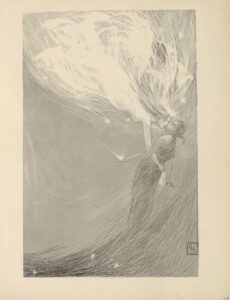

How Charles Ricketts Uses God | Analysis of Charles Ricketts’ “A Glimpse of Heaven”

Glimpsing Heaven

Many artists and authors make use of Christian symbolism or metaphor in their work to make a grand statement about societal behaviours, human nature, or to explain an arbitrary concept in a cryptic way. In his work “A Glimpse of Heaven,” Charles Ricketts can be compared to these artists through his use of Christian metaphor to make a point about the human experience with art in a time when the meaning of art’s existence was questioned. I will be examining Ricketts’ use of Christianity as a literary tool in “A Glimpse of Heaven,” and put forth the argument that his goal with this work was to portray art and literature as concepts that, while able to be manipulated and engaged with by humans, are ultimately beyond our control and understanding, much like the Christian God.

“A Glimpse of Heaven” is a short story centered around a young girl who spends her last day alive wandering the streets of London, caring for her younger siblings, and providing for her family in place of her grief-stricken father, who spend most of his day at the pub. The story begins with a bleak portrayal of London’s streets on a rainy evening, describing the scene as “dismal” (Ricketts 19) and creating atmosphere through personification of the objects that are experiencing the bad weather. Phrases such as “…the wind moaned, and the river sobbed, with weariness” (Ricketts 19) further illustrate this point. He also writes of the lanterns as winking at one another and thinking of themselves as shining like stars. We are then introduced to the protagonist of the story, the eldest daughter of a family of four still grieving and recovering from the loss of their mother. When we are introduced to the protagonist, we see her pondering the likelihood of her being able to bring her father home from the public-house without having to give him any more money for alcohol, as he had already spent a great deal of both money and time at the bar since the death of his wife. Deciding there was no other way, our main character starts towards her home to wait for her father and check on her younger siblings.

As she makes her way home, our protagonist comes across a deli and peers through the window to see many nice things such as “shining hams, crimson sausages, jellies…golden pies, all trimmed with paper roses” (Ricketts 20). While seeing these beautiful sights that contrast the bleakness outside the window, the main character begins to imagine herself taking some of the food home and brining a paper rose along with her to leave on her mother’s portrait. She imagines that, when she brings the food home, her family is ecstatic and laughing, including her father, and she thinks to herself, “How bright it would look!” (Ricketts 20) to be in such a life instead of her dark and damp reality. She makes her way inside the shop but two ladies come in before she can order from the shopkeeper. One of the ladies offers the main character a mince pie stating that, “That little girl ain’t overfed” (Ricketts 20) and “I don’t like to see children starving” (Ricketts 20).

After leaving the shop, the protagonist notes that her father was still at the bar even though it was getting so late and begins walking home. When she arrives at her house, she finds her younger sisters sleeping in a room that “…seemed damper and colder than outside” (Ricketts 21). The protagonist decides to sleep as well but is soon woken up by rays of sunlight bursting into the room. When she gets out of bed, she notices the stained wall-paper changing into beautiful artworks of nature and is suddenly wrapped up by magenta roses that sprung from the walls. Just as she is enjoying her dream, an angel appears before her and tells her that she must come to heaven. On the way to heaven, the girl is reluctant to leave her family because she is concerned about what they will do without her there to help. She asks God to let her go back for a moment but he smiles at her while turning her into a blue lily and adds her to his throne of flowers while each petal on the throne whispers, “Peace! peace! peace!” (Ricketts 22).

His Life, His Love, His Legacy

Born in 1866 Geneva, Switzerland, Charles De Sousy Ricketts spent his early years living with his painter father and musician mother in various European cities, such as London, Lausanne, and Amiens. This frequent exposure to art inevitably influenced Ricketts’ artistic tastes to the point that he would choose to pursue an artistic career for his future, like his parents. After the death of his mother, Ricketts moved to London with his father and sister but spent most of his time there being self-educated because of his lack of proficiency in English. A great deal of this self-education was spent indulging in various literary works and studying artworks at museums, thus furthering his passion for art and literature and shaping his understanding of art as a broad concept to be less in-line with conventional understandings of art at the time. Eventually, Ricketts enrolled at London’s City and Guilds Technical Art School where he spent his time shadowing wood-engraver Charles Roberts.

While attending the City and Guilds Technical Art School, Ricketts would eventually meet painter Charles Haslewood Shannon and the two would go on to form a close and lasting relationship both professionally and personally. The two were said to have been so similar in mind to the point that no decision was ever made based one party’s individual preferences; rather, each decision was made collectively and every thought was wordlessly share between the two. After concluding their studies London, Ricketts and Shannon set off for Paris to establish their artistic careers as a number of artists and writers had done before but eventually took over The Vale Press where they would publish their first magazine The Dial. A five issue magazine, this work was dedicated to the creation of art in every sense of the word and this dedication can be seen in the labor intensive work that went into Ricketts’ creation of the woodcut illustrations used throughout the magazine.

Outside of his woodcutting illustrations, Ricketts also worked on paintings, sculptures, and writing as his career and skill in the arts developed. As an artist and writer, Ricketts was influenced by ideas of the Aesthetic Movement and renaissance art, and would use these ideas in his artistic and literary works to make large assertations on the state of art and literature in society to encourage discussion on how people ought to engage with art as a whole. Despite being a non-believer in the Christian God, Ricketts would often find inspiration in Christian ideologies and figures like Jesus Christ. In his biography on Charles Ricketts, J. G. P. Delaney writes that Ricketts would use prominent figures like Christ and Cleopatra in his work because he was inspired by their courageous behaviour at the time of their death.

Using God

In “A Glimpse of Heaven,” Ricketts uses Christian symbolism and metaphor to draw parallels between a life lived without art and one lived with, as well as to make a statement about the existence of art. Through his technique, Ricketts has the audience consider why we create art, why we indulge in it, and why we can never fully control or understand it. An example of this symbolism can be found in the scene wherein the main character is approached, in her dream, by an angel. The angel, described as being “brilliant as a rocket” (Ricketts 21), tells the protagonist that she must come to heaven immediately and, despite her protests, she finds herself on top heaven’s clouds. In this scene, the angel is meant to represent art’s compelling and forceful nature; its ability to show us beautiful sceneries and give take us on unforgettable journeys, sometimes without us even being aware of what is happening. Ricketts’ angel visualizes an artistic adventure as it takes the protagonist through pink and purple morning clouds and “sheets of gold” (Ricketts 21) to remind society of the importance and magic of these experiences in a time when the industrialization of art is being pushed.

Ricketts’ use of Christian symbolism in this work can be seen in his depiction of the Christian God. Ricketts uses God to show art’s influence over human nature and how it can shape us into any form it desires. At the end of the story, the main character pleads with God to allow her a few more moments of life to take care of what remains of her family. She expresses concern over her father’s emotional state and the physical and emotional wellbeing of her younger siblings, stating that her father is in no condition to take care of the children and that they will likely go hungry without her around. The main character is turned into a blue lily, “the colour of mercy” (Ricketts 22), before she can finish her request, and is added to God’s throne of flowers. In this scene, the blue of the lily symbolizes God’s mercy towards the girl after her suffering on Earth, while the flower itself represents a number of things. Lilies in Christian media often represent the suffering and sacrifice of Christ but can also represent purity. Here, Ricketts uses both these meanings of the lily to portray the main character as a Christ-like figure and show how the reward for her suffering is to be granted mercy at the end of her life. Ricketts also uses God in this scene to parallel the existence of art. He argues that art, much like his depiction of God in this scene, transforms us and shapes us unwillingly, and that what we receive from art is dictated by our character.

As a follower of the Aesthetic Movement, Ricketts argues his point in this way to show the parallels between humanity’s relationship with art and with the Christian God and to show how art, much like depictions of the Christian God, should be feared and respected because of its ability to shape humanity while existing beyond it. In Ricketts’ mind, art is not something that an individual creates; it is something that creates an individual and saves them from the suffering of life.

On Being Contrarian

At the time of this story’s publication, there was much debate over the meaning of art and how it ought to exist and being engaged with by society. Many artists would associate themselves, either loosely or strongly, with a number of artistic movements like the Arts and Crafts Movement or the Aesthetic Movement/Aestheticism. Because each group had conflicting opinions on the topic of art’s existence, and every artist in those groups a dozen more, there was an emergence of indirect conflict in the creative works of writers and artists alike. Artists had eventually devoted their works to the upholding of their beliefs on art, or to the defamation of another’s. Like Ricketts, many artists and writers would make use of Christian symbolism to argue these points. The way in which this symbolism was used cannot be said to have been entirely binary, however.

When we examine the use of Christian symbolism for the purpose of explaining art’s purpose, we see that it falls on more of a spectrum on which a number of ideas are represented. Many artists would outright disagree with Ricketts’ position, and their work would reflect this. This spectrum becomes more clear in the case of writers like Laurence Housman, who would agree with Ricketts’ notion that art exists beyond human influence and understanding and that our experiences with art shape our character whether we consent to it or not. Artists like Housman would disagree, though, with the idea that art is a salvation. In his work “Open the Door, Posy!”, Housman argues that, despite the fact that art exists beyond human control, and its ability to influence one’s character, it cannot save us from the inevitable torment of death. In any case, whether we are able to find a satisfactory answer or not, there is strong merit in engaging with literary works like these that strive to achieve some sort of understanding of art’s role in our lives.

Works Cited

Cook, Matt. “Domestic Passions: Unpacking the Homes of Charles Shannon and Charles

Ricketts.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 51, no. 3, 2012, pp. 618–640.,

doi:10.1086/665270.

Delaney, J. G. Charles Ricketts: A Biography. Clarendon Press, 1990.

Housman, Laurence. “Open the Door, Posy!” The Dial, vol. 5, 1897, pp. 4-7. Dial Digital Edition, edited by Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2019-2020. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020. https://1890s.ca/dialv5-housman-posy/

Christianity and Literature, vol. 29, no. 3, Sage Publications, Ltd., 1980, pp. 25–70,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/44310704.

Ricketts, Charles S., and Nicholas Frankel. Charles Ricketts, Everything for Art: Selected Writings. The Rivendale Press, 2014.

2, Modern Humanities Research Association, 2006, pp. 245–58,

https://doi.org/10.2307/20479255.22