Celtic Revival, Paganism and Birth In “The Unborn”

© Copyright 2019 Eden Abraham, Ryerson University

Introduction

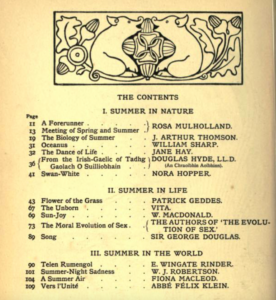

The Evergreen was one of the few magazines of its time to promote and embrace nature in all its organic glory, inspiring the celebration of every aspect of natural life. It fills itself with a myriad of different texts, including short stories, long stories and imagery, each piece reflects the theme of nature. Taking a particular interest in the text “The Unborn”, I decided to research how this peculiar story about a baby in its womb contributes to the goal of the Evergreen. Looking through the critical lens of Celtic spirituality and naturalism, we can see how the text’s depiction of birth and familial bonds plays a significant role in the Evergreen’s mission of political and cultural renewal of the Scottish tradition, as the story ultimately represents the Celtic Revival itself.

The Evergreen: A Mission for Cultural Renewal

In order to understand “The Unborn” as well as the other texts, the investigation of the Evergreen itself is imperative, including what motivates it, the authors, and its ultimate purpose. The Evergreen was a little magazine published in 1895 which intended to uphold Scottish tradition and inspire political and cultural renewal in the Victorian era. Through unique tactics such as using hand-painted manuscripts for its wood-engraved material, the magazine historicized and politicized the Victorian periodical by reclaiming forgotten Celtic roots (Kooistra). One of the first of its time to commemorate the Scottish Renascence, the magazine also used metaphors of natural harmony to integrate aesthetic and its sociopolitical concerns (Claes). Unique from other little magazines that focused on poetics or politics, the Evergreen separated itself into 4 volumes, each themed by one of the four seasons, its cyclical process representing life’s natural movement and rhythm and reflecting a natural systematic harmony, each piece contributing to the unity of the whole. In natural spirituality, it is believed that the natural world follows a Law of Cycles, which can pointedly be seen in the changing seasons of the year and the cycles of life, death and rebirth. It is this cyclical rhythm that keeps everything balanced, maintaining equilibrium and harmony in the natural world (Lincoln).

Author Patrick Geddes situates the magazine in a cycle of renewal, but his deeper purpose lies within the building of human relationships rather than seasonal change (Kooistra). He believed all experience of life should increase our awareness and appreciation of nature and community. Hand-in-hand with Celtic religion, spirituality and tradition, this intimate relationship between humans and natural elements are important aspects of old Scottish culture. The Celtic Revival, which directly motivates the work of “The Unborn” in my interpretation, aims to rekindle this spiritual connection between people and the natural world, a sense of creaturehood, the belief that we are not alone in the world, and the belief that we enter a relationship with a benevolent spirit world (Duncan). Geddes also emphasizes the artistic treatment of the human condition and our personal relationships to the natural world to help combat the detachment of science; the magazine’s aim was not to present scientific research and findings as a goal itself, but to show how the insights of the texts can help us feel at genuinely home in this world (Claes).

Geddes viewed art as a “necessarily collective effort that reflects the historical traditions of the community of the community that produces it” (Claes), and that this should unite inspire coherence within said community. The Evergreen’s use of the seasons manifests the inescapable influence of nature on the individual as well as the community, and acts as an integral organic element to the magazine’s presentation. As well, controversial for its time, the Evergreen did not patronize artistic and literary decadence, but chose to subscribe to a sociological point of view that locates this phenomena within a wider set of social problems; the texts often highlights the sufferings of different social classes, addressing issues with unsuitable living and warped social relations that disrupt the way they see the world (Claes).

Investigating the Evergreen’s history, contextual motivations and authorship build the foundations to better interpret and understand “The Unborn” and how it contributes to this cultural renewal.

The Unborn

“The Unborn” is a text in the third volume of the Evergreen located the “Summer in Life” section, and it explores the process of change and transition through the perspective of a baby who must reluctantly exit the womb. For a majority of the text, the story is presented as a dialogue between the baby and its brother who is outside the womb, encouraging him to enter life with him so he can experience all the wonderful aspects of life: light, the sun and the blue skies, and the beauty of knowing family. The baby rejects the brother’s persuasions and this unknown new world, determined to stay inside the womb where it’s familiar and safe. As the baby is inevitably born, it is instantly happy and smiling after being held and breastfed by its mother for the first time. The Unborn becomes the Born, having entered the natural world full of family and nature, and is finally in its true home.

With an unknown author, biographical information is not a source that can be used in the text’s interpretation, but the appropriately chosen pseudonym Vita (meaning “life”) speaks to the greater implications of this work. Rather than authorship being an element of focus in its interpretation, the use of a pseudonym allows readers to read and explicate the work on their own terms without the influence of a writer’s background. As will be explained later, this shifting of authorship and responsibility onto the audience affects the way the text is received, as it pushes them to be active participants in the story’s message and outcome.

Birth as a Symbol of Naturalistic Transition

With birth being a large part of the story’s progression, I decided to investigate how the text uses the phenomena to support the Evergreen’s ideals. Reading the text through the lens of Celtic spirituality, it is evident how “The Unborn” parallels the beliefs of paganism and Celtic Revival through the presentation of birth as a natural and spiritual transition from one period of life to another. The protagonist is a baby inside a womb who refuses to come out because his current home is familiar and safe, and his brother tries persuading him by telling him of all the beauty life has to offer and to “Give Nature her way and come forth”. This use of birth to depict someone going from a dark, lonely and stagnant cave into a bright, natural and beautiful world full of love and warmth reflects the desire for naturalistic and Celtic spiritualism to be reinstilled within the Scottish community. It’s also important to remember that birth and rebirth are key examples of natural cyclical rhythm within the Law of Cycles, its process believed to maintain harmony and equilibrium within the world (Lincoln). The first couple lines of the text said by the brother, “Come forth, my brother, to life, in the free and the open world; Come forth into light with me—and learn what ‘rejoicing’ means!”, is the text’s way of persuading the reader as well as the baby to join the “free” and “open” natural world.

The representation of both characters’ worlds, as well as their stark differences, speaks to the spiritual perspective of a Celtic and non-Celtic lifestyle. The baby is being enticed to join him in his world so he can know “of good and of truth and of beauty beyond compare”, and the main thing the brother relays to the baby is all the aspects of nature he will soon experience. The brother describes “The suns and the blue of skies”, and says: “Even if life brings wailing,—the sorrow it brings shall bless; Shall redeem and transfigure all Nature, watching to welcome you home. For life is a mighty breathing, a breathing of fresh, sweet air;”. Nature’s beauty is what the text uses to persuade the baby to join the outside world, which parallels the paganist motivations of naturalism.

It is also notable the text’s use of language, as it is revelatory of its deeper meaning and perspective. Throughout the story, the text chooses words like “free”, “open”, “dazzling”, “truth”, “light”, “good” and “home” to describe the world of the older brother, and “dark”, “shadow”, “safe”, and “shelter” to describe the world of the baby. This idea of an authentic reality is introduced and challenged by both the baby and his brother, both believing their worlds are “real” and a more suitable environment (however, it’s notable that the baby is clearly just struggling with the fear of leaving its familiar home to enter a foreign one, saying “My home is within the shadow, where none of these things [dangers] are known”), but the brother character is constantly appealing to the baby by describing the beauty of nature he will soon experience. While the baby does rejects all positive notions of the brother’s world, saying that it “dread[s] such a dangerous world, Full of cloudlands and lonely places:—” and “I am safe as I am and quiet; it hurts me to stir or move; This is all the Life I can bear. . . . .”, its eventual happy integration into society reveals which of the conceptual homes are better: the one full of love, sunshine, and family.

The Use of Family & Nature

“The Unborn” uses family to parallel with nature in order to convey the idea that they are both inherently desirable. Throughout the text, the sibling gives loving brotherly advice about not only the beauty of nature the baby will experience once born, but also the rejoicing of family; the brother tells the baby that once it comes out, “what ‘brother’ can mean shall be plain:—Brother and sister and friend: father and mother and wife. . . .”, implying that family is the most special and important aspect of life to experience. It paints nature (more specifically, elements commonly associated with Summer) and the outside world as a “true”, beautiful and welcoming thing while also associating it with the warmth, beauty and loving comfort of familial bonds. It subtly parallels and presents both these elements as something intrinsically good, and shows this by having the previously reluctant baby finally laugh in delight after being held and breastfed by its mother. Through the baby’s tumultuous process of birth, the wise and experienced insight into life given by the supportive brother, and the climax scene where the baby is finally where it belongs — in the arms of its loving mother — the Celtic principle is set. It shows how family always has your best interest at heart, and will always make you feel safe, just as nature is inherently meant to, as well. In terms of the Celtic religion, the mother character can also represent the spiritual faith and worship of the Goddess or Mother Earth, symbolizing the once-reluctant baby’s transition into the natural world. (Duncan). With the story’s end, the reluctant Unborn turns into the accepting Born through this natural transition, adopting the naturalistic ways of life and keeping the beating heart of Celtic spirituality alive.

All of these insights help understand how the text reinforces traditional Celtic (and inherently paganist) beliefs, and uses the process of birth to symbolize the transition and acceptance into a new naturalistic way of life.

Impact of Celtic Spirituality and Naturalism on Readers

Inspired by and representing the Celtic revival, “The Unborn” presents the natural world to be an ideal and intrinsically good, but its final block of text takes a shift in terms of its narrative. Its final lines read the following: “As the years went on and he grew, and could walk, run, think, and speak, Did he miss the dark life he had left? Would he fain have returned to that? Was the life he had entered less real? And was it fuller or not?” The story ends open ended, offering the reader a set of rhetorical questions which allow them to question the naturalistic process it’s presented and ponder whether or not this transition was the right decision. It diverges from its own set of beliefs and perspective by giving the audience authorship and the responsibility to decide the validity of this change, making them an active rather than passive participant in the story.

This turn of events in the text ultimately makes readers question their own transitions in life and question whether or not the tumult they experienced was worth the new life they began living. It takes a very sociological perspective on struggle, change and outcome, attempting to connect to a wider range of issues that readers could be facing. Much like Geddes’ emphasis on the artistic treatment of the human condition, as well as the use of artistic and literary decadence to speak to social issues like work environemts, gender discrimination and economic unstability, “The Unborn” connects to the personal problems of its audience through the framework of the larger Celtic revival and inspire introspection. As previously mentioned, Geddes’ aim was to show how the texts’ insights can help one feel genuinely at home in this world, and “The Unborn” reflects this desire. “What we need today are insights and spiritual practices that remind us of the Unity of our origins and that further nourish the longing for peace that is stirring among us” and Celtic tradition offers these to us while also “being deeply aware of the disharmonies within and between us that shake the very foundations of life” (Béres).

Apart from its promotion of paganist beliefs, “The Unborn” acknowledges the unsettling nature of the human condition that comes with change and transition, and invites the reader to unpack this commonly shared dilemma through the baby character. Being able to easily understand birth as a natural process of transition into, quite literally, a new and unknown world, makes the existential message and insight more digestible and processable to the audience, making the story better received. Both worlds presented in “The Unborn” show how the integration of nature and spirituality in the human experience can change how one feels about the physical space of a place (Béres), which is part of why the siblings expressed such different opinions about their worlds — although, the baby’s perspective was influenced/biased due to fear of the unknown new world, which also represents how blind people can be when they fear change from stagnation. The naturalistic way of life compels people because of the peace and harmony it provides, and “The Unborn” frames the tradition of Celtic spirituality as something we can learn from because it can help us understand ourselves and others.

Works Cited:

Béres, Laura. “A Thin Place: Narratives of Space and Place, Celtic Spirituality and Meaning.” Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, vol. 31, no. 4, 2012, pp. 394–413. Scholars Portal Journals, doi:10.1080/15426432.2012.716297.

Claes, Koenraad. “‘What to Naturalists Is Known as a Symbiosis’: Literature, Community and Nature in the Evergreen.” Scottish Literary Review, 22 Mar. 2012, http://link.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/apps/doc/A298614199/LitRC?sid=googlescholar.

Duncan, Graham. “Celtic Spirituality and the Environment.” HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, vol. 71, no. 1, Oct. 2015, p. 10. hts.org.za, doi:10.4102/hts.v71i1.2835.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. “The Politics of Ornament: Remediation and/in The Evergreen.” ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 41, no. 1, 2015, pp. 105–28. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1353/esc.2015.0004.

Lincoln, Kim Andrew. A Golden Age Economy. Troubador Publishing Ltd, 2017.

Vita. “The Unborn.” The Evergreen: A Northern Seasonal, vol. 3, Summer 1896, pp. 67-68. Yellow Nineties 2.0, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2018.