Diversity in Gender via Genre in Vernon Lee’s “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”

©2019 Lana Bosnjak, Ryerson University

An Introduction to The Yellow Book: an Avante-Garde Quarterly

The Yellow Book was published by John Lane of “The Bodley Head” publishing house; its literary and art editors were Henry Harland and Aubrey Beardsley, respectively. Issued seasonally from April of 1894 to April of 1897, The Yellow Book consisted of 13 volumes and was priced at 5 shillings a volume (comfortable for the middle-class). The London-based periodical was marketed in America and the British Isles, though readers and contributors—both established and new—came from various European countries and the English-speaking world. This literary magazine included short stories, poetry, non-fiction memoirs, essays, review-essays, and stand-alone works of art. The Yellow Book was progressive in its content and style; the conservative and patriarchal Victorian expression of art and literature was not reflected in this fin-de-siècle publication, but rather contrasted with diverse contributions that reflected forward-thinking social views. Due to Beardsley’s association to homophobic behaviour pertaining to Oscar Wilde’s arrest and trials, he was fired from his position as art director in April of 1985. This resulted in The Yellow Book, a formerly avant-garde magazine, seemingly shifting to a slightly more conservative period during the production of Volume 10. However, scholars today have shown that regardless of the transition caused by Beardsley’s firing, this decadent periodical remained innovative literarily, artistically, and conceptually (Kooistra). At the time of Volume 10’s release, public reception expressed praise for the literary content. The National Observer specifically accredited Henry Harland’s “The Invisible Prince” for being the best story in the volume for its “all too exceeding cleverness”, and gave Vernon Lee’s “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” criticism for extensively detailed descriptions, but ultimately complimented the charm and beauty of those very descriptions in addition to the “freshness and humour” (Yellow and Green). Conversely, the visual content of this volume was not met with the same enthusiasm— insulted and claimed to fare poorly if not for the works of Stanhope Forbes and D.Y. Cameron.

Female Presence in Volume 10

In accordance with the periodical’s consistent fin-de-siècle approach to conflicts of its era, The Yellow Book’s 10th volume is especially progressive in its representation of women. Volume 10 is the first of its publication to include more female contributors than male, which reflects an opposing stance on the otherwise popular ideal of Victorian women fulfilling a domestic role. In addition to representation through presence, the actual subject matter of the creative content provides commentary on gender politics within the contemporary world through literary works such as love poems, ghost stories, and the aforementioned “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” by Vernon Lee. This fairy tale exhibits androgynous representations of gender by no coincidence, as it is extremely relevant to her private life. Visual art in Volume 10, such as the critically well-received piece by Stanhope Forbes: “A Dutch Woman” also provides commentary on the role of women. Sketches in this volume, like Forbes’, often show women as maids, though the contributors themselves defy this traditional concept of womanhood. Despite Forbes’ career as a visual artist, this piece contrastingly depicts the titled “Dutch Woman” in a domestic setting—a space she herself does not occupy but is expected to as a woman in the 1900s.

Vernon Lee: The Published Voice of Violet Paget

Vernon Lee, a pseudonym for the female essayist and theorist Violet Paget, was born October 14, 1856 in France, and published actively between 1880-1933 (before passing February 13, 1935). Her work covered a wide range of topics: critical and theoretical essays on the arts; short stories and a novel often reflecting on the cultural status of art; and psychological theories about the perception of form in the visual arts, literature, and music. Although “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” is Lee’s only contribution to The Yellow Book, various works of fiction similar to its genre were authored under the same name prior to the publication (Denisoff and Kooistra). Lee gathered popularity in London literary circles, but quickly offended the Pre-Raphaelites—that had thus far offered support— through personal perspective on pleasurable aestheticism that did not agree with British aesthetes (who she saw as sensualist). With her lover, Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, Lee published results of studies pertaining to the psychology of aesthetic experience in which minute physical responses in the human body were triggered by formal visual pleasures in art. This study, among many of her books published in the later 19th century, resisted popular aestheticism. The shift in her attention to psychological aesthetics resulted in trouble finding support in readership. Later, in the 20th century, critics and theorists initially marginalized her, but developed to sum the public obscurity of her original aesthetic theory to the personal and cultural prejudices of her time (Morgan). As a lesbian and a writer, Paget’s existence in the Victorian era strongly contradicted the traditional ideology of women of the time period; as such, she was dedicated and prolific in her writing on sexuality, gender roles, and Aestheticism. As a Decadent Aesthete, it is with little surprise that she identified with this arts movement to express opinions rejecting the patriarchal status quo of the 19th century.

Aestheticism and Decadence

Aestheticism is a 19th century movement that revolves around the idea that works of art have value to the extent that they may be appreciated for their aesthetic merits alone, separate from reference to anything outside of itself. Aesthetes value art for aesthetic value and believe that said value is not derivative from any other kind. They argue that art belongs in the realm of aesthetic, and that very realm has a wholly autonomous value. (Janaway). Vernon Lee’s association with this movement may seem contradictory to her cause as a someone who produced work expressing strong objections to social hierarchies of her time specifically in regard to gender and sexuality. This is where Decadence comes into play.

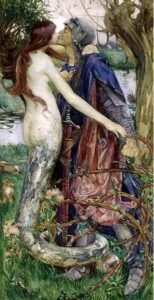

Within Aestheticism, the Decadents were artists who did not identify within traditional social structures. As a result, this movement produced art that unapologetically rejected the cultural norm. A form of neoclassicism, Decadent art pulled from Greek and Renaissance forms as well as content. Artists would pull inspiration from these texts and create their own stories, altering classical contexts with their own marginalized perspective in order to manifest and legitimize their experiences. These movements and the individuals within thrived in the fin-de-siècle, seen through the success of Decadent Aesthetic writers such as Oscar Wilde, The Yellow Book’s very own Henry Harland, and many others. For Vernon Lee, her space in the Decadent community allowed for expression of personal beliefs pertaining to sexuality and gender roles, as a lesbian writer in a patriarchal society. Lee’s ability to blend genre creates discomfort, due to breaking off from classical modes of presenting written work. This reflects her break from classical notions of gender and her challenge to patriarchal establishments within literature (Zorn 63). In “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”, her generic choices mirror her theories of Decadence and gender roles through the ambiguous uses of genre and the ambiguous content of the work itself: the androgynous Snake Lady and traditionally immasculine Prince Alberic.

“Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”

In this story, readers are introduced to young effeminate Prince Alberic. Alberic is sheltered within the Red Palace—alluded to be somewhere in Italy—living with his grandfather, Duke Balthasar. As he is heavily neglected by his family, his only means of learning about the real world beyond the Red Palace walls is through fantasy within a tapestry depicting the fable of Lady Oriana the Snake Lady and his ancestor, Alberic the Blond. The fable tells of Alberic the Blond discovering a magical castle where he encounters an inscribed story about the cursed fairy Oriana. Oriana had been turned into a snake, and in order for the curse to be broken, she must be kissed thrice to return to her natural state. However, this transformation is only momentary. For permanent freedom, the prince must remain faithful to her for ten years. Alberic the Blond brings the fairy to her natural body but fails in remaining faithful for the full following decade. Upon hearing the story from a travelling storyteller, Prince Alberic attempts to succeed where his ancestor failed and brings Oriana back to her fairy state. Shortly after Oriana’s transformation, however, the Duke discovers that his grandson is in consorts with a powerful snake and kills her in confinement. Horrified and stubborn, Prince Alberic denies food for the two weeks that follow the murder, and, naturally, dies of starvation.

Genre-Blending and Real-Life Application

“Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” is an excellent example of Vernon Lee’s aesthetic writing accompanied with a Decadent approach of blurring the lines of what was culturally appropriate during its time of publication. This story challenges the readers perception of reality, both in the fading distinction of Prince Alberic’s reality and fantasy as well as the contrasting expectation for the story’s ending based on its generic elements. A fairy tale with gothic and medieval romantic themes, readers unfamiliar to the no-happy-ending-required convention of Decadent writing are thrown off-guard by the gruesome end to Lady Oriana and Prince Alberic’s love story that was otherwise delivered in pleasant, aesthetically beautiful prose. This disappointing end to a romantic endeavor reflects Lee’s personal life; homosexual relationships were socially frowned upon, therefore disappointing in a lack of overt exploration through social oppression. Appropriate to the neoclassicism in Decadent writing, this story also features mythological elements in its inspiration from folklore. Lady Oriana the “Snake Lady” closely resembles the serpent-like Lamia from Greek mythology, and her resulting androgyny ties into Lee’s own ambiguity of sexuality and gender. Furthermore on the physical state of Oriana, as a story within the fairy tale genre, “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” possesses the ability to delve into the supernatural. Female Victorian writers, especially during the fin-de-siècle, often explored supernatural phenomenon in fiction as a means to express socially unaccepted hidden desires—particularly desires related to sexuality or gender (Liggins 37). The fairy tale genre allowed for female writers—like Lee—marginalized by feelings of otherness to explore their desires, deemed unnatural by the general public of their reality, in a safe space of fiction.

Conclusion

The British 1800s fin-de-siècle was revolutionary in its dichotomization of cultural beliefs. With advances in science, social structures based on religion were more critically observed and questioned, especially in regard to gender politics. Popularity of Aestheticism and Decadence furthered criticism of traditional beliefs. It challenged the status quo of gender and sexuality and pushed art to be viewed as a sensual experience to be valued for its beauty rather than a tool to inspire morality. Through artistic publications like The Yellow Book, these movements were able to share their perspectives amongst the masses, gaining following for their otherwise marginalized voices. Though not overt, these perspectives can be found in generic choices made by creative contributors. As seen in Vernon Lee’s “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”, utilization of fairy tale, romantic, gothic, medieval, and mythological genres in the Decadent style communicated the personal challenges of androgyny, failed romantic expectations, and marginalization she faced as a queer working woman in the Victorian patriarchy. Although there is much diversity in the artistic style and genre of contributors to The Yellow Book, these choices of delivery contribute to the articulation of the artists’ social commentary.

Works Cited

Denisoff, Dennis and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. ” The Yellow Book: Introduction to Volume 10 (July 1896).” The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV10_Intro.html

Janaway, C. “aestheticism.” The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. : Oxford University Press, January 01, 2005. Oxford Reference. <http://www.oxfordreference.com /view/10.1093/acref/9780199264797 .001.0001/acref-9780199264797-e-34>.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “The Yellow Book (1894-1897): An Overview.” The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2012. Web. http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB_Overview.html

Liggins, Emma. “Gendering the Spectral Encounter at the Fin De Siècle: Unspeakability in Vernon Lee’s Supernatural Stories.” Gothic Studies, vol. 15, no. 2, 2013, pp. 37-52.

Morgan, B. “Lee, Vernon.” Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. : Oxford University Press, January 01, 2014. Oxford Reference.<http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199747108.001.0001/acref-9780199747108-e-454>.

“Yellow and Green.” Rev. of The Yellow Book 10. National Observer 15 August 1896: 393-4. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=review_v10_national_observer_15_aug_1896.html

Zorn, Christa. “Between the Lines of Gender and Genre.” Vernon Lee: Aesthetics, History, & the Victorian Female Intellectual. Ohio UP, 2003, pp. 60-75.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.