beings with agency over their bodies and choices. This support of this cultural movement is reflected in “Tale of a Nun” through the archetype of the Pre-Raphaelite fallen woman, representing the possibility of women to be both spiritual and sensual, an ideal shared by both Housman and the Pre-Raphaelites.

Beatrice’s fall and rise in “Tale of a Nun”

In this folktale, a beautiful, hard-working, pious nun named Beatrice was consumed with a secret romance she had with a young lord who would visit her at her window. Before escaping with the young lord, Beatrice lays her things at the altar of the Virgin Mary and pledges her devotion. The couple remain comfortable until their money runs out, after which the young lord leaves Beatrice and their two children alone. Beatrice enters a sinful life, causing her much distress and sadness. Fourteen years later, they take shelter with an old woman, who has already heard of Beatrice’s noteworthy devotion to God, citing her as an example of pureness and holiness. Beatrice prays again to the Virgin Mary and gets a response from above, encouraging her to return to the convent. She prays two more times to be sure of this message which is twice repeated. She leaves her children with the old woman to be taken care of and returns to the convent, where her things wait for her before the statue, just as she left them. An abbot arrives at the convent for the nuns’ confession and the nun confesses all of her past transgressions. The abbot offers her remission from her sins, and in his next sermon, he makes an example of Beatrice as proof of the Virgin Mary’s unwavering love.

Cultural Context and Gender Politics

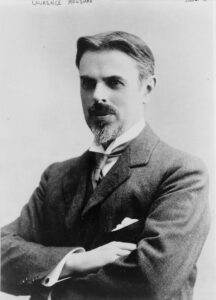

Laurence Housman (1865-1959), the artist and writer who translated “Tale of a Nun” for The Pageant Vol. 1, lived during a time of vast social change. The nineteenth century’s economic boom resulting from industrialization brought the expansion of the middle and professional classes and led to changes in patterns of work and family life (Barringer 17). As a result, progressive calls for social reform, such as The New Woman Movement, which spanned from 1890-1920, began to garner momentum. The New Woman Movement was a revolutionary feminist movement during the turn of the century, which encouraged health and dress reforms, promoted women’s suffrage, and prompted society to begin to perceive women as intelligent, independent, and able to work, study, and socialize on par with men (“New Woman”). In Victorian England in the late 1800s, the passive lives of women were mostly understood in relation to the active lives of men, whether it be their husbands or fathers, ultimately confining her scope to the inner world of the family and home. Supporters of The New Woman Movement subverted this expectation through literary and artistic representations of women trapped by social conventions, their lives devastated by lack of choice, and through reimagining history and myth from feminist perspectives (“New Woman”). The Pre-Raphaelites also sought to reimagine history and myth, through the retelling of religious narratives from new perspectives. Similar to the artistic representation of The New Woman, this group of artists desired to depict women who suffer at the hands of their social and cultural environment, sometimes reflected in their commonly used archetype of the fallen woman. In “Tale of a Nun”, this archetype is reflected in the character of Beatrice, who due to economic needs, subverts the social norms that would require her to remain a chaste and pure woman, and is still welcomed back into a house of God with allowing both spirituality and sensuality to reside within her.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed in 1848 by seven artists, including Dante Gabriel Rosetti and John Everett Millais, both whose artwork is featured in The Pageant Volume One. Their goal was to liberate art from triviality and to use it as a mode of political and social commentary. Issues of labour, illegitimacy, and the taboo subject of prostitution were explored in their work, reflecting social, political, and economic concerns relevant to the times they lived in (Barnes 14). In a moment of rapid urban and commercial expansion, the population of Victorian England expanded without adequate housing or sanitization, leaving prostitutes mainly confined to the slum districts which became synonymous with filth and disease (Marsh 77). In Victorian England, prostitution was defined as “the great social evil”, which created moral panic as a result of standing in direct contrast to the pure and idealized romantic love approved by polite society (Marsh 77). This dichotomy is what makes the representation of the fallen woman by the Pre-Raphaelites so radical for their time; In the context of Victorian representation of femininity, the presence of women with overt sensuality is directly at odds with the chaste ideal of VIctorian womanhood.

The Fallen Woman

The Pre-Raphaelites Brotherhood had a fascination with the archetype of the fallen woman. Described by Jan Marsh as, “the seduced girl. Adulterous wife, kept mistress, courtesan, harlot, or common prostitute”, these women were at odds with the social norms that kept most Victorian women as either virgins, wives, or mothers (77). The later New Woman Movement fought to give women sexual freedoms. They strove for acceptance for women in English society as valuable and respectable, while also having the liberty to be sensual beings. The double-standard of morality was exposed through the Pre-Raphaelite depiction of the fallen woman by showing these women through a lens of compassion and understanding. In shining light on the lack of accountability placed on the men who visited prostitutes, accountability which often fell upon the prostitutes themselves, The Pre-Raphaelites encouraged new ways of perceiving women who in the context of Victorian England would simply be demonized. The Pre-Raphaelite fallen woman offered an enlightened approach to the issue of prostitution, representing her as a symbol of innocent suffering, and a result of socioeconomic hardship rather than immorality. In “Tale of a Nun”, this archetype is used to reflect the new ideals of women’s rights that were being promoted contemporary to The Pageant’s moment of publication. The folktale illustrates a religious woman revered for her piety and dedication, forced to sell her body in order to support her family, and she is not thrown away for that. In fact, she is actively is allowed to resume a dignified religious life. Housman’s inclusion of this folktale in The Pageant reflects the progressive ideals of sexual liberation and female independence emerging at the time of production, his work binding together the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and The New Woman Movement.

Laurence Housman’s Pre-Raphaelite Influence

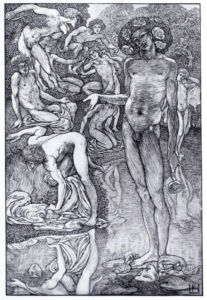

Housman was radically progressive for his time and spent much of his life advocating for women’s rights and social justice. As a huge supporter of the Suffragette movement, Housman, along with Henry Nevinson and Henry Brailsford, founded “The Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage” in 1907 (Doussot 143). After meeting Charles Ricketts in 1880, who encouraged Housman to move towards a more detailed style of illustration akin to the Pre-Raphaelites, Housman flourished as an artist and became well known for his work in the Pre-Raphaelite tradition. Housman advocated for sexual freedom and tolerance, his quest for harmony and greater equality, and his Pre-Raphaelite inspiration reflected in his work. Like the Pre-Raphaelites, Housman was unafraid to question societal norms and to produce art that challenged the conventions of his time. His artwork included subversive elements like “the grotesque” and “the male nude”, the latter reflected in a pen drawing included in The Pageant vol. 1, entitled, “Death and the Bather”, which depicts a sensuous male nude figure (Doussot 142).

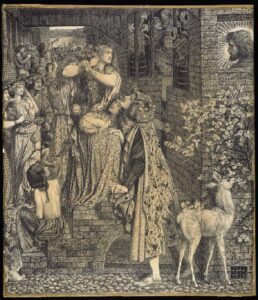

Housman was a homosexual and was therefore othered in his society as a result of Victorian English social norms of gender and sexuality. His choice to translate a religious folktale that represents a fallen woman being embraced by a loving higher power reflects his desire for acceptance of otherness, and his quest for equality and compassion. This goal was further reflected in The Pageant vol. 1 as a whole, specifically in regard to the issue of female equality and sexual freedoms brought forth by The New Woman Movement. The archetype of the fallen woman made other appearances in The Pageant Volume One in addition to “Tale of a Nun”, advancing the goal of representation of strong and capable women with sexual agency. For example, the Frontispiece of the magazine, which is the artistic introduction to this magazine as a whole and is representative of its overall themes is an illustration by Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti, titled Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting. This is an example of a fallen woman depicted by the Pre-Raphaelites, bridging sensuality and spirituality, themes that follow very clearly in Housman’s “Tale of a Nun”.

Finding Connection and Support in the Quest for Women’s Rights

For his time, Laurence Housman was quite a radical character. His identity as a feminist and pacifist reflected the social progress that occurred during his lifetime, and greatly influenced his artistic and literary pursuits. His inspiration from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood encouraged a bridging of past and present in his work, the social ideals of an older artistic movement mirrored in the social ideals of a contemporary fight for equality. One can imagine the progressive female readership of The Pageant, feeling inspired and justified by witnessing the principles of The New Woman’s Movement echoed in a text that came from long before their own time. The Pre-Raphaelite influence on Housman influenced his decision to translate “Tale of a Nun” for his audience, using the Pre-Raphaelite archetype of the fallen woman reflected in Beatrice to encourage support for female independence and sexual liberation. By retelling a very old text, with an archetype used by a newer artistic group, in order to promote social ideals contemporary to him, Laurence Housman sets the theme of womens rights in a larger historical context, creating connection and inspiration in his readers.

Works Cited

Barnes, Rachel. The Pre-Raphaelites and their World. Tate Gallery Publishing, 1998. “Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee”. The complete Writings and Pictures of Dante Gabriel Rosetti: A Hypermedia Archive. 2000-2007, http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/s109.rap.html

Barringer, Tim. Reading the Pre-Raphaelites. Yale University Press, 1998.

Doussot, Audrey. “Laurence Housman (1865-1959): Fairy Tale Teller, Illustrator and Aesthete.” Cahiers Victoriens & Édouardiens, no. 73, April 2011, pp. 131-145. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/878055251?pq-origsite=summon.

Housman, Laurence and L. Simons, translators. “Tale of a Nun.” The Pageant, vol. 1, 1896, pp. 95-116. The Yellow Nineties Online, edited by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Center for Digital Humanities, 2018, https://archive.org/stream/Pageant1896_201609/Pageant1896 – page/n135/mode/2up/search/tale+of+a+nun.

Marsh, Jan. Raphaelite Women. Phoenix Illustrated, 1987.

“New Woman.” The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States, edited by Cathy Davidson and Linda Wagner-Martin, 1995. Oxford Reference. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/view/10.1093/acref/9780195066081.001.0001/acref-9780195066081-e-0581?rskey=pb3FGQ&result=1

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study or education