Gaelic Revivalism and Colonialism in Fiona Macleod’s “Morag of the Glen”

©Morgan Howey, Ryerson University 2018

Introduction

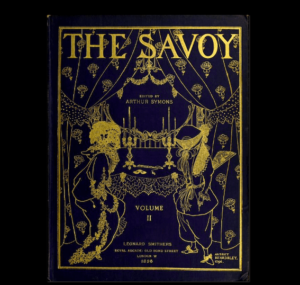

Fiona Macleod’s “Morag of the Glen” in Volume 7 of The Savoy is representative of the Gaelic Revival while conversing with notions of colonialism and the colonial binary. Through Macleod’s use of Gaelic words and songs what can be seen as a folktale lacking in a moral compass instead participates in a resurrection of old memories and stories that contain deep moral codes which at once is representative and in conversation with the national identity — or lack thereof — of Irish peoples, displaced or not.

Fiona Macleod may not be the name associated with the Irish Revival today, as it was in the 1890’s, but that is due to the fact that Fiona Macleod was the pseudonym William Sharp used to write under —especially in regards to Irish and Gaelic literature. Throughout the little magazines of the fin-de-siecle various stories, poems, and writing can be found written by William Sharp and Fiona Macleod — some even in the same volumes of periodicals — and yet the two authors are seemingly different in style and content. William Sharp which was the intellectual and conventional side, and Fiona Macleod was his “second self” that developed from his childhood and Sharp’s obsession with nature, Celtic romanticism, and his connection to ancient wisdom, and his “worship of beauty” as described in William Sharp (Fiona Macleod) A Memoir (Sharp E. 223).

Macleod’s “Morag of the Glen”, written under Sharp’s pseudonym Fiona Macleod as opposed to Sharp himself, is exemplary of Irish folklore writing as it deals with mysticism in the form of strange happenings that seem connected or related to either the Gaelic Bible the Campbells read from, or metaphorically through the weather and the water that runs through Strathglas. The folklore also reiterates a few moral lessons, and these lessons touch on colonialism through there representative figures as seen in the colonized Gorromalt, Elspeth, Morag, and Meireall (to name a few) and the colonizer Jasper Morgan, and Lord Greyshott the Englishman.

“Morag of the Glen” as Gaelic Revivalist Literature

The foremost question that was imposed on Macleod’s work was the authenticity of it. While I could not find a Morag character in my research that existed in other mythologies or Celtic folklore, the inherit oral nature of Celtic and Irish stories and culture must be factored in. In some cases these stories may be passed through Macleod and simply not previously recorded, or alternatively they could be manifestations or reincarnations of other characters or stories. Taking this into account, and the lack of Irish literature recorded in print form at the time, Macleod was also in a position to re-create national identity through her writing. Using print and the English language Macleod is also conversing in the “language of power”; by using English “Morag of the Glen” produces in the colonizers domain. Further, because Macleod uses Gaelic words and songs in “Morag of the Glen” it can be suggested that in doing so the colonized Gaelic language is given a platform and converses with colonial written text. As opposed to judging the cultural authenticity of a folklore, Castle suggests viewing these new interpretations and representations as cultural performances, significant in their own being. In “Irish Revivalism: Critical Trends and New Directions” Castle further posits that

in an imaginative interpretation, the revivalist may use critically or tactically the tropes of legend, even of the primeval and of all that defies the Truth of history, to undermine the strategic (i.e., institutional) legitimacy of colonialist misrepresentations. (Castle)

This gives agency to authors and other Irish identifying revivalists that aim to correct preconceived or colonial ideas of Irish nationhood and identity. Bryan further refers to the late oral traditions of Celts as necessary only in that they gave way to “a larger imaginative world [other] than the material world of English colonization” (74). This would allow for the removal of self from a colonized place, even if only briefly in a story such as “Morag of the Glen”, in which the reader is transported to Strathglas. Although, even there, colonialism and the “Londoner” encroaches on the dwellers who have lived off the land for generations.

The Colonial Binary

Drawing from Amanda Bryan’s “Decolonization and Mysticism in William Butler Yeats’s The Celtic Twilight and The Secret Rose” multiple forms of the colonial binary —the colonial binary being the colonizer and the colonized— can be found in Macleod’s “Morag of the Glen”. Representation of the colonial binary can be seen, respectively, in the colonizing “Londoner” and those forcing the Campbell’s from their ancient land, and the colonized being the Campbells who are forced into the structures of English society by the procurement of their land. The colonizer forces the Campbell family to assimilate into their code of conduct. While Archibald Campbell is first recognized for his brutish anger and quick temper, his transformation throughout “Morag of the Glen” can be interpreted as a shifting in perspective and moral code as he ends the story by agreeing to go see Muireall, who he had previously condemned.

Morag, and to some extent Gorromalt, seems to posses a type of primitiveness Gregory Castle describes in Modernism and the Celtic Revival. This primal nature in the eyes of the colonizer is seen as savage and uncultured. For the colonized, in this case the Celtic, these primitive qualities are admirable and signify a connection to something ancient and knowledgable. This definition does not deny the primitiveness of the Celtic, but makes it valuable and connected to something timeless (Castle 51). In this way Macleod uses Morag as a representation of connection to ancient wisdom that demonstrated Macleod’s spiritual need to connect to beauty in a way that older Celtic poets had by comparing Morag to fawns, and aligning nature with aspects of her features like the sunlight in her hair (Welshman 68). By transcending the binary view of primitiveness equating to something negative, Macleod converses with the larger context of recreating not only attitudes but the national identity of Irish people, and realigning these notions so that the primal nature long associated with Celtic culture would be seen as good attributes.

Gorromalt is primitive in his quick temper and brutishness, he is also the only character that has direct contact with a mystical element when something seemingly brushes against him, when in fact there is no one there (Macleod 30). He is also the character that under goes the most change in that by the end of the story he finds peace after reading from the Gaelic Bible after seeing the riderless horse and watching Rory, the families blind dog, go into a fit of madness. Gorromalt also choses to see Muireall after the sorrow of sorrows, despite her deceit and betrayal to the family. This mercy that Gorromalt extends towards his kin can be taken as a moral lesson in which regardless of Muireall’s defiances, family loyalty is paramount. In this way Gorromalt is a colonized in transition. From feeling angry and rejecting his identity by calling his wife Elspeth foolish for turning to the Gaelic Bible and singing charms, he ends by turning to the bible in search of inner peace, and finds such peace.

Another colonial binary can be seen within William Sharp’s use of a pseudonym for his second self. The William Sharp that presents himself as such, is the masculine representation of the colonizer, the intellectual who is conventional, and studied, who does not dive into the personal or the idealization of Celtology or feelings. Fiona Macleod however, is the barbaric feminine colonized, more in tune with nature and all things living, more wild and connected to her feelings, and able to be transported to places where reason is not as set in stone. Through this mode Sharp was able to use the feminine voice and distance of Macleod to converse with ideas and feelings that he felt he couldn’t publish as William Sharp. This also speaks to the authenticity of writing such as “Morag of the Glen”. While according to Julian Hanna, many writers of the 1890’s disliked Sharp’s writing and associated him with London; with Macleod, a distinct voice came through that was associated with Scotland and Celtic culture (Hanna). Macleod as a made up name was taken to have more value authentically than Sharp himself, and was thus received better by other Revivalist writers and consumers.

Feminine Sorrow

The first thing we are introduced to in “Morag of the Glen” is the notion of a “sorrow of sorrows… [a]nd when a woman has this sorrow, it saves or mars her” (Macleod 13). This sorrow of sorrows is what eventually mars Muireall and leads to her suicide by poison. Bryan argues that “Irish feminine beauty was often associated with sorrow… [that] beauty in a colonized place links with anguish because for the colonized no other option but anguish exists” and because of the colonial binary in which the colonized — the Irish people — were repeatedly pegged as brutish and uncivilized and all together lesser in comparison to the English, it can determined that they too experienced this anguish (Bryan 74). In a sense “Morag of the Glen” seems to align with this notion of feminine sorrow in Muireall’s death, and in Aunt Elspeth who has to live with and be married to Gorromalt. Elspeth must weather the violence of oppression through colonialism and through her own further oppression in her marriage. In another case it uses this sorrow and retaliates with the death of Jasper Morgan (the Englishman that impregnated Muireall and brought her this sorrow of sorrows and the wrath of Archibald Campbell) induced by Morag as the representation of Gaelic strength and culture. Morag who possessed a “hillside wildness” and whose name held significance in old family stories and Gaelic songs sung by the milkmaids is the ultimate representation of the colonized, or of Macleod’s version of the colonized. Morag is in tune with nature and the old ways, “held a living light”, and who “saw the soul if it” and ultimately takes the meaning of the old Gaelic ballad sung by the maids and forces Jasper Morgan to commit suicide (Macleod 14-17). On the other end of the spectrum is Gorromalt, who is the colonizers interpretation of the colonized; someone brutish and savage, and succumbing to assimilation. Gorromalt’s only redemption is in forgiving Muireall of her betrayal. “Morag of the Glen”, while not entirely morally correct as it includes suicide as a final conclusion, contains what Bryan calls deep moral codes. Morals guiding characters beyond the most obvious exercise of right and wrong, which gives the Celtic identity a sort of past and code as it converses with notions of colonization.

Conclusion

“Morag of the Glen” is a recounting and retelling of folk-tradition. First the song “Morag of the Glen” is heard by Morag and the narrator in which Morag kills a man, then the Morag of the Campbells kills Jasper Morgan. The context shifts. Morag Campbell in the context of a colonized landscape murders by suggestion the epitome of the colonial. The “Londoner” Englishman uproots family and tradition, and impregnates and steals the virtue of the colonial. Macleod justifies Morag’s murder, and thus this Gaelic identity. Macleod’s depiction of a Gaelic family tied to its ancient land is not a retrieval of lost Celtic culture, but rather a representation meant to open up the future world of spirituality and Irish identity. While this story can be divided into good and evil, the lines are blurred as the primitive is purposely painted in a new light — one connected to nature, feminine beauty, and ancient wisdom, and the decolonization of the primitive is meant to create and justify nationality, thus creating a sense of national identity for those whose colonized culture was once painted as savage and other. The use of folktale not only historically and culturally represents and is capable of being representative of Celtic/Irish/Gaelic culture, but also offers a modality in which these mystical connections to nature and feminine beauty are easily accepted and interpreted. Gregory Castle’s “Irish Revivalism: Critical Trends and New Directions” sums up the Revivalist aim by stating…

Revivalism does not seek to recover the past, though it uses all the modalities of memory and remembrance… Its basic principle is to give or make life again, to give life anew to language and texts – not simply a repetition or return… but a rectification and overcoming of misprision. Revivalism is a dynamic, often contradictory process, newly original, in which poetry and drama, history and legend, oration and essay, folktale and song are all regarded as beautiful, productive errors.

Works Cited

Bryan, Amanda L. “Decolonization and Mysticism in William Butler Yeats’s The Celtic Twilight and The Secret Rose.” Irish Study Review, vol. 23, no.1, 2015, pp.68-89.

Castle, Gregory. “Irish Revivalism: Celtic Trends and New Directions.” Literature Compass. Blackwell Publishing. 2011.

Castle, Gregory. Moderism and the Celtic Revival. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Hanna, Julian. “Manifestos at Dawn: Nation, City, and Self in Patrick Geddes and William Sharp’s Evergreen.” International Journal of Scottish Literature, vol. 8, 2011.

Macleod, Fiona. “Morag of the Glen.” The Savoy, vol. 7, 1896, pp.13-34.

Sharp, Elizabeth A. William Sharp (Fiona Macleod) A Memoir. Duffield and Company. 1910. Open Library.

Welshman, Rebecca. “Dreams of Celtic Kings.” Mysticism, Myth, and Celtic Identity, edited by Marion Gibson, Shelley Trower, Garry Tregidga, Routledge, 2013, pp. 60-69.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and provided solely for the purpose of research, private study, or education.