The Yellow Book’s Decorative Women: Critiquing the Victorian Aesthetic Ideal

© 2020 Sabrina Pavelic, Ryerson University.

An Introduction

The Victorian ideal and the New Woman seem, at first, to be dichotomies of one another. The two, however, cannot be so starkly opposed. This is not because the ideal Victorian woman is, in some inconspicuous way, actually a New Woman. She is not. We will discover as much as we explore a series of images and a central text in the Yellow Book. Short-story fiction writer, co-editor of the Yellow Book, and New Woman herself, Ella D’Arcy, created women in “At Twickenham,” who cannot be so boldly dichotomized. The sisters, Minnie Corbett and Loetita Wray, are painfully portrayed as existing inside their home so passively as to become the decoration that surrounds them. The woman as décor motif, then, is crucial to unpack. I argue that the decorative women and decorative tropes that appear in each image and text, in fact, critique the aesthetic ideal of the Victorian woman.

Alongside Ella D’Arcy’s “At Twickenham” in Volume 12, I will also unpack Gertrude D. Hammond’s illustration titled “The Yellow Book,” which appears in Volume 6. My focus on the aesthetics of the Victorian ideal as a critique forces a consideration of the Yellow Book’s own art editor: Aubrey Beardsley. The infamous Beardsley not only edited artwork for the Yellow Book until 1895 but also contributed much of his own talent. As such, we will examine Aubrey Beardsley’s women in illustrations such as the woman on the Prospectus to Volume 1, “Night Piece” (Volume 1), “The Slippers of Cinderella” (Volume 2), “La Dame aux Camélias” (Volume 3), and “The Mysterious Rose Garden” (Volume 4). As we will see, the concept of the male gaze or male perspective follows throughout each image and text. As such, we also embrace and incorporate this perspective rather than rejecting it.

Methodology

Methodology

As we navigate through these images and text, we must take into consideration the very medium in which it appears. The Yellow Book is the epitome of the “British avant-garde journals” in the Fin de Siècle (Claes 1). As such, it was particularly concerned with “an integration of medium and message, form and content, ethics and aesthetics, that would be necessary to produce what has come to be known as the ‘Total Work of Art’” (Claes 1). We know that the Yellow Book considers itself in this vein of ‘Total Work of Art’ because its inaugural volume makes an explicit statement in separating Letterpress from Picture (later Literature from Art). The Yellow Book’s “fullest expression to the double resistance of graphic artists against literature, and Art against commerce” was symbolized in these words on the contents page (Dowling 118).

From its very conception, the Yellow Book situated itself as ambitious, but overall, it was representative of something new: the avant-garde. Indeed, it was arguably “commercially the most ambitious and typographically the most important of the 1890s periodicals” (Dowling 117-118). As we move to dissect the contents of the Yellow Book and its decorative women, we must keep in mind this little magazine’s dedication to existing as a ‘Total Work of Art.’ It also speaks to Walter Pater’s wisdom on “poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for its own sake…. For art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake” (Pater 2-3). Consider both the text and images of the Yellow Book as art for art’s sake.

Additionally, Agnieszka Setecka’s article “Needles, China Cups, Books, and the Construction of the Victorian Feminine Ideal in Rhoda Broughton’s Not wisely, but too well and Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South,” provides a foundation for understanding the connection between objects and women. Setecka outlines objects as becoming “a site where the material and immaterial meet, where the borders between the economic and the domestic world blur” (Setecka 49). I, too, assert that objects provide a transcendental site for the blurring of the economic and domestic world. However, I do so in asserting that women portrayed as stereotypically passive, quiet, and dependent, only furthers their portrayal into the realm of the aesthetic Victorian ideal. It is this depiction of an aesthetic Victorian ideal that, in turn, acts as a critique of itself.

What is the Victorian Aesthetic Ideal?

What is the Victorian Aesthetic Ideal?

I would like to consider the Victorian aesthetic ideal under the same lens as Sarah E. Maier. She outlines it as one where women are “[u]nfortunately… constantly judged according to their ability to live up to or to project the ideal image which men desire” (Maier 36). What is interesting in Maier’s interpretation is her emphasis on image, appearance, or aesthetics. This is one which I also emphasize. Additionally, she considers the image that is projected onto women by men or the male desire. This is also key to my argument. As we work through the portrayal of women by women in Ella D’Arcy’s “At Twickenham” and Gertrude D. Hammond’s “The Yellow Book,” we also notice hints of the male perspective.

These hints become overt as we outline Aubrey Beardsley’s women. The integration of the male perspective through each text and image is one that shapes my argument. If the male gaze shapes the ideal, then is his depiction of the ideal a critique or a desire? I find that male desire does influence an overall understanding, especially in “At Twickenham.” As such, male desire is often not in line with the aesthetic Victorian ideal. Indeed, the two cause friction, friction that ultimately shapes the critique of this ideal.

Before we move into discussions on each piece, I would like to keep in mind gender distinction in the periodical itself. Margaret Beetham connects “femininity” as that which “was always located in and defined by appearance, as masculinity was not, [and so] the stress on the visual character of the periodical was a further ‘feminisation’” (Beetham 121). The very nature of the periodical as particularly concerned with being a ‘Total Work of Art,’ placed it within the realm of feminisation. This feminisation of “New Journalism” thus connects it to the New Woman (Beetham 111). And so, we must remember that each moment inside the Yellow Book is but a part of a greater whole.

![]()

“At Twickenham” by Ella D’Arcy, Volume 12

The short story “At Twickenham” by Ella D’Arcy explores a seemingly mundane plotline wherein the character of Loetitia finds a fiancé in Dr. Jim Matheson. Matheson ends the engagement before they marry, and Minnie’s husband, John Corbett, confronts Matheson. Corbett effectively leaves Matheson having apparently affirmed that Matheson is nonetheless the “cleverest, the most entertaining, the most lovable of men” (D’Arcy 331). In such a seemingly familiar tale of love and courtship, D’Arcy twists the predictable outcome. This atypical conclusion helps us understand the characterization of the women (Minnie and Loetitia) as critiques rather than perpetuations of the Victorian aesthetic ideal.

Firstly, the characters live in “a villa that rejoiced in the name of ‘Braemar’” (D’Arcy 313). The fact that their villa is named effectively personifies it. The inanimate building becomes a character itself, to be dressed and tended to. Further, the home is almost excessively described. It is

a villa that flared up into pinnacles, blushed with red-brick, and mourned behind sad-tinted glass. The Elizabethan casements let in piercing draughts, the Brummagen brass door-handles came off…, the tiled hearths successfully conducted all the heat up the chimneys… (D’Arcy 313-314).

The descriptions also tend toward feminisation. For instance, the villa “blushed,” and “mourned,” which are emotional qualities that are often associated with women. The characterization of the villa also continues into the characterizations of the women. This characterization of the women alongside the house itself is what helps us distinguish the women as depicted so passively as to become a part of the home: women as mere domestic decoration. Minnie is arguably the most passive of the two. She has accomplished the only important task in a Victorian woman’s life: marriage. As such, she no longer has any active thoughts. She cannot even seem to “teach her family to remember to call her [Rita],” the name she prefers (D’Arcy 314). First, we see Loetitia introduced to us through her dressing “of ‘Braemar,’ with frilled Madras muslin, drap[ing] the mantel-pieces with plush, [hanging] the walls with coloured photographs, Chinese crockery, and Japanese fans” (D’Arcy 314). This description is the first we receive of Letty. It is undeniably attached to that of the home, insinuating an inherent connection between the character and the decoration to which she tends.

Minnie is also implicated in this decorative trend. Both sisters “made expeditions into town in search of pampas grass and bulrushes, with which in summer-time they decorated the fireplace, and in winter the painted drain-pipes which stood in the corners of the room” (D’Arcy 314). The women’s activity here is exclusively to deal with decoration and the home. There is an inherent connection in such insistence on the decoration and the women. Both the personification of the house and the painful passivity of the characters work together to situate them almost on the same level of activity. After all, “[t]he sisters suffered terribly from dulness, and one memorable Sunday evening… they took first-class tickets to Waterloo, returning by the next train, merely to pass the time” (D’Arcy 314). These two characters are described so uselessly to the point of exaggeration. It is difficult to believe that they actually take a first-class train ride to Waterloo “merely to pass the time.” And, further, it is this minimal and utterly useless activity that makes their evening “memorable.”

To a modern readership, this depiction appears overtly passive and exaggeratedly pathetic. While it is exaggerated, it is also exaggerated from the quintessential Victorian ideal. D’Arcy does so to highlight the image or the aesthetics of the ideal Victorian woman. Sarah E. Maier recognizes that Ella D’Arcy often exaggerates these stereotypical tropes in her characters, but this is to show how they, indeed, subvert cultural ideals. For instance, the character of Nettie in “A Marriage” exhibits power from “her ability to subvert the perceived ideal” (Maier 41). However, she only appears “to represent the domestic ideal” (Maier 42). Instead, she uses her perception to manipulate the situation. This is similar to what happens in “At Twickenham,” except that the characters do not use this perception for manipulative purposes. Instead, it is the perception itself that becomes critiqued in Dr. Matheson’s reaction to it.

If the ideal is shaped by the male desire, then Matheson’s desire goes in complete opposition to the conventionally accepted ideal: one the two sisters embody. When Matheson explains his rejection of Loetitia, he states that it is because “she’s too good, too normal, too well-regulated. [He] could almost prefer a woman who had the capacity, at least, for being bad! It would denote some warmth, some passion, some soul” (D’Arcy 331). It is, therefore, in this crucial confessionary moment, that we discover the male ideal is not in line with the Victorian ideal. And, further, it is this affirmation that men do not want what women have been taught to do that allows us to understand the critique as it plays out in this short story. In fact, this objectification of Minnie and Loetitia in their state as women of decoration completely reverses itself when both Matheson and Corbett agree on Matheson’s leaving Loetitia. The aesthetic ideal is not the ideal because it is not upheld by the men in the story. That is not to say that this is a cultural truth. It is merely how D’Arcy is able to portray her point: through the use of these male characters and their support of, and desire for, “bad” women.

![]()

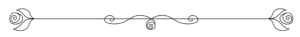

“The Yellow Book” by Gertrude D. Hammond, Volume 6

Hammond’s commissioned artwork for Volume 6 of the Yellow Book (see fig. 5) was itself titled “The Yellow Book.” This illustration shows a young woman looking down on a copy of the Yellow Book. The man in the image is showing her its contents, and she looks seemingly uninterested. The woman’s face appears notably blush. The room in which the man and woman appear is also crucial. We assume the two are upper-middle-class due to the man’s suit attire and the woman’s dress. The drawing-room in which the image is captured is also particularly decorated with “japonaiserie” (Stetz and Lasner 29). The man appears quite engaged and animated in showing the woman what is inside this copy of the Yellow Book. The woman, however, appears disdainful, quiet, and rather passive. Even though we can see that the woman becomes part of her own décor as a minimal, subdued, and passive presence, there is more to the image than this. Margaret D. Stetz and Mark Samuels Lasner state that “the two upper-middle-class figures… were evidently in conflict over the magazine’s propriety” (Stetz and Lasner 29). What both the décor and the woman’s disdain suggests is that “even those who might consider the magazine daring would still find it fit to be placed in the most tasteful, distinguished houses” (Stetz and Lasner 29). This suggestion speaks to both the marketing and perception of the magazine. Indeed, the image was used on behalf of the editors to produce a guided response from the public towards the Yellow Book (Stetz and Lasner 29).

Let us return to the apparent passivity, or rather, the disdain in the woman. She is effectively likened to her surrounding decorations as she leans on the couch. She also looks reluctantly to the Yellow Book, while her male counterpart expresses clear enigmatic vibrancy and activity. He is engaged, and active, while she appears to represent the very opposite. The fact that her indifference is directed towards the Yellow Book in the image is significant. It points to an awareness that must not be overlooked. She can dislike the avant-garde periodical if she so chooses (as would the ideal Victorian woman), but she nonetheless may feel comfortable placing it amongst the items in her home. As such, the image acts as both a critique and perpetuation of the Yellow Book itself and so, too, does it critique the trope it seems to perpetuate: the passive or decorative aesthetic of the Victorian ideal.

![]()

Aubrey Beardsley’s Women, Volumes 1-4

Let us turn to a select few works of Aubrey Beardsley’s from his time as art editor of the Yellow Book. As we do, we must keep in mind Beardsley’s own inclinations. For instance, Arthur Symons notes that

One of his poses, as people say, one of those things, that is, in which he was most sincere, was his care in outwardly conforming to the conventions which make for elegance and restraint; his necessity of dressing well, of showing no sign of the professional artist (Symons 27).

This tendency toward outward conformity is particularly interesting. In his life, Beardsley clearly enjoyed the ability to blend into conventional society, yet his art remains so highly ambitious and avant-garde. It is clear this same tendency flows into his artwork: a propensity for the conventionally subversive.

The Woman on the Prospectus to Volume 1 and “Night Piece,” Volume 1

Both of the women in these pieces are depicted alone at night. The woman on the Prospectus is searching through stacks of books, while a grotesque salesman looks disdainfully at her (see fig. 6). The decorative nature of these pieces lies in each woman’s clothing. They are, for the most part, shrouded in darkness. Beardsley utilizes blank space here to emphasize their being out at night. We also notice the similarities in their hats. They are grand pieces, likely with feathers atop both their heads. This playfulness with outward conformity in their garments and clear unconventional actions in their being out at night highlights the critique errant in Beardsley’s work. The women are dressed in upper-middle-class garments, which in itself alludes to the decorations prevalent in the Victorian home. If we look closely at “Night Piece,” (see fig. 7) you may notice that the woman’s neckline appears provocatively low. At first glance, that is. If we look closely we can see a bow tied to her neck. This may be a necklace of sorts, but it also implies a neckline. The garment could switch from dark black to white, and this high collar is the only piece of the garment in white. The illusion comes because the woman’s skin also remains white, and so we assume that the neckline must be this low. However, this is not so easily the case. As such, the women Beardsley portrays here are indicative of the woman-as-decoration motif because their garments are so illustrative of the decoration inside Victorian homes. In this sense, they are also indicative of the Victorian aesthetic ideal. However, as we know Beardsley to be, it is not so simple. The critique lies in his portrayal of them as New Women: that New Women dress and appear just as conventionally as the ideal Victorian woman does.

“The Slippers of Cinderella,” Volume 2

This illustration (see fig. 8) follows in suit with our previous two: a woman outside alone. However, it differs more dramatically in her depiction wearing a short dress. Her heels and, indeed, part of her legs are showing. The title even forces the eye downward to her legs, effectively emphasizing the bareness of them. This woman is also adorned with a feather, a rather large one, atop her head. And, further, she wears an apron-like garment above her dress. These objects allude to the domestic sphere and bring her garments back to the decorative motif. The feather, especially, implies decoration. There is no clear use for this feather other than to augment the outfit itself, such is the nature of decoration. The darkness, here, also reminds us of the previous two images. This woman, Cinderella we assume, is also alone at night.

The use of a fairytale character in his title is also significant. Remember that fairytale stories must be found inside the pages of a book. Agnieszka Setecka posits that

Books… are the most ambiguous… signifiers of genteel feminine virtues…. Although… they are associated, at least to some extent, with women and to construct the ideal of (middle-class) femininity they, nevertheless, traditionally belong to the male domain of learning (Setecka 58).

Beardsley takes this contentious trope even further by alluding to a fairytale. Fairytales are often associated with children, and children, by extension, with their mothers. As such, Beardsley’s allusion to fairytale books in his “The Slippers of Cinderella” help critique the woman-as-decoration motif. It does so because of Setecka’s assertion that books are both “signifiers of genteel feminine virtues” as well as belonging to the “male domain of learning.” These seemingly opposing forces can be applied to the artwork, too. The mixture of the avant-garde and New Woman clashes with allusions to the Victorian aesthetic ideal in “Cinderella”’s garments.

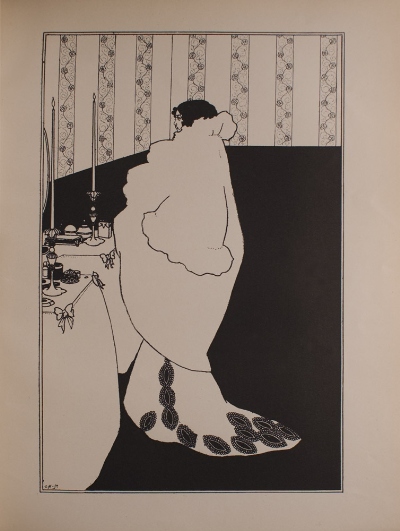

“La Dame aux Camélias,” Volume 3

The French title of this illustration, “La Dame aux Camélias,” directly translates to The Lady of the Camellias. A camellia is, of course, a type of flower. This is significant because the woman in the illustration (see fig. 9) is enveloped in a coat reminiscent of a camellia flower. She is literally engulfed by it. Unlike the other artworks, this woman is located indoors. She is standing in front of a richly decorated table, with candles and (presumably) plenty of food. The rest of the room appears bare as the floor remains completely coloured in black. The perspective is stretched so that we assume the corner of the room is where the wallpaper begins. The wallpaper shows a zig-zag pattern, reminiscent of flowers. Perhaps, even, the camellia flower.

This illustration is interesting because the woman appears enveloped by her wardrobe. As we have seen in previous images, the woman’s wardrobe mostly alluded back to the domestic sphere and decoration. This time, we can only see the embellishment of her gown at the bottom. Instead, the coat is the primary focus and it is the coat that takes us outside of the domestic sphere. Because the coat alludes to the camellia flower in its collar and sleeve, we are taken outside of this domestic sphere. The woman, though she passively stands in front of the beautifully adorned and decorated table, is thus taken outside as well. She appears weighed down by her coat. The need for the woman to step outside of her intended sphere is all-consuming. Even though she is ideally depicted (there is no scandal in her garments and there is, too, no scandal in being indoors), Beardsley nonetheless critiques this idealistic and conventional outward appearance. All that he does brings us back to the fact that appearance is not sufficient for meaning. As, too, does the depiction of the woman as decorative. It does not suffice for our understanding. Indeed, the image becomes a critique of this Victorian aesthetic ideal.

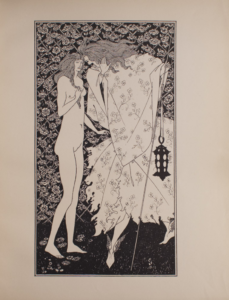

“The Mysterious Rose Garden,” Volume 4

This illustration (see fig. 10) appears in the final volume of Beardsley’s run as art editor at the Yellow Book. The insinuation of the garden and the depiction of an androgynous being whispering in the ear of a woman is a clear implication of the original sin in the Garden of Eden.

Firstly, let us look at the background. Although this is meant to be a garden, and, indeed, we do see roses behind them, the background implies wallpaper more than it does a garden. The darkness behind the lattice fence forces this interpretation. The characters appear lit up while their background does not.

The woman, or our “Eve” character, is naked. This also falls in line with the Garden of Eden implication. The human figure whispering to her could be either male or female. From the fairy-like wings on the figure’s shoes, we get the impression that this figure is meant to be neither gender. The inhuman implication also alludes back to the original sin, in which Satan tempts Eve as a serpent. Interestingly, the figure that Beardsley portrays is overwhelmed with garments. Its pattern implies the drapery that can be found in the Victorian home. The wallpaper-esque lattice fence also draws us back into the domestic sphere and the decorative trope. Even though the gender of our figure is unknown, there is a clear mixture of the decorative and domestic as well as the shocking and avant-garde.

Not only is the woman’s nude figure rather shocking to a Victorian audience, but the allusion to the original sin is also a poignant commentary. Women are deemed inferior primarily because of this original sin, and so the illustration is entrenched in gender commentary. In creating something of this sort, Aubrey Beardsley successfully portrays the conventional ideal (in the original sin allusion as well as nods to the domestic and decorative realms) but brings it once again into critique. The figure is not a representation of Satan, nor is it of a serpent. The woman clutches her chest as if shocked by the whisperings of this figure. The use of the word “mysterious” in the title, also alludes to a certain ambiguity. There can be no certainty as to what the figure says, and no certainty as to what the woman does. It is this ambiguity itself that helps critique the woman-as-decoration motif. It is one that rests in the ideal but alludes to something much more than it appears on its surface.

![]()

A Conclusion

All that we have encountered contributes to the understanding that women depicted as decoration acts as a critique of and not perpetuation of the Victorian aesthetic ideal. What we see, on its surface, is an inherently objectifying trope. Instead, it becomes a subversive critique. The lens through which we have dissected images from Hammond’s “The Yellow Book” to Aubrey Beardsley’s women, and, crucially, Ella D’Arcy’s short story “At Twickenham,” helps to hone in on this trope and its subversive practices. When we look at these nuances within the context of the late-Victorian era and within the context of the Yellow Book itself, it helps to understand how depictions of an ideal act as critiques unto themselves. While there is still more that can be done, this is nonetheless the first foray into such a perspective. We must remember that everything is not like it at first may seem.

![]()

Works Cited

An illustration from French fashion magazine Le Mode Illustrée. 1885, Getty Images, New York Post, “The beauty routine of a Victorian woman was anything but glamorous,” by Rachelle Bergstein, 23 Oct. 2016, https://nypost.com/2016/10/23/the-beauty-routine-of-a-victorian-woman-was-anything-but-glamorous/.

Ankicoleman Designs. “Tea and Books.” AliExpress, https://www.aliexpress.com/i/4000218649374.html.

Beardsley, Aubrey. “Prospectus: The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894).” Pen and ink. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library, Newark. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2011. Web. Dec. 2020. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB1_prospectus_image.html.

Beardsley, Aubrey. “Night Piece.” The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 127. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. Dec. 2020. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB1_beardsley_night.html.

Beardsley, Aubrey. “The Slippers of Cinderella.” The Yellow Book 2 (July 1894): 95. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. Dec. 2020. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB2_beardsley_cinderella.html.

Beardsley, Aubrey. “La Dame aux Camélias.” The Yellow Book 3 (Oct. 1894): 57. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. Dec. 2020. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB3_beardsley_camelias.html.

Beardsley, Aubrey. “The Mysterious Rose Garden.” The Yellow Book 4 (Jan. 1895): 270. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2011. Web. Dec. 2020. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB4_beardsley_rose_garden.html.

Beetham, Margaret. “The New Woman and the New Journalism.” A Magazine of Her Own? : Domesticity and Desire in the Woman’s Magazine, 1800-1914, Taylor & Francis Group, 1996, pp. 111-125. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ryerson/detail.action?docID=179720.

Claes, Koenraad. “Introduction.” The Late-Victorian Little Magazine, Edinburgh University Press, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/lib/ryerson/detail.action?docID=5454643.

D’Arcy, Ella. “At Twickenham” The Yellow Book 12 (January 1897): 313-332. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2013. Web. Dec. 2020. http://1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YBV12_darcy_twickenham.html.

Dowling, Linda. “Letterpress and Picture in the Literary Periodicals of the 1890s.” The Yearbook of English Studies, vol. 16, 1986, pp. 117–131. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3507769. Accessed 10 Dec. 2020.

Fenton, Roger. “Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.” 1854, Getty Images, The Guardian, “The Victorians were no prudes but women had to play by men’s rules,” by Kate Williams, May 23 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/may/23/queen-victoria-sex-nudes-paintings-prudes-women.

Hammond, Gertrude Demain. “The Yellow Book.” The Yellow Book 6 (July 1895): 119. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2011. Web. Dec 2020. http://www.1890s.ca/HTML.aspx?s=YB6_hammond_yellow.html.

Maier, Sarah E. “Subverting the Ideal: The New Woman and the Battle of the Sexes in the Short Fiction of Ella D’Arcy.” Victorian Review, vol. 20, no. 1, 1994, pp. 35-48.

Pater, Walter. “Conclusion.” The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Literature, VictorianWeb, 25 Oct. 2001, www.victorianweb.org/authors/pater/renaissance/conclusion.html.

Setecka, Agnieszka. “Needles, China Cups, Books, and the Construction of the Victorian Feminine Ideal in Rhoda Broughton’s Not wisely, but too well and Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South.” Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, vol. 47, no. 1, 2012;2011, pp. 47-60.

Stetz, Margaret D. and Mark Samuels Lasner. “Introduction.” The Yellow Book: A Centenary Exhibition, The Houghton Library, 1994, pp. 7-47.

Symons, Arthur. The Art of Aubrey Beardsley. Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/50171.

Victorian drawing-room with William Morris wallpaper and carpet. 1890, Pinterest, Dec. 2020, https://www.pinterest.ca/pin/331859066264206868/.

![]()

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or are being used under fair dealing for research purposes, private study, or education.